Newsletter – 18th

October 2021

Tying the knot EXCLUSIVE

Census secrets

EXCLUSIVE

Tracking Holmes ancestors using DNA

How to become a professional genealogist: from aggro

to AGRA

Toad in the Hole – is our rich culinary heritage

being forgotten?

Gardeners' Corner: Heading into winter

with exotic plants

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 7th October) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February

2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

Tying the knot EXCLUSIVE

In June last year I

published an appeal by Professor Rebecca Probert, the leading academic

authority on the history of marriage law in England and Wales; if you contributed

to the project you'll be particularly interested in this update from the Professor:

"A huge thank

you to all those who replied to my call for information about ancestors who

married in a civil ceremony or who were Catholics or Nonconformists. In total,

I received responses from 184 family historians about 1,132 marriages

celebrated between 1837 and 2017. All information was then entered into a

dataset to help identify trends – so whether you contributed one example or

hundreds, it all contributed to building up a picture of how people married!

"The results

will shortly be appearing in an article in the Journal of Genealogy and Family

History – together with a number of case studies provided by family historians

to illustrate particular trends. This is an online open access journal so will

be available free of charge (I will send the link as soon as it is published).

I also have further articles planned as it was not possible to do justice to

the richness of the data in a single piece.

"Everyone who

contributed an example also gets a thank-you in my new book, Tying the Knot: The

Formation of Marriage 1836-2020, which has just been published by Cambridge University

Press. This traces how the law developed over that time, and the changes in the

way that people married. I’ll be talking about it at an event organised by the Society of Genealogists on 6th November and

at an online seminar on 3rd December (further details to follow – follow me at

@ProfProbert or watch this space!)."

Professor

Probert's books are some of the most well-thumbed on my shelves – her

ground-breaking work, Marriage Law for

Genealogists took a highly complex topic and made

it understandable, and the follow-up Divorced, Bigamist,

Bereaved? built on that foundation to provide further

insight into our ancestors' behaviour (and misbehaviour). In researching her

latest book she discovered even more about marriage

law and practice after 1837, and she'll be sharing the key points with

attendees during the Zoom talk on 6th November.

She has also written,

contributed to, or edited numerous academic works, as well as a book about the

life of a soldier's wife during the Peninsular War of 1808-14. Please follow the

appropriate link below to find out more:

Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.ca Amazon.com.au

Newspaper

reports are usually the most readily-accessible records of inquests but as this

article

on the National Archives website explains, records of inquests over hundreds of

years have survived. There's also a link to an interesting podcast

by Kathy Chater, in which she explains how inquests not

only tell us how people died, but can also provide insight into how they lived.

Most

modern records that have survived are held locally: they are usually kept by

the coroner's office for 15 years and then transferred to the local record

office; whilst they are closed to the public for 75 years, next of kin should

be able to obtain access. For example, Patricia in New Zealand told me recently

that she was able to get a copy of the records of the 1995 inquest into the

death of her mother, who sadly died in a road traffic accident on the Isle of

Wight.

There

is a very interesting section about inquests in England & Wales on the

website of the Crown Prosecution Service – you'll find it here. Note in particular

that the fact that a post mortem is carried out

doesn’t necessarily mean that there will be an inquest – it depends what the post

mortem has revealed.

Post mortem reports from St

George's Hospital in London from 1841-1920 are online here should you have good

eyesight and a strong stomach – and want to understand how Victorian post

mortems compare with modern TV portrayals such as Silent Witness.

By my calculations there are more than 25,000 cases but you can browse them by

categories such as murder and suicide; if you follow this link you'll be able to

find out how James Bond met his maker in

1896.

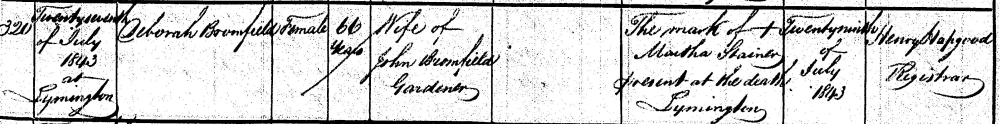

Death

certificates normally show the cause of death, but this example from the early

years of civil registration is a rare exception:

These

days we can be fairly confident that, allergies aside,

the food we buy isn't going to poison us – but in earlier centuries careless or

unscrupulous merchants were able to get away with murder. The website Artisan

Food Law is primarily aimed at small producers who want to stay on the right

side of the law (all of them. hopefully), but it also includes a chronology

of food law and related incidents that begins in 1266 and will be of

interest to many family historians. For example, in 1861 it was claimed that

"that 87% of bread and 74% of milk sold in London was adulterated",

and in 1900 in "the north of England 6,000 people [were] affected, seventy

died, when beer [was] found to be contaminated with arsenic [in] sulphuric acid

used in the preparation of sugar supplied to brewers."

