RESEARCH

YOUR BRITISH ANCESTORS - THE SMART WAY

I've never met anyone who regretted the decision to research their family tree, but I've met many who wish they hadn't started so late - in fact, I'm one of them!

The good news is that thanks to the far greater number of records that are now available online, it's possible for anyone whose ancestors are predominantly English to make amazing progress in a fortnight or less. In fact you'll probably make some interesting discoveries as soon as you put down this guide and start putting the tips into practice.

Note: itís a bit more difficult to research Welsh ancestors, even though the same records are available, simply because there are so many people with common surnames like Jones; if you have Scottish ancestors then some records are more readily available, but others are harder to access.

HERE'S THE CHALLENGEÖ.

Records from the last 100 years are generally harder to access - censuses are protected by the Census Act of 1920, and then there's the Data Protection Act to consider. Generally we don't get to see records unless there's a reasonable expectation that the people mentioned in them are deceased, hence the 100 year embargo.

So the challenge for YOU is to get back 100 years or more using the knowledge you already have, can glean from discussions with living relatives, or can discover by using the few online resources (such as indexes of births, marriages, and deaths) which do cover the last century. Once you're back to the 1911 Census it gets comparatively easy, because there are censuses every 10 years all the way back to 1841 - and with a bit of luck you'll soon be able to identify ancestors who were born in the late 1700s. Wowwwww!

START BY WRITING DOWN WHAT YOU ALREADY

KNOW

You might think you know nothing about your ancestors, but I'm not so sure. Most people hear family stories when they're growing up, and whilst some of those stories won't be completely accurate there will be snippets of information that come in very handy when you're trying to make sense of the information you find online - this is particularly likely if your ancestors had common surnames.

†

Tip: you can download a blank

Ancestor Chart from the LostCousins website when you

follow this link.

Print it out and fill it in as you go - itís for your use, so feel free to

scribble down anything that you think is important. You can transfer the

information to a family tree at a later stage.

I'm assuming that you know the names of your parents (including your mother's maiden name), and when they were born. You might even know where they were born, and when they married - assuming they did marry. These days a lot of people start families without getting married, but in 1946 just 6.6% of babies were born to an unmarried mother - so even if your parents didn't marry, the chances are your grandparents did.

Note: for the purposes of this

tutorial it's not about the moral and social issues, but the paper trail that

people leave behind. For every birth, marriage, and death there's an entry in a

register somewhere - and in a little while we're going to discover how to

pinpoint that information.

NEXT: TALK TO YOUR RELATIVES

If you've left it really late to start researching your family tree you might be the oldest in your family. But if not, now's the time to talk to older relatives who can provide you with snippets of information that will point you in the right direction. For example, they might know where your ancestors lived, or the surname of the man who married your grandmother's sister.

This sort of Information that might not seem obviously relevant, but believe me, it will be at some point! And it's not just older relatives who can provide useful information - when I started my research I asked around in the family and discovered that my younger sister had information that, unbeknown to me, she'd collected from our late aunt 20 years before.

Note: people weren't always known

by the name on their birth certificate; some were known by their middle name,

and some by a derivative of the forename, such as Nell or Nellie (instead of

Ellen), Polly (instead of Mary), or abbreviations such as Mike or Fred.

DIG OUT THOSE FAMILY MEMORABILIA

In most families there's an envelope, a tin, or a box which is full of things that might be needed one day. Or which nobody could bring themselves to throw away - and a good thing too, because now you're researching your family tree they're likely to prove invaluable to you!

When my father died a few years ago I found an envelope containing my mother's birth certificate, death certificate, and will (made just 10 days before she died), plus her mother's death certificate and her will (made 20 years earlier); a certificate from Manor Park Cemetery assigning a burial plot to my father's father; my father's mother's death certificate and her will - itemising furniture, crockery, and cutlery that she wanted him to have, some of which I can still remember from my childhood.

I wish I'd known that these documents existed while my father was still alive - there are many questions I would have asked him. As it was, there was nobody I could ask - but hopefully you won't leave it until too late.

