Newsletter – 11th

October 2022

1921 Census – the moment you’ve been

waiting for!

What you really need

to know about the 1921 Census

Putting the 1921

Census online - the inside story

Can you help with

this research project?

More British than the

English?

Mass burial site

discovered in Wales

SideView for Matches looks

promising

Don’t give a DNA test

for Christmas!

Was this really a

same sex marriage in 1708?

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 5th October) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February

2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

1921 Census – the moment you’ve been waiting

for!

Just

last week I was musing about when and whether the 1921 England & Wales Census

might become available on a subscription basis – and my dream has come true!

If

you have a Findmypast Pro subscription you can upgrade the remainder of your subscription

for the fixed price of £19.99, a sum that would barely buy a round of drinks

these days.

Earlier

there was a problem with the Findmypast website which meant that in some circumstances Pro subscribers were

quoted a higher price, but that seems to have been resolved.

For

those who don’t have a Findmypast subscription the good news is that from today

you can buy a 12 month Findmypast Premium subscription that includes the 1921

Census – at £199.99 it’s only £20 more expensive than a Pro subscription, which

makes it quite a bargain when you consider that a standalone subscription to the

1911 Census cost £59.99 in 2009 (or about £85 in today’s money).

In

those days an all access subscription to Findmypast cost £159.99 (well over £200

in real terms), but it didn’t include newspapers, any parish register images, Catholic

registers, the 1939 Register, or many of the other records that we now take for

granted – indeed, almost all of Findmypast’s overseas records have been added

since 2009. Even some of the ‘basic’ British records were missing: there were

no transcriptions of the Scottish censuses, or images of the 1881 England &

Wales census. We’re getting a great deal more in 2022, but paying less in real

terms.

If

you’re an existing Findmypast subscriber but have a Starter or Plus

subscription you can upgrade to a Premium subscription: how much this costs

will depend on which subscription you have now, and how long it has to run, but

there will be minimum charge of £19.99

IMPORTANT:

THE 1921 CENSUS IS NOT INCLUDED IN ANY 1 MONTH OR 3 MONTH

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Please

note that the prices I’ve quoted apply to Findmypast.co.uk – prices at Findmypast’s

other sites are roughly the same but in local currency (ie €23.99 in Ireland, $23.99 in the

US and $34.99 in Australia). Whether you are

upgrading or buying a new subscription PLEASE use the relevant link below (and

temporarily disable your adblocker, if you have one) so that you can support

LostCousins with your purchase. If asked about cookies click That’s fine

(you can always change the settings later if necessary) otherwise we probably

won’t get any commission.

What you really need to know about the 1921

Census

Back

in January I wrote an article which explained how to get the most out of the census

without spending a fortune. I’ve repeated it below, but please note that if you

have a subscription to the census there’s no need to follow the money-saving

tips, which were written at a time when you could only access the census on a

Pay-per-View basis.

·

Who's included? Not just the inhabitants of England &

Wales, but also those of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands; members of

the Armed Forces wherever in the world they were stationed, with the exception

of Scotland; Merchant Navy and fishing vessels that were either in port on

Census Night or returned in the few days following; visitors, tourists, and people

in transit.

·

Who's not included? Anyone who was not within the territory

on Census Night (except as noted above); many people who were homeless or had

no fixed abode; anyone who objected to the census and avoided being enumerated

·

Use the Advanced Search: I'm sure I don’t need

to tell LostCousins members this, but I've done it anyway!

·

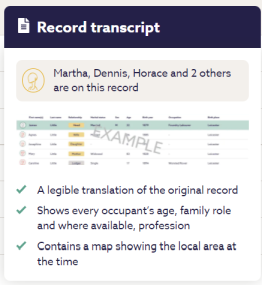

Transcripts: you shouldn't need

to view the transcripts, which will cost you an extra £2.50, since all the information

you need to know is either on the household schedule, or can be found by inspecting

the associated images (see the next article for more details).

Transcripts: you shouldn't need

to view the transcripts, which will cost you an extra £2.50, since all the information

you need to know is either on the household schedule, or can be found by inspecting

the associated images (see the next article for more details).