Tip:

if, like me, you've not only enjoyed but also made real sourdough bread you'll

find this blog post

interesting.

In the last issue I wrote

that the enumerators' summary books "are our only source of information up

to 1901", but that was a slight simplification, as Dr Donald Davis

reminded me this week. Some years ago Dr Davis discovered that some of the

household schedules from the 1841 Census of Shropshire had survived in the county

record office, and he wrote about his findings in the May 2013 issue of The Local Historian, which you'll

find here

(all issues of this excellent journal from 1952 onwards are currently free to

download, with the exception of the most recent issue).

Those of us who started your research before Ancestry

and Findmypast made the England & Wales censuses available online remember

that the microfilms of the enumerators' summary books included pages that we

don't see online. In his latest email Dr Davis pointed out that there can be

nuggets of information hidden away on those pages:

In 1841 the

enumerator was requested to fill up the following three tables:

(1) The number of

persons who, on the night of 6 June slept:

a)

in barges, boats, or

other small vessels remaining stationary in canals or other inland navigable waters;

b)

in mines or pits;

c)

in barns or sheds;

d)

in tents or in the

open air; or

e)

those who for any

other cause, although within the District, have not

been enumerated as inmates of any dwelling house.

(2) If any temporary

influx of persons into the District, or temporary

departure of persons from it shall have caused considerable increase or

decrease of the Population of the District the enumerator was requested to

state the numbers of males and females so affected and the supposed cause and

the kind of persons involved.

(3) The number of

Persons known to have emigrated from the District to the Colonies or to foreign

countries since December 31, 1840. Many Enumerators ignored the Tables, many

wrote nil to confirm that there were no persons affected. Others entered the

numbers as requested. Still others could not resist entering the actual names

of people.

It is a shame that this data is not included

in the commercial census sites. A presentation I gave at Family Tree Live

looked at one county, Devon, to summarise the primary evidence recorded by its

enumerators in the three tables. There were 366 enumerators in that county who

did not leave the three tables entirely blank. Many recorded nil. This is

useful to the local historian. Occasionally the enumerator named names which

would be of great interest to the family historian. The prize for thoroughness

goes to enumerator John Wills Jr. in the parish of St. Thomas the Apostle who recorded the

names and ages of those who slept on vessels on 6 June 1841. He even named the

vessels on which they slept.

Dr Davis has kindly allowed me to share with you

the spreadsheet he compiled for Devon; even if you don’t have ancestors from

that glorious county it’s well worth a look to get a

sense of the sort of information that can be found. You can download the spreadsheet

in Excel format by clicking this link.

In

the 19th century many children died before reaching the age of 5 – there were

no vaccinations against the diseases of childhood – and in 1841 life expectancy

at birth for a boy was low, just 40 years. However, that doesn’t mean that men

were lucky to live beyond the age of 40 – a boy who survived to the age of 5 had,

on average around 50 more years of life to look forward to, while a man aged 50

had a good chance of living to the age of 70.

This

page

at the Office for National Statistics website has a number of charts relating

to life expectancy – the figures I've quoted are taken from the second chart,

and you can see how the shape of the curve has changed over time. For a detailed

statistical guide to life expectancy in the 21st century in the UK download the

spreadsheet that you will find here

– insurance companies use tables like these for calculating life assurance premiums

and annuity rates, but there are good reasons for individuals to make use of

them when planning their finances, although it's important to remember that they

are averages, not predictions..

Following the articles in the last newsletter there

seemed to be foundlings everywhere I looked - my wife and I watched an episode

of The Repair Shop last week in which a member of the public who was a foundling brought

her teddy bear in for repair – it was her only connection to her birth mother. Then

there was an episode of Our Lives subtitled Finding My Family which told the story of Leah, a foundling who hit the headlines in

1994 when she was discovered in a hospital toilet (it's on BBC iPlayer here). And LostCousins

member John told me about a foundling baptised in St Stithians,

Cornwall in July 1804 as Julia Stythians; when she

emigrated with her husband to Australia in 1848-49 she

was recorded in the passenger list as July (foundling).