INDEXES OF BIRTHS, MARRIAGES, AND DEATHS

All births, marriages, and deaths in England & Wales are recorded in registers held by the General Register Office, which is based in Southport. The GRO (as we're going to refer to the General Register Office from now on) gets its information from hundreds of local registration districts, each of which is divided into sub-districts with their own Register Offices. Registration districts can be confusingly named - for example, the district of West Derby is in the Liverpool area - and large towns and cities are often split into several districts. This article from the LostCousins newsletter will help you find the correct district starting with the name of the parish, though itís important to bear in mind that because most people rented their homes and had fewer possessions they moved around a lot more than we do, especially if they lived in urban areas.

The GRO produces national indexes of births, marriages, and deaths which are available for free public inspection at half a dozen libraries across England & Wales - but they're on microfiche, and indexed by quarter, so unless you know when to look it could take quite a time to find the right entry. (Until 2007 many researchers would spend days at the Family Records Centre in London looking up entries in the actual indexes - which were bound into enormous, and very heavy, leather bound books - family history was a less sedentary pastime in those days!)

,

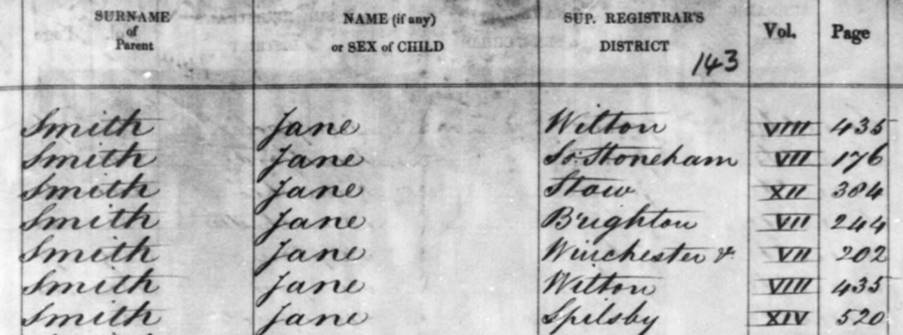

Part of the GRO birth indexes for

the first quarter of 1839

Fortunately, until 2008 the GRO used to sell microfiche copies of the indexes to anyone who was prepared to pay the price - and in the 1990s an enterprising charity called FreeBMD recruited volunteers to transcribe the indexes, commencing from July 1837 (when the registration of births, marriages, and deaths began in England & Wales), in order to create a searchable database of the index entries up to 1983, when the GRO started selling the information in a digital format. The FreeBMD project is still ongoing, but it's close to completion - most of the entries for the 1970s have now been transcribed.

Nowadays there are lots of websites where you can find indexes of births, marriages, and deaths for England & Wales which go all the way from 1837 to 2006 or 2007 (when the GRO stopped selling their indexes). I still use FreeBMD sometimes, but I generally find the Findmypast site quicker and easier.

Whilst Findmypast allows you to search for births, marriages, and deaths simultaneously, at this stage in your research you'll find it easier to search them one by one. These links will take you direct to the relevant search pages:

England & Wales Births 1837-2006

England & Wales Marriages 1837-2005

England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007

In November 2016 the GRO made available its own online indexes of births and deaths. These aren't simply copies of the indexes produced around the time of the event, but newly compiled indexes which include information not shown in the originals.

The new birth indexes cover the period from 1837-1917, whilst the new death indexes run from 1837 to 1957 - and even though they're more difficult to search, the fact that these new indexes sometimes include information that's not in the original indexes means that they could save you the cost of a certificate. They're particularly useful for births before September 1911 (as this is the first quarter when the mother's maiden name was included in the original indexes), and for deaths before 1866 (as until this year the index didn't include the age at death).

Tip: use Findmypast to find the

right entry, then look it up on the GRO website to see whether there's any

additional (or different) information.

When we research our family tree we usually work backwards in time, which means we'll typically encounter someone's death first, then their marriage(s), and finally their birth. There are usually clues to help us progress from one to the other, for example a death certificate will usually give the age at death or (since 1969) the precise date of birth, where known. This information isn't always 100% correct - people make mistakes, especially when they're grieving for a loved one - but it's usually a pretty good guide. The death certificate for a widow may give the name of her husband, making it easier to trace their marriage.