·

Before buying

an image:

you'll see a mini transcript (as shown on the right), but it will only give

three forenames at most, typically the person you searched for and two others;

it won’t tell you whether the people named have the same surname (in this case

I happen to know that they don't), nor will the head of household necessarily

be one of the people named (in this case he isn't).

·

Make sure you've

found the right household: they are lots of ways to search and you can narrow down

the number of search results by including extra information on the search form;

if you do purchase the wrong household, learn from your experience so that you don’t

make the same mistake again.

·

Census references: the piece number is handwritten on

the 'Cover' (it's preceded by the reference RG15) but is also part of the filename

when you download the image, and this is a much more reliable source; also on the

cover is the enumeration district; the other reference to record is the schedule

number, which is shown in the top right corner of a standard household schedule.

·

Addresses: the address of a household is on the 'Front'

of the form.

·

Large households: the standard form has room for 10 people;

there is a list of the different forms here;

households of up to 20 people should be available as a single unit, but I've

seen an example where due to poor handwriting the link has not been made.

·

Printing: the Print button on the image page doesn’t work

for me (though it works for my wife, who has a different make of printer), but

in any case I prefer to download images to my computer, save them, then adjust

them before printing; some of the inks used in 1921 have faded, so adjusting

the contrast and brightness will usually produce a clearer print (I use the free

Irfanview program which makes

adjustments to the image easy – and it has lots of other features, most of

which I never need to use).

The

image that bears the names of our ancestors and their family members may be the

most important part of the 1921 Census as far as we're concerned, but it's just

one side of the story. Indeed, it's just one side of the form – the back side.

The address, and most of the instructions to householders, are on the front

side of the form – whilst the form is just one of many that were bound into a

book with a stiff cover.

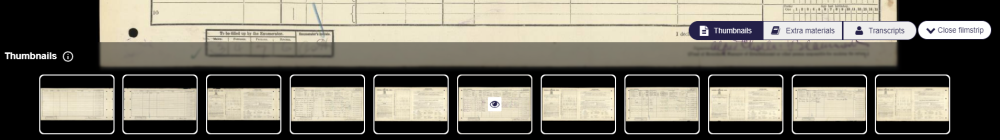

When

you first view the image of a household schedule you'll see that near the

bottom of the page there are thumbnail images of other schedules from the same enumeration

district:

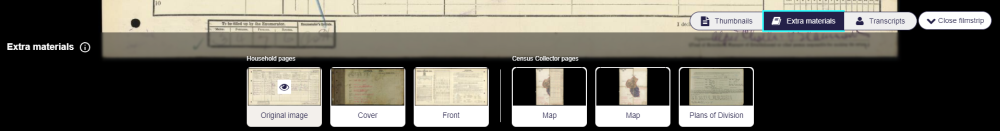

Unless

you have a subscription you can probably manage without seeing who was living

next door, but next to the highlighted Thumbnails tab you'll the words Extra

materials – clicking this will allow you to view other images that you have

already paid for, including the Front side of the household schedule,

and the Cover of the book:

What

you won’t find are the pages from the Enumerator’s Summary Book that we’re

familiar with from the 1911 England & Wales census – that’s because the Summary

Books were stored in the same building as the 1931 England & Wales census,

and were destroyed during World War Two. For more information see this article

from March in which I exclusively revealed the truth about what happened, based

on a letter held in The National Archives, but seemingly missed by other

researchers.

Putting the 1921 Census online - the inside

story

I

was delighted when Stephen Rigden, Records Development

Manager at Findmypast, agreed to write down the story of how the 1921

England & Wales Census was published online – not just because I can share

it with you, but also because it's a record that, sadly, we don't have for

earlier censuses. First published in my 10th January newsletter, it's

an article to read and then re-read, because it provides so much insight into

the process of digitising a census. Do feel free to share it with other family

historians using the link in the contents list at the top of this newsletter

(right click and choose 'Copy link'), but please don’t circulate copies – there

is no need, because this newsletter is online for everyone to read, as are all LostCousins

newsletters since February 2009. And now, over to Stephen….