And finally, the news I'd been waiting for – the release

date of Nathan Dylan Goodwin's new book, The Foundlings. It'll be out on 30th October and my review will appear in the next

issue of this newsletter, but if you want to place your order now, please

follow the relevant link below so that you can support LostCousins:

Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.ca Amazon.com.au

This week I was looking at a discussion in the Who Do You Think You Are? Facebook group when I noticed a comment about a marriage in 1784 which

suggested that 25 was rather old for a woman to be marrying for the first time.

It's a common misconception that people married young in earlier centuries – research

published by Wrigley and Schofield in 1981 (and re-published in Marriage Law for Genealogists – see above) shows that in the second half of the 18th century the average

age at which women married for the first time was 24.9 years. Another source I

found quoted 26.

Although boys of 14 and girls of 12 could marry

until 1929, economic reality and parental discretion served to limit the number

of youngsters who married. A further factor was that apprentices could not

marry without the permission of their master, and soldiers needed the permission

of their commanding officer if they wanted the marriage to be recognised (which

is why you will sometimes come across a couple who married each other twice).

Hopefully one day somebody will carry out systematic

research into the ages shown on marriage certificates after the commencement of

civil registration (1837 in England & Wales). My experience suggests that in

the 19th century at least half of the ages shown (or implied) were wrong, and

that if anything they're even less reliable as a source than ages shown in the

census – but it would be good to back up this hunch with research.

One of my 8 great-great grandmothers was named Sarah Holmes, so I'd

been hoping that one day I'd find that I was descended from a Sherlock Holmes –

but he hasn't shown up in my researches thus far. Mind you, tracking the Holmes line has

involved a fair amount of detective work (see the next article), so I like to think

of myself as a spiritual descendant of the fictional detective.

One of my 8 great-great grandmothers was named Sarah Holmes, so I'd

been hoping that one day I'd find that I was descended from a Sherlock Holmes –

but he hasn't shown up in my researches thus far. Mind you, tracking the Holmes line has

involved a fair amount of detective work (see the next article), so I like to think

of myself as a spiritual descendant of the fictional detective.

The name Sherlock Holmes doesn't appear in the

England & Wales birth registers until 1897, a decade after the first

Sherlock Holmes story – A Study in Scarlet – was published, and 4 years after Holmes had apparently died at the

Reichenbach Falls, although there was a Harry Sherlock Holmes whose birth was

registered in 1894. In the books Sherlock had an older brother, Mycroft, who

sprang to prominence only in the 21st century, in the series featuring Benedict

Cumberbatch as Holmes: the first – and only – Mycroft Holmes birth was registered

in 1901, but intriguingly there was a Harry Mycroft Holmes born in 1891.

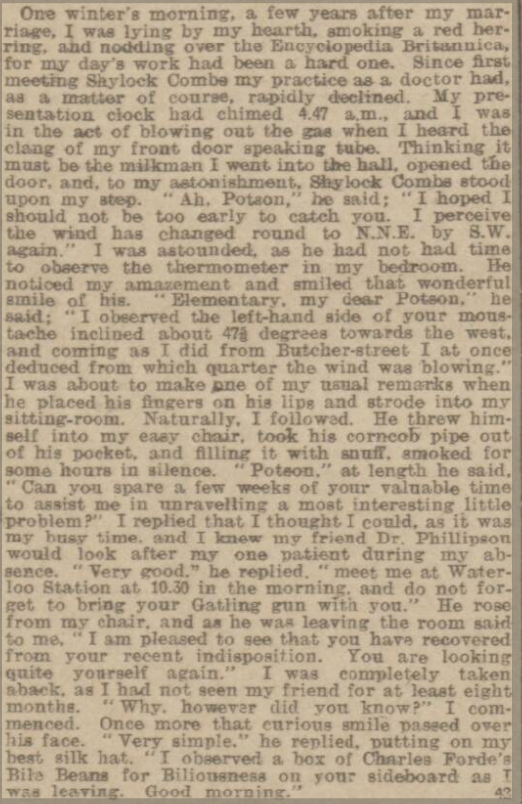

Having killed Sherlock Holmes off in order to focus attention on his other writings, of which The Lost World is probably the most

notable, Arthur Conan Doyle eventually relented and wrote his third Sherlock Holmes

novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles, which was serialised in The Strand Magazine between August 1901 and April 1902. Nevertheless this didn’t stop the Northampton Mercury from

publishing the spoof on the right in their 15th November 1901 issue .

(Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS

RESERVED. Used by permission of Findmypast)

Two years later Doyle published a short story, The Adventure of the Empty House, in which it was revealed that Holmes had faked his death at the Reichenbach

Falls in order to evade his enemies. Many more short

stories were to follow – the last was published in 1927.