Similarly, when people marry they are required to give their ages and the names and occupations of their fathers. This information is quite often wrong in the 19th century (when no proof seems to have been required), and sometimes even in the 20th century, but nevertheless it provides a good starting point for the next stage of the search, which is to find your ancestor's birth.

Tip: ages on marriage

certificates are most likely to be wrong when there's a large gap in age

between the bride and groom; the father's name is most likely to be wrong when

it's exactly the same as that of the groom, especially

if the same occupation is shown.

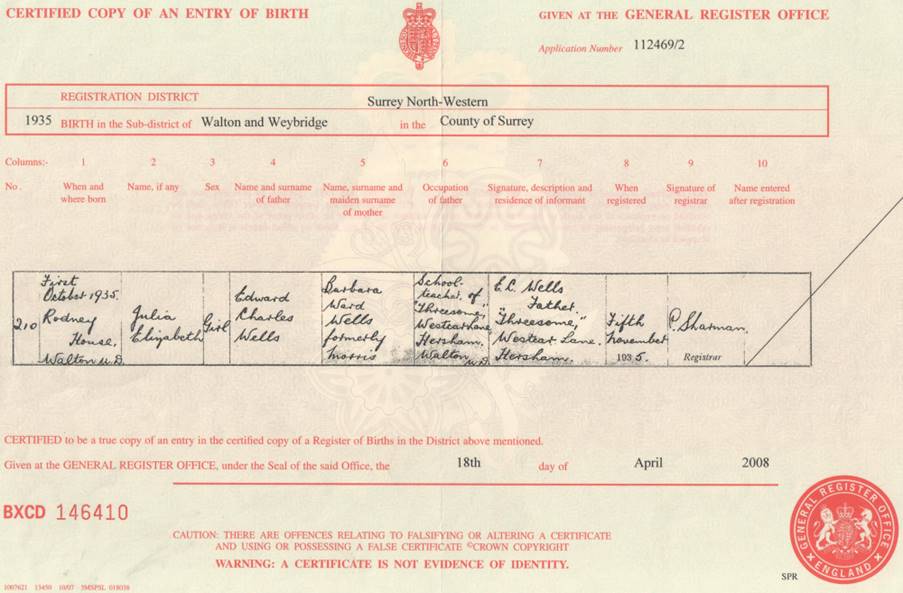

And when you find your ancestor's birth it will give the name of his or her mother - and hopefully the name and occupation of the father, too. Here's an example of a birth certificate:

That's the birth certificate for the actress Julie Andrews, star of Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music, and many other films and stage plays. According to her 2008 biography Edward (Ted) Wells wasn't her father, despite what the birth certificate says - nor indeed was Ted Andrews, her mother's second husband, whose surname she took.

Tip: you can ignore the reference

numbers on a certificate - the reference at the lower left is like the serial

number on a banknote, the one at the top right is the number of your

application, so equally meaningless (the only entry you might consider noting

is the number of the register entry, in this case 210). Also

the addresses shown often end, as this one does, in U.D. which is short for

Urban District, ie the council district.

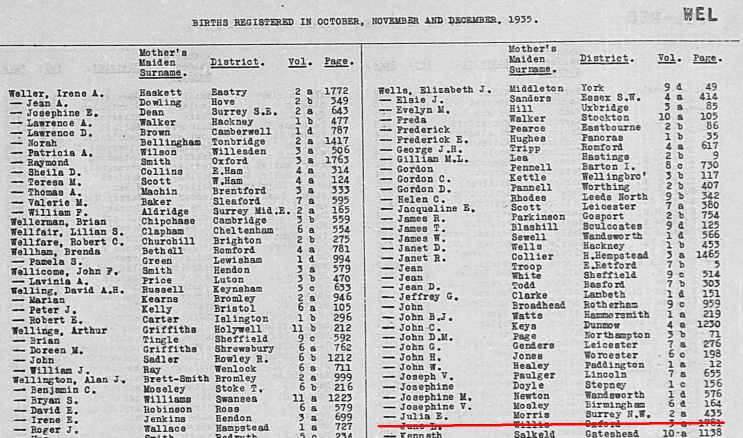

The index entry for that birth shows the following information:

As you can see, the index entry shows the child's forename (Julia), middle initial (E), and surname (Wells), as well as her mother's maiden name (Morris). As 42 days are allowed for the registration of a birth you can reasonably deduce that the birth date was between the middle of August and the end of December.