IT IS A LONG TIME NOW since researchers in

England & Wales have been familiar with the experience of handling original

census returns. I started working as a professional genealogist in 1987 and

even then we used microfilm surrogates in the then Public Record Office at its Chancery

Lane and Portugal Street sites. Of course, there are countless advantages to

digitisation and online publication which none of us would wish to be without –

open access, endless search permutations, speed of research, instant download.

Using microfilms and browsing speculatively in the hope of finding a family of

interest could be quite dispiriting, as was queuing outside in the cold in

Portugal Street. What becomes harder to appreciate when one is accustomed to

the census online, though, is the physicality of a census as an archive collection.

The digitisation of a new census provides a rare opportunity for those involved

to get to know what a census is really like.

The first thing that strikes one is that the

1921 Census is huge. We all know that that must be true, given that it covers

an entire country and more, but it is another thing to see with one’s own eyes

the archive boxes containing more than 28,000 volumes of census material

arrayed on rolling stacks. The sheer size of the collection and the scale of

the task to digitise it are daunting. And in this case Findmypast was entrusted

with and responsible for the entire project from end to end – everything from

laying out and equipping the studio, the initial stocktake, the assessment,

preparation and conservation of documents, the imaging of every piece of paper

in every book in every box, and the post-imaging re-assembly – not to mention

catalogue metadata development, database creation, transcription, cleaning and

standardisation of data, search functionality etc. And all this under conditions

of security and confidentiality.

As readers will know, the 1921 Census was

closed for 100 years under the 1920 Census Act. All images and transcriptions

that we created had to be encrypted – effectively locked up and placed out of

reach until 50 days before release in January 2022. So, although we have been

actively working upon the project since January 2019, we couldn’t access the

material we had digitised until mid-October 2021.

Our work was undertaken on closed government

premises which required security clearance and the strict observance of

protocols – no mobiles, no smart watches or other devices with camera function;

no open windows; no straying from approved walkways within the building. This was

over and above the usual conservation and archive conditions that one would

expect – no food or drink in the studio, no pens, no jewellery except plain

wedding rings, no hand cream.

After the collection was digitised, it was

uplifted from its temporary location and conveyed under conditions of similarly

strict security to its place of permanent long-term storage. From that point

onwards, the physical census is effectively closed again in practice. For the

foreseeable future, then, access to the 1921 Census will only be through the

digital surrogate that Findmypast has created.

The time in the studio was therefore a

wonderful and privileged opportunity to get to know a census inside out. No one

will ever know the 1921 Census as deeply and as intimately as those conservation

team members who worked on this project for so many months. And those of us who

were present during the closing phases of the digitisation project in September

and October 2021 will be the last persons to have that hands-on experience of

the 1921 Census.

So what was it like?

Even when you’ve opened hundreds of the bound volumes, there is still an

excitement in untying and opening a fresh box and discovering what is inside.

Usually, you would find two volumes of approximately equal thickness, but

sometimes just one fat one, or even three or four slimmer books if the pieces

covered sparsely populated areas or shipping. Each piece is a big landscape

volume with tough hard covers front and back, into which the hole-punched census

schedules had been bound. Originally, the volumes had been belted shut with an

integral strap which was bolted to the rear cover board. At some point before

our involvement, broken and damaged belts had been replaced with new straps.

Both types of strap bore a nice Stationery Office ink stamp. The original belts

were left on if still in good condition, but our instructions were to cut them

off cleanly and replace them with archival unbleached cotton tying tape if not.

So what was it like?

Even when you’ve opened hundreds of the bound volumes, there is still an

excitement in untying and opening a fresh box and discovering what is inside.

Usually, you would find two volumes of approximately equal thickness, but

sometimes just one fat one, or even three or four slimmer books if the pieces

covered sparsely populated areas or shipping. Each piece is a big landscape

volume with tough hard covers front and back, into which the hole-punched census

schedules had been bound. Originally, the volumes had been belted shut with an

integral strap which was bolted to the rear cover board. At some point before

our involvement, broken and damaged belts had been replaced with new straps.

Both types of strap bore a nice Stationery Office ink stamp. The original belts

were left on if still in good condition, but our instructions were to cut them

off cleanly and replace them with archival unbleached cotton tying tape if not.