Although we often refer to him as Conan Doyle, Conan

was one of his forenames, not part of his surname (though it was the surname of

his godfather). There was a time when double-barrelled surnames were the province

of the aristocracy, but gradually the aspiring middle-classes laid claim to this

style of address. Nowadays they are more likely to result from women retaining

their maiden surname after marriage, in the American style, though often it's

just an indication that the parents of a child weren't married to each other.

Doyle was not just the author of some of our

best-loved works of fiction; he qualified and practised as a doctor. In his

spare time he was a sportsman of some note, playing

soccer for Portsmouth (he was their goalkeeper), and playing 10 matches for the

MCC (Marylebone Cricket Club). As a bowler he took just one first-class wicket

during his career, but it was that of WG Grace, the most famous batsman of the

era.

But it's as a writer of detective stories that Arthur

Ignatius Conan Doyle is mostly remembered – they certainly had quite an impact

on me when I read them nearly 60 years ago, and I still follow the example of

the famous detective, who said "When you have eliminated all which is

impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth."

Mind you, Sherlock Holmes couldn’t call on DNA to

help him – thankfully we can…..

Tracking Holmes ancestors using DNA

My great-great-great grandparents, John Holmes and Hannah

Read, married in 1827 at St Dunstan, Stepney, east London (not to be confused

with St Dunstan's in the East which, confusingly, was further west). For a long

time I had pencilled in an 1804 baptism for John to

Edward Holmes and his wife Charlotte, but I was unable to prove to my own

satisfaction that this was the right baptism – London was, after all, the most

populous city in the world at the time, and many of the inhabitants had

migrated to London from other parts of the land.

There were a number of

Ancestry trees that showed John's parents as Edward and Charlotte, but they also

showed the couple marrying more than 200 miles away in Plymouth. Since most of

the population of England lived within 200 miles of London it seemed likely that

there would be many other couples who would fit as well – after all, Holmes isn't

exactly a rare surname (there were over 178,000 Holmes births registered in

England & Wales between 1837-2006). Some of these people were DNA matches

of mine but that didn’t provide a link to Plymouth, and some of them showed

Edward as born in Yorkshire, though without offering any justification for this

choice.

The breakthrough came when I spotted a DNA match

with a cousin in Australia who was descended from an Isaac Holmes, who had been

tried at the Old Bailey in 1818 for stealing a pair of pantaloons value 30

shillings (about a month's wages in those days) and sentenced to 7 years' transportation

– he was only 18 years old. Most surviving records give no indication of where

Isaac was born, or who his parents were, but the Certificate of Freedom issued in

1830 shows that he came from Plymouth. This fitted perfectly with this baptism on

10th February 1800 at Stoke Damerel – then in Devonport,

now part of Plymouth – to Edward & Charlotte Holmes:

Image © Copyright. Plymouth Archives; used by kind

permission of Findmypast

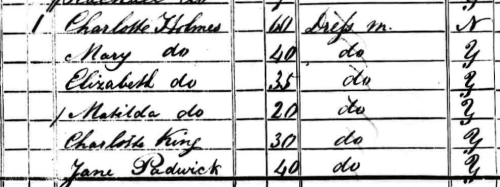

A daughter, Mary Ann, who was born in 1797 had been

baptised on the same day, and this fitted with 1841 Census which showed

Charlotte, by then a widow, living in St George in the East with four of her

daughters (the younger Charlotte also widowed, the rest still single):

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of

The National Archives, London, England. Used with the permission of Findmypast

(Although

all four daughters are shown as born in Middlesex in fact only two of them were.)

Another

daughter, Sarah, had registered Edward's death just a few months earlier. From

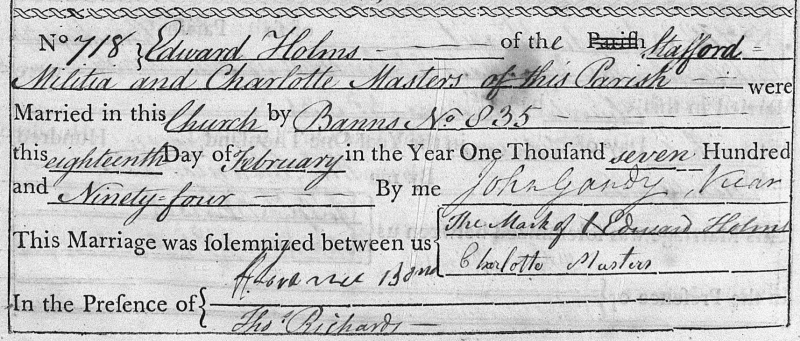

the 1851 Census it was apparent that Charlotte and Sarah had been born in Boston,