Note: all certificates are copies

(a certificate is a "certified copy" of a register entry), but if

you've inherited any handwritten certificates that were issued around the time

of the event they're a little bit special.

TIPS TO HELP YOU IDENTIFY THE RIGHT

INDEX ENTRIES

Let's suppose that you've found what you think is the right birth entry for your ancestor - is there any way you can be certain itís the right person? MaybeÖ.

Carry out a search for other children born to the same couple - even if the surname is a common one there probably wonít be that many other births where the mother's maiden name is also the same. If youíre using Findmypast you can sort the search results by birth year, and it will usually be obvious which ones relate to the same family (especially if they're all in the same registration district). Do any of the other names seem familiar - are any of them the names of your ancestor's brothers or sisters? Even if you don't know the names of your ancestor's siblings, perhaps you know that they came from a large family and, if so, does that fit with the number of entries you've found? Was your ancestor an only child, a twin, the eldest, the youngestÖ. any snippets of information you have can be checked against the entries you've found.

Note: sometimes there will be two

families in the same area where the surnames and maiden names are identical -

this will happen when two brothers marry two sisters. If you suspect that this

may be the case you can search for marriages between

people with those surnames to see whether your suspicions are correct.

Searching for other children born to the same couple also helps you find the right marriage - since the chances are that the first child was born after the marriage.†

IF YOU DECIDE TO ORDER CERTIFICATES

Sometimes you'll need to order a certificate to confirm that the index entry you've found is the right one, or to discover information that isn't shown in the index. They currently cost £9.25 each from the General Register Office - you can order them online, and they're typically despatched about a week later. (Currently the GRO are trialling a paperless system under which they provide an uncertificated copy of a birth or death register entry in a PDF file that you download from their site - but itís not an instant service, there's still a wait of about a week, but the cost is lower at £6.)

WARNING: there are websites that

will charge you much more for certificates - donít use them, only order from

the GRO. You'll find the official website here.

In general certificates issued by the local register office are more likely to be accurate, since the registers held by the GRO are copies, whereas the local register office has the originals - but before ordering certificates locally make sure they have the equipment to produce facsimiles of the register entries, otherwise all you will get is a handwritten, typed, or printed copy which could well be less accurate than a copy from the GRO.

Note: to order a certificate from

a local register office you first need to find out where the registers are

held, which isn't always easy given the reorganisations that have taken place

over the years. The local register office records are filed differently, so the

volume and page number references from the GRO indexes find the entry in their

registers won't help them - but knowing the year and quarter will.

HOW TO RESEARCH ON A SHOESTRING

Unless youíre very lucky, or have a lot of help, you're unlikely to get very far in your research without spending some money. And if you have to order certificates itís not just about the cost but the time you have to wait - it can be really frustrating! Fortunately you don't often need to buy a certificate - sometimes there's sufficient information in the indexes for you to be able to get to the next stage, and this blog post on the Findmypast site shows how easy it can be (however it's not so easy if the names, especially the surnames, are very common ones).

As mentioned earlier the birth, marriage, and death indexes up to the 1970s are available free at the FreeBMD website, and you can get limited free access to censuses at the FamilySearch website, though you'll need to register and log-in.

But the real goldmine when it comes to researching family in the 20th century is the 1939 National Register, which is exclusively available through the Findmypast website. Until recently this wasn't a budget-priced solution, because youíd have had to buy a 12 month subscription costing around £120 - but now you can get access to this valuable source for as little as £12.95, the cost of a 1 Month Plus subscription!

GETTING THE MOST OUT OF THE 1939

REGISTER

Drawn up in September 1939, soon after the outbreak of World War 2, the National Register was rather like a census (although because one of the key purposes was to issue identity cards people who already had official documentation weren't usually recorded). But whereas censuses are a snapshot on a particular day, the 1939 Register continued to be updated for the next half century, initially because identity cards continued to be used into the early 1950s, and then because the records were repurposed as the National Health Service Central Register.