When you untie the belt strap, or unknot the

tape, and open the book, it stretches well over a metre and occupies a good

part of the width of your workbench. The census schedules themselves had been

laced into the covers, using the four holes punched in 1921 along the left-hand

edge, and we had to cut these ties to release the individual schedules for processing.

The fronts of the schedules contain the address panel, printed instructions and

worked examples. The backs of the forms show the household information that

every researcher most wants to see – details of household members – with the

householder’s signature towards the bottom-right and the schedule number

inserted by the enumerator in the top-right. The schedules were bound into the

volumes with their backs uppermost. This means that when you open a volume and

turn the protective acid-free paper insert, you see immediately the details of

the first household.

Turning over the schedules page by page, you

start to follow the enumerator’s walk and visualise how the census was taken back

in the summer of 1921. Each volume has its own integrity – it enumerates a very

precise and closely defined geographical area. A subsidiary part of the 1921

Census collection contains the so-called Plans of Division (TNA’s archive

series RG 114) which carved up the country into manageable units and, among

other things, described each enumeration district in detail. The Census Office

knew what it was doing with a very high degree of accuracy and certainty.

You start to see patterns too. Patterns of

employment, for example. Page after page show the same or similar occupations,

or the same industry, or the same employer. The pattern of farm labour is

revealed to you. On previous censuses, you would see agricultural labourers,

horsemen and others but without a sense of how they belonged together in the

economic landscape. Suddenly, in 1921, you see how they are working for a

particular local farmer, whose name appears time and time again.

The Census Office was very interested in

employment in 1921, and in particular in the distances people were travelling

to work (this is why workplace was requested on the form). I wasn’t entirely

sure of the benefits to family historians at first, but it quickly becomes

apparent that all sorts of possibilities are opened up by the 1921 Census capturing

details of employment. Firstly, of course, as a genealogist you now know who

your ag lab ancestor worked for and where, or in whose factory your great

grandfather worked his lathe. But you can also find his or her workmates. Local

historians can now see this information and reconstruct a workforce. You could,

if you wish, find all the labourers in a steelworks, or all the ticket

inspectors on the municipal tramway. This was simply not possible with the 1911

or earlier censuses.

When you work with the census as an archive

collection, what you see is context. You see things you wouldn’t see online

because your online search experience is so targeted – with a little luck,

online you should be able to go straight to the person of interest to you. What

this does, for most of us, is limit our experience of the census to our own

families and the specific archival pieces that interest us. It is slightly

better for professional researchers who investigate families other than their

own, and thereby gain a broader understanding, but even their experience amounts

to little more than a glimpse. Working on the digitisation of the 1921 Census

exposes you to all sorts of things you would otherwise have been unaware of –

the variety of different forms (for different places and different types of

sizes of household), for example, or the various returns for institutions such

as asylums, hospitals and workhouses. I’m very keen on browse experiences on

genealogy websites, where you are able to open a volume and then page through

the images from start to finish.

There is a separate browse experience for the

1921 Census available from launch. However, as access is initially pay-per-view

only, take-up of this is likely to be low except in locations such as The National

Archives or the National Library of Wales reading rooms, which are blessed with

free onsite access. In the fullness of time, though, when 1921 Census enters

subscriptions, I’d recommend that all serious family historians take the time

to browse

through at least one entire piece, from cover to cover, even if it is merely

one for your local area. It will take you an hour and probably more but there’s

really nothing like it for developing a deeper understanding of the census as

an archive record. And the good thing about doing that online is that you won’t

end up with the lingering smell of the 1921 Census in your hair and on your

clothes, and your fingertips darkened with the century’s worth of dirt and dust

that has accumulated in the physical volumes!

The 1921 Census is the last for 30 years, due

to the accidental destruction by fire of the 1931 and the lack of a 1941 census

being taken in wartime. As far as anyone knows at this juncture, the 1951

Census will not be opened until 2052. I’d therefore encourage all family

historians with roots in England & Wales, or the Isle of Man or the Channel

Islands, to make the most of the 1921 Census, as it is likely to be the last

family history event of national significance for some time. It really is hard

to think of anything that could eclipse it.