How was the register updated? Strangely changes of address weren't noted, at least not in the part of the register that we get to see online - the main alterations relate to changes of name, sometimes to correct errors or omissions made in 1939, but most often they reflect marriages (and, increasingly, divorces). For example, here's the entry for my mother, who in 1939 was a 13 year-old schoolgirl who had been evacuated with her school to Suffolk:

![]()

Tip: the date shown on the left

isn't the date of my parents' marriage - it's a few weeks later - so I suspect it's

the date on which the change in name was notified to the authorities. When

youíre looking at historic documents always remember that they weren't created

for our benefit, but to fulfil some administrative purpose.

At Findmypast you can search the register using the surname that your relative was known by in 1939, or by a later surname. Indeed there are all sorts of different ways to search - for example, you can search by date of birth, or even by address (if you know it).

The 1939 Register doesn't show information about people who are, or might be, still alive so you won't find all of your family members, but - so long as you have English or Welsh ancestry - it will usually bridge the gap between what you and your living relatives know about your ancestors, and the information you need to find them in the censuses.

SEARCHING THE CENSUSES

Congratulations - if you're reading this article you must be back to 1911 (or earlier) on at least one of your family lines! Tracing your family between 1841 and 1911 is relatively easy because censuses provide all sorts of clues to help you identify your relatives.

For example, the censuses from 1851 onwards show the relationship between the head of the household (usually the father), and each of the other members of the household. This means it's far less likely that you'll pick the wrong household by mistake - and it also provides you with information that you can add to your tree.

Tip: sometimes the relationships

shown are wrong, but in an understandable way. For example, if the daughter of

the head of household has children, they may be shown as 'son' or 'daughter'

even though they're actually 'grandson' and

'grand-daughter'.

Censuses from 1851 onwards also show the place of birth of each person, making it easier to find their birth or baptism once you've found them on the census - it also makes it easier to find someone on the census if you know where they were born, perhaps from a later census.

Tip: people didnít always know

where they were born, but a mother always remembers where she was when she gave

birth; this means that birthplaces are most reliable on earlier censuses, when

children are still living at home.

All censuses show the occupation of each adult - a retired person might be shown as an 'annuitant'; someone who didnít work could also be shown as having 'independent means', although this doesnít necessarily mean that they were wealthy. This information usually helps us to track families from one census to the next, especially if the father's occupation is a skilled one, such as 'carpenter' or 'mason'.

But just because there's lots of information in the census doesn't mean that when you're faced with a search form you should aim to fill in as many boxes as possible - quite the reverse, in fact. It's usually best to start by entering just the name and age of the person you're looking for, and only adding a little extra detail if you get too many results.

Tip: don't assume that the

information on the census is going to be correct; you might know precisely when

your ancestor was born, but that doesn't mean that he got his age right when

filling in the census schedule. About half of the ages shown in the census are

wrong, and as you might expect it tends to be the ladies who knock off a few

yearsÖ.

Censuses were usually taken at the end of March or the beginning of April (although the 1841 Census was in June), and this means that for most people, their birthday would fall after census day. But by convention websites that allow you to search the census ignore this, and calculate the year of birth by subtracting the age shown on the census from the year of the census, thus someone shown as aged 20 on the 1881 Census will appear in search results as born 1861 even though the chances are that they were born in 1860 - assuming the age shown in the census is correct.

The names shown on censuses can vary - middle names tend not to be shown in full until 1911, and on the earlier censuses even middle initials are usually omitted (though middle names were, in any case, quite rare until the latter part of the 19th century).

DON'T RELY ON TRANSCRIPTIONS

Records are usually transcribed and indexed in order to make them easier to find, but because most records were handwritten the chances of errors are high. Not only is this something to bear in mind when searching for our ancestors, it's also important that when you find the record you look at the scanned image of the original document (if this is available).

If youíre using credits to do your research (rather than buying a subscription) itís very tempting to rely on the transcriptions, but ultimately it's a false economy since you'll want a copy of the original record for your files anyway.

Tip: sometimes the same record

can be found at more than one website, or in more than one record set at the

same website - so don't assume that there is no image available just because

the first record you look at isnít linked to an image.

NEWSPAPERS CAN PROVIDE UNEXPECTED CLUES

There are a lot of historic newspapers online at the British Newpaper Archive website (you can also access them with a World or Pro subscription to Findmypast); the collection is richest in the 19th century, but extends into the first half of the 20th century. Whatever the social status of your ancestors you could find them or their family mentioned: a report on a criminal case will usually mention not only the person(s) in the dock, but also the victims, witnesses, and police offices involved in solving the case.

Notices of births, engagements, and marriages tended to be limited to the middle classes, but newspaper reporting of deaths covered the whole social spectrum, especially if the death was violent or notable for some other reason. Reports of weddings and funerals often provide lists of attendees, usually giving the relationship between them and the deceased - this can be a very useful way to discover the married name of a female relatives. Obituaries can be a mixed blessing - whilst often rich in detail, they frequently include errors, sometimes quite important ones!

YOU MIGHT BE A BEGINNER, BUTÖ.

Don't assume that other people know more than you do. The Internet is awash with false or extremely dodgy family trees, and you would do well to ignore them. If you did look at someone else's tree the chances are you would make the same mistakes as them - if you research your ancestors independently you can minimise the chance errors simply by following a logical path.

Even when you think you've found the right person in the census, or the correct entry in the indexes of births, marriages, and deaths don't "close the case" until you've found information that confirms it in some way. For example, if itís a birth, look for other births to the same parents and consider whether they fit with what you know; similarly if it's a marriage, look for subsequent births. Sometimes you can even use the death indexes to confirm that you've found the right birth and marriage - because when a woman marries she normally takes her husband's surname, so the death index entry will be in one surname and the birth index entry in another. From 1969 onwards the precise date of birth is shown in the death indexes, and you can tie this back to the entry in the 1939 Register entry.

By the way, donít assume that if a website provides a 'hint' that the computer somehow knows something that you don't. Hints can be useful, but they can also be misleading. A hint is simply an extra avenue of investigation.

Tip: not everyone had a will, and

not all estates go to probate, but if you do find an ancestor in the probate

indexes it will usually give their precise date of death, their last address,

and - until the 1960s - the names of the executors (who might be family) - as

well as the value of the estate.

DON'T JUMP TO CONCLUSIONS

Even rare names can be common in certain parts of the country - don't assume that the first birth, baptism, marriage, or death that fits is the right one. Although piecing together your family tree is a bit like a jigsaw puzzle, there's no picture to guide you, and if put a piece in the wrong place it isn't going to be obvious that you've made a mistake - indeed you might never find out. Wishful thinking can cloud our judgement - always try to be as objective as possible. It's better to be too sceptical than too gullible - how awful it would be if you inadvertently spent your life tracing somebody else's ancestors!

MAPS HELP TO PUT THINGS IN PERSPECTIVE

Maps, especially historic maps from the time you're researching, are an essential aid. Few of us know the area where our ancestors grew up, so identifying the towns and villages where they lived - or might have lived - is very important. In the days before motorcars and railways most people's horizons were limited by the distance they could walk - so bear this in mind when looking at possible births, baptisms, and marriages. For many the only opportunity they would have had to meet people from outside their home village would have been on market day - assuming they had a reason to go to market. The National Library of Scotland website has historic Ordnance Survey maps for the whole of Britain - you'll find the maps for England & Wales here.