Stephen Rigden, Records Development Manager,

Findmypast

Thank

you, Stephen, not just for the incredible effort and expertise that you put

into the project, but also for taking the time to set down your story – not in

ink that will inevitably fade, on paper that will eventually deteriorate, but

in a digital format that will preserve it for centuries to come. Thank you too

for the suggestion to browse the 1921 Census – now that I have a subscription I’m

going to do just that!

Around

the time this article was first published Dave Annal, a professional

genealogist who spent over a decade working for The National Archives, wrote a

wonderfully insightful blog post focusing primarily on how the censuses were

accessed in the days before the Internet made life so much simpler – you’ll find

it here.

Can

you help with this research project?

In

the past hundreds of LostCousins members have assisted Professor Rebecca

Probert of the University of Exeter with her researches into marriage, bigamy,

and related issues. Now it’s the turn of one of her colleagues to ask for your

help.

My

name is Dr Rachel Pimm-Smith, and I am a lecturer in law at the University of

Exeter. I am conducting a study about the boarding-out regime under the poor

law between its inception in 1870 and the first world war. I am looking for records of first-hand

information to provide insight into the lived experiences of children who participated

in the first public foster care system in England. The results from this study

will be published in an open-access article in the Journal for Legal History.

They will also appear in my forthcoming book about the history of child

protection in England.

- Do you have a family member who

was sent to a foster family outside their parish between 1870-1914?

- Was the foster home organised by

the poor law guardians (as compared to a charity like the Waifs and Strays

Society or Barnardo’s)?

- Do you have any written records

(letters, diaries, memoirs etc) that discuss their memories or

experiences?

If

you can answer YES to all three questions, I’d love to hear from you!

Email:

dr.rps.research@gmail.com

In

the last issue I reported

changes in the law in Ireland that will make it easier for adult adoptees to

find out their true identities, but have you ever wondered what the success

rate is for adoptees and others who try to identify one or both parents using

DNA?

The

answer was revealed last week in a paper co-authored by five experts in genetic

genealogy – all of whom are, I believe, LostCousins members. It’s the first

research to focus on Britain and Ireland – an earlier survey was dominated by

respondents from the US, because at the time Ancestry had only just begun to

offer their test in other countries.

Reading

the paper I discovered some interesting statistics that I don’t recall seeing before:

one was an estimate by Ancestry for the number of people in the UK who had

taken a genealogical DNA test up to April 2019 – it was 4.7 million, about 1 in

11 of the adult population. Another was an estimate of the number of children

fathered in Britain by American GIs during World War Two – around 22,000.

It’s

well worth reading the paper, and if you think the success ratio of around 50%

is low, bear in mind that few of the subjects would have had previous experience

of family history research – after all, it’s hard to get started when you don’t

know who your parents were!

How

successful is commercial DNA testing in resolving British & Irish cases of

unknown parentage?

was published in The Journal of Genealogy and Family History and is

available in PDF format. It’s free to download – you’ll find it here.

In

common parlance the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ is often used in a way that implies that

true-blooded Englishmen are descended from the Anglo-Saxons; after all, the very

name of our country derives from ‘Angle’.

Yet

the Angles and Saxons were Germanic tribes who settled on the island of Britain

in the 5th and 6th centuries – if that makes us English

then I’m a Dutchman. And perhaps I am, because many of my ancestors came from

the east of England: research recently reported

in New Scientist found that people buried in the east of England in the

7th century could trace 76 per cent of their ancestry to recent

migration from Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands.

It’s

no wonder that so-called ethnicity estimates are so often at odds with what we

know about our ancestry – our family trees are based on records, that – if we’re

lucky – go back 500 years. And whilst we get all of our DNA from our ancestors,

we haven’t inherited DNA from all of our ancestors – once you get more than 10

generations back our genetic tree begins to look nothing like our genealogical tree.

Note:

it’s rather like what we see when we trace the branches of our tree, our collateral

lines – many of them die out, but we’re obviously descended from the lines that

didn’t die out, otherwise we wouldn’t be here today. But it does raise an

interesting question – are the ancestors who didn’t contribute to our DNA

essential to our existence? I’ll leave you to ponder that – and if you do have

any thoughts or comments on any of the issues raised in this article, please don’t

write to me, post them here

on the LostCousins Forum where everyone can see them.