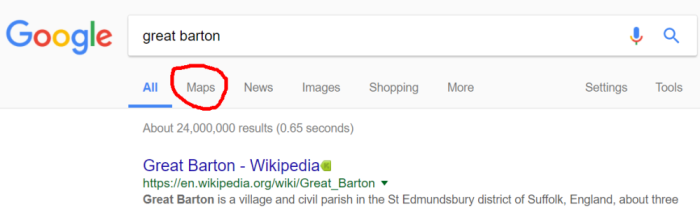

But modern maps also come in useful. You can use Google's Maps function to measure the distance between two locations - start by entering one place name in the usual Search box, then press Enter or click the magnifying glass symbol:

When you get the results, don't look at them, just click Maps (beneath the Search box) - here's part of what you'll see:

Finally click the circular icon above the word 'Directions' and enter the name of the other location as the starting point. Google Maps will automatically find a number of alternative routes between the two points - the shortest of these will be a reasonable guide to the distance that your ancestor would have travelled. Before the arrival of the railways it was unusual for people to go further than they could walk in a day - though when the work ran out locally they might travel any distance (miners are a good example); other exceptions are those who travelled as part of their work such as coachmen, tax collectors, or seafarers. Domestic servants in wealthy households might also be required to travel between a country estate and a house in town.

AS YOU GET FURTHER BACK

Parish registers are the main source of information prior to civil registration of births, marriages, and deaths - and whilst the registers for many counties are now online, for other parts of the country the most you might find online are transcribed records - which are better than none at all, but they rarely tell the whole story. Almost all surviving parish registers are held in county records offices, but they also hold many other records, some of which may never be made available online.†

Remember that around half the population was illiterate in the early 19th century, so census forms may well have been filled by the enumerator, not the head of household - and if this was the case he would have written down what he heard, not what the householder said. (Even in the 20th century some people didnít fill out their own census form - I was an enumerator for the 1971 Census, and can remember filling out the form for several old people living on their own.)

Middle names come and go - some people who did have middle names dropped them, others who weren't accorded a middle name on their birth certificate added one later in life. It can be particularly confusing for sons who were named after their father, who may have been known by as different name, perhaps their middle name, within the family.

But above all, remember that because a lot of people couldn't write they would have relied on their memory, rather than certificates or other records, and memories often play tricks!

Tip: surname spellings varied

enormously - even Shakespeare couldn't decide how to spell his surname - and

until the early 1800s you will find little consistency, even if the individuals

concerned were able to sign their own names (my great-great-great grandfather

married twice, but used different spellings of his surname). Even in the latter

half of the 19th century spellings continued to vary, especially between

different parts of the same extended family (the spelling of my grandmother's

surname changed between her birth and her marriage). So

the spelling of a name should never be a deciding factor - it's just one of

many things we need to take into consideration when we are weighing up the

different options.

RECORDING YOUR FAMILY TREE

At the start of this guide it was suggested that you could use the blank Ancestor Chart from the LostCousins website to make a note of the information you discover - sometimes writing things down on paper is best, particularly if you're trying to hold a conversation with an elderly relative. But before long you're going to want to store the information digitally - and when you do, you have two options. One is to use an online tree - these are usually free - and the other is to get a family tree program for your computer.

In fact, most experienced family historians have both - they keep their main tree on their own computer, but they also have an online tree (though usually it's a private tree, not one that any Tom, Dick or Harry can see). However when you're starting out it makes sense to begin with a free online tree, like the one at Findmypast.

Tip: most tree programs and

online trees are capable of importing and exporting

information in GEDCOM format, so transferring data from one tree program to

another is possible, and GEDCOM files are particularly useful when you want to

upload information from a tree program on your computer to an online tree.

DNA - IS IT THE FUTURE?

Our DNA comes from our ancestors - so will DNA testing replace records-based research?

The problem is, whilst we inherit all of our DNA from our ancestors, we don't inherit DNA from all of our ancestors. Worse than that, it's difficult to work out which segment of DNA came from which ancestor (you can only do it with the help of cousins), and there's certainly nothing in your DNA to tell you what the names of your ancestors were.

DNA is only useful to genealogists when it is utilised in conjunction with conventional research. Then it can be absolutely invaluable, helping you to bridge gaps in the written records (especially in cases of illegitimacy or adoption), and enabling you to verify that the research you've already done is correct.

It's important to maintain a balance between the time you spend investigating DNA matches - of which there could be many thousands - and the time spent on more conventional ways of connecting with other researchers who are your cousins (such as the LostCousins website). This is because the more documented cousins you have and the more records-based research you have carried out, the easier it will be to make sense of your DNA matches.