The

research on which the New Scientist article is based was published in Nature

and is open access – if you want to delve into the detail, you’ll find it here. Note that

the abbreviation ‘aDNA’ stands for ‘ancient DNA’, and should not be confused

with ‘atDNA’, which is the abbreviation for ‘autosomal DNA’. I found one sentence

particularly interesting:

“…most present-day Scottish, Welsh and Irish

genomes can be modelled as receiving most or all of their ancestry from the

British Bronze or Iron Age reference groups, with little or no continental

contribution.”

More

British than the English?

Mass burial site discovered in Wales

The

remains of more than 240 people, including children, have been unearthed by

archaeologists working on the remnants of a medieval priory found beneath a

former department store in Wales. Believed to be the site of a medieval priory,

the remains include men who died in battle – but around half of those buried were

children.

You

can read more in this article

posted on the BBC News site this morning.

SideView for Matches looks promising

In

the last issue I wrote very briefly about Ancestry’s latest DNA feature, Sideview

for Matches – at the time of writing the article this exciting new feature had

been withdrawn because of teething issues, though beta testing resumed shortly

afterwards, and most readers who have tested with Ancestry DNA now have access.

Having now had several days to evaluate this new feature, I’ve discovered just

how invaluable it is going to be!

When

we test our DNA we’re presented with thousands of clues to the identity of our

ancestors, clues that come in the form of matches with mostly distant cousins. Because

of the way that Ancestry integrates two enormous databases – their bank of DNA results

and their collection of family trees – they’re able to tell us how we’re

related to some of our matches with a high degree of reliability. ThruLines

and Common Ancestors are not perfect because they are dependent on

family trees which are not perfect, but they work well, especially the latter.

We

can build on those foundations using Shared Matches, to identify the

part of our tree – though not usually the precise line – in which we’ll find

our connection to some of our other cousins. However we’re still left with many

thousands of matches that are unused – they are clues, but clues to what?

The

strategies in my DNA

Masterclass will identify hundreds of matches that are worth a closer look,

either because our cousins have ancestors in their tree with the same surname

as our ancestors, or because they have ancestors from the same town or village.

These are the matches most likely to help us knock down our ‘brick walls’, but

we’re still left with thousands more matches with cousins who don’t have family

trees, or have large gaps in their trees, or whose trees don’t contain any information

that obviously matches our own tree.

SideView

for Matches provides a helping hand, by dividing most of our matches into Maternal

and Paternal. Don’t expect the algorithm to get it right every time, but my experience

to date suggests that it gets it right well over 90% of the time. Ironically it’s

your closest matches that might look strange – whilst they won’t be assigned to

the wrong side of your tree, you may find that they are shown as ‘Both sides’

or ‘Unassigned’. That’s because we share so many segments of DNA with our

closest relatives that the chance of one or two of those segments being incorrectly

labelled by the SideView algorithm is fairly high.

The

one circumstance in which it might appear that a close match has been wrongly

assigned is when Parent 1 and Parent 2 have been incorrectly identified – not by

the algorithm, but by the user. If you remember, we first encountered SideView

when Ancestry split our ethnicity estimate between our parents – and given how

flaky ethnicity estimates are, some users will inevitably have been misled. I

had a hunch which way round my parents were, but I certainly wasn’t convinced

enough to share my guess with Ancestry. As it happened my hunch was correct –

but it might not have been. Even now I have not identified Parent 1 and Parent

2 (though I obviously know which is which) because this would make it more difficult

for me to assess how well SideView for Matches is working.

There’s

a little information about the way SideView works on the page that is displayed

when you click the new menu item (‘By parent BETA’), but the best source of information

I’ve found so far is this post

on the blog of Leah Larkin, one of the most respected gurus of genetic

genealogy.

If

you manage multiple DNA tests please remember that the labels Parent 1 and

Parent 2 are chosen at random. As it happens, for both myself and my brother

Parent 1 is our mother – but that’s just coincidence.

All

autosomal DNA tests use similar technology, so you might think it wouldn’t matter

which test you take – I’m well-known for my moneysaving tips, so you might

expect me to recommend one of the cheaper tests on the market.

And

yet I don’t – because my long experience of working with DNA has taught me that

being able to access the world’s biggest database of genealogical DNA tests is far

more important than price alone. Only by taking Ancestry’s own test can you get

into their database of more than 23 million tests – because, whilst you can

transfer your Ancestry results to other providers, you can’t upload results from

other providers to Ancestry.

The

other feature that sets Ancestry apart from other sites is the way that they integrate

DNA with family trees – they’ve done this far more than any other site, which

not only makes it easier for you and me, it saves us an enormous amount of time

and effort.

Please

use the relevant link below so that you have a chance of supporting LostCousins

when you make your purchase (if you’re not taken to the offer page first time,

log-out from your Ancestry account then click the link again).

Ancestry.co.uk

(UK only) – REDUCED FROM £79 to £59

Ancestry.com.au

(Australia and New Zealand only) – REDUCED FROM $129 to $89

Ancestry.ca

(Canada only) – REDUCED FROM $129 to $79

Ancestry.com

(US only) – REDUCED TO $59

Tip:

make sure you follow the advice in my DNA Masterclass – doing what comes

naturally won’t work nearly as well, as I explained

recently.

Don’t give a DNA test at Christmas!

Ancestry

generally quote 6-8 weeks from receipt of a sample before the results are

available online, and you might have to wait even longer for some of the features

such as ThruLines and SideView to update.

But

in my experience the actual waiting time is more likely to be 3 or 4 weeks, provided

you don’t send the sample off at a time of peak demand – such as in the days

and weeks after Christmas.

So

if you decide to give a DNA test as a Christmas present, find a way of giving it

to your friend or relative ahead of the festive season, and explain to them why

you’ve done this. If they can get their results back before Christmas then so

much the better, as it’ll be something they can share with their extended family!

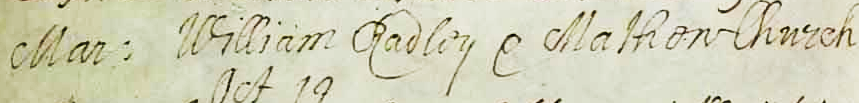

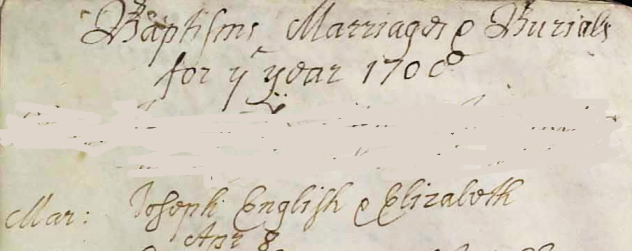

Was this really a same sex marriage in 1708?

Just

7 miles east from the home of LostCousins, the parish church of St John &

St Giles at Great Easton is of Norman origins, though built on the site of a

Saxon structure, and the quantity of Roman bricks and tiles used in the construction

hints at an even longer history.

It

was there on 19th October 1708, that according to the parish

register, William Radley married Mathew Church – and there can be no doubt

about what is written:

All

Rights Reserved. Reproduced by courtesy of

the Essex Record Office D/P 232/1/1 (digital image 59)

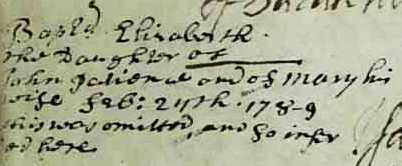

However

when something doesn’t seem right it’s a good idea to investigate how reliable the

source is. You don’t have to go far to see that errors have been made, for

example near the top of the same page is a marriage where the surname of the

bride isn’t stated:

All

Rights Reserved. Reproduced by courtesy of

the Essex Record Office D/P 232/1/1

And

also on the same page is a baptism entry that had been omitted completely, and

added later in a different hand:

All

Rights Reserved. Reproduced by courtesy of

the Essex Record Office D/P 232/1/1

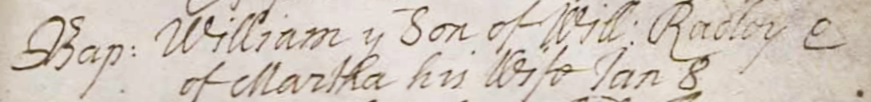

Someone

who has made two errors could well have made a third (or more – I haven’t

attempted to verify the other entries, these are just the ones that stood). And

on the facing page we can see who William Radley really married – his wife’s

name is correctly recorded in the baptism entry for their first child:

All

Rights Reserved. Reproduced by courtesy of

the Essex Record Office D/P 232/1/1

As

Lady Bracknell might have said, to mess up one register entry may be regarded

as a misfortune, to mess up two entries looks like carelessness, but to make three

errors on one page is carelessness of the highest order. (The cleric might

perhaps submit in mitigation that the name Martha Church was so close to ‘Mother

Church’ that he got confused.)

It’s

important to remember that even ‘primary sources’ have errors and omissions.

Vicars did not complete the register at the time – they relied on their own

notes, the sexton’s notebook, and sometimes on their memories.

I’d

like to thank John Young, Vice Chair of the Essex Society for Family History

for pointing out the ‘same sex’ marriage, and Essex Record Office for allowing

me to reproduce the images. By the way, Essex was the first county to put full colour

scans of parish registers online, way back in 2008 – before either Ancestry or

Findmypast had any parish register images.

It’s getting cold, so

my wife has been in the garden gathering the remainder of the harvest and

moving delicate plants into our small greenhouse. I’ve just taken a photo of what

she has gathered this week – including more than enough chillies to last us

until next year!

It’s getting cold, so

my wife has been in the garden gathering the remainder of the harvest and

moving delicate plants into our small greenhouse. I’ve just taken a photo of what

she has gathered this week – including more than enough chillies to last us

until next year!

Half

a century ago, in the days before Britain’s High Streets were overwhelmed with coffee

shops, cafes, and bars I used to visit an establishment called Planters

in Cranbrook Road, Ilford on a Saturday afternoon – not only did they have a

sizeable restaurant at the back, they sold leaf tea and coffee beans in the

little shop at the front.

Those

of you who also grew up in the Ilford area will recognise this photo

of Cranbrook Road – Planters is somewhere in the distance on the

right-hand side. Wests (in the foreground) is where my mother bought

patterns and many of the fabrics she used – I don’t know that she ever wore a

dress that she hadn’t made herself.

The

coffee beans I bought in those days were Kenya Peaberry – I loved the flavour,

and was over the moon to discover recently that I could buy them online. I started

buying the coffee ready-ground (most suppliers will grind it to order and ship

it in a vacuum pack), but a few months ago I mistakenly ordered beans and,

since I no longer have the brass and wood hand grinder that I used in the 70s,

I decided to splash out on an electric grinder. As usual I headed over to the Which?

website – Which? magazine is published by the Consumers’ Association, a

charity founded in 1957 to protect the interests of consumers, so it’s a trustworthy

independent source.

Even

though price is not a factor in their reviews, it’s not always the case that the

most expensive products get the best ratings – and in this case the grinder that

came top of the list with an ‘Excellent’ rating for everything other than noise

was this model, currently on sale for

£44.99, which is fractionally less than I paid in June, and less than a quarter

of the price of the grinder that came second. I soon found the perfect settings

– which for me was 5 cups and a coarse grind. I use a stainless steel 1 litre

vacuum-insulated cafetiere (this one),

which makes coffee that tastes even better than I remember from the Cona

coffee maker I was given for my 21st birthday in 1971. It’s an awful

lot easier, too!

I’ve

continued buying beans because the flavour and aroma of the coffee is so much

better when the beans are freshly ground. I know that the fashion is to buy

bean-to-cup coffee machines, but they’re jolly expensive, take up more space,

and are harder to clean. Each day I weigh out 36g of coffee beans (cost about

61p including shipping), and my wife and I get three large mugs of delicious coffee

between us – better than any coffee I’ve tasted since the 1970s.

How

do I weigh the coffee beans? I put the grinder on our electronic kitchen scales

with the lid removed, press the zero button on the scales, then keep pouring

until the reading shows 36g (or thereabouts). It’s so easy, I wish I’d switched

back to Kenya Peaberry years ago – it’s extravagant, of course, but as

extravagances go it’s definitely on the cheap side.

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

I’m off now to search the 1921 Census – my first challenge is to

find my grandfather’s work colleagues at Towler & Son in Stratford, as some

of them are in a photograph that I inherited.

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2022 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!