Lincolnshire and the register not only confirms that their father was a

bricklayer (as shown when my ancestor John and his older sister Elizabeth were

baptised in 1804), it also gives their mother's maiden name as Masters. This

tallies with this 1794 marriage at St Andrew, Plymouth:

Image © Copyright. Plymouth Archives; used by kind

permission of Findmypast

Note

that Edward is conveniently shown in the marriage register as being with the

Stafford(shire) Militia, which had been embodied (called-up) at the start of the

Napoleonic Wars and marched down to Plymouth in 1793. The following year they

were stationed at Weymouth, Dorset where they caught the eye of King George III,

who holidayed there – this ultimately led to the regiment being posted to

Windsor in June 1798, which might explain how Edward and his family ended up in

London – though since he was a bricklayer by trade the fast-growing city would have

been a likely destination anyway.

This

is yet another example where DNA evidence has proved important to my research –

it enabled me to confidently connect together records

from London, Plymouth in Devon, Boston in Lincolnshire, and Australia. I've not

only been able to confirm that Edward & Charlotte were my 4G grandparents, I've found their marriage and been able to identify Charlotte's

parents, her paternal grandparents, and her grandmother's parents.

Considering

how well DNA has worked out for so many family historians it surprises me that

there are still a significant minority of experienced researchers who aren’t prepared

to make use of such a valuable tool – or at least take a DNA test so that the

information they've inherited is preserved for the benefit of future

generations. Documents and photographs can be scanned, memories can be written

down or recorded - but when it comes to DNA the only way to preserve it is to

take a sample and send it to a laboratory. No matter how many children we have there

will be sections of our DNA that none of them have inherited – and even those

sections that have been inherited by the children will be jumbled up with the

DNA of their other parent.

So if you want to help the family historians of the future,

testing your DNA is "Elementary, my dear Watson" – as Sherlock Holmes

almost, but never quite, said.

How

to become a professional genealogist: from aggro to AGRA

Most

LostCousins members have been researching their family history for 20 years or

more, and I suspect more than a few of you have wondered whether you could capitalise

on all that experience by transforming your hobby into a source of income.

On

Saturday 30th October the Society of Genealogists are hosting an online talk by

Antony Marr, a LostCousins member (and a police officer for 30 years), who retrained

as a professional genealogist and is now Chairman of the Association of

Genealogists and Researchers in Archives (AGRA), one of the leading

professional bodies in the UK. During his career he has also acted as a Deputy

Registrar and if I remember rightly, we first met when we both attended a

meeting at the Home Office organised by the General Register Office.

The

Zoom talk starts at 10.30am and runs until 1pm, including questions. If you do

decide to become a professional genealogist the course fee of £20 (£16 for SoG members) will be tax-deductible, as will many of your

other expenses. To book or find out more please follow this link

– and don’t delay, because events mentioned in this newsletter tend to sell out

very quickly!

Toad

in the Hole – is our rich culinary heritage being forgotten?

According

to this BBC article

nearly 1 in 5 Britons don't believe that 'Toad in the Hole' is a real dish, and

a similar number don't believe 'Spotted Dick' exists. Even 'Bangers and Mash' is

considered fictional by 11%.

It's

certainly true that many of the dishes that were the mainstays of my diet as a

child don't find their way onto my plate these days, but that's only because I know

(and care) more about nutrition now than I did then. I do still eat 'Liver and

Bacon', which was one of my favourites as a child, and if fish wasn't so

expensive 'Cod in Parsley Sauce' would be on the menu more often.

Which

of your childhood favourites do you still enjoy? Post your comments on the

LostCousins Forum so that other members can read them (please don’t send them

to me as I'm busy helping members solve the mysteries in their trees).

Tip:

if you’re taking part in the LostCousins project to connect cousins around the

world you may already have qualified to join the forum – and even if you

haven't, it won't take long to put that right. To find out where you currently

stand check your My Summary page.

Spelling

wasn't something most of our ancestors worried about, and not just because many

of them were illiterate – until the Victorian era even educated people cared

little for spelling, if they thought about it at all. Even

Shakespeare, considered by many to be the greatest writer in the English

language wrote his name in many different ways (none

of which was 'William Shakespeare', by the way).

Spelling

variations multiply when there are different accents involved, and this beautifully-told story is a

wonderful example of the challenges that family historians face. Well worth a

read!

Gardeners' Corner: Heading into winter with

exotic plants

Now

that autumn has arrived in the northern hemisphere, and winter is just around

the corner, my attention has turned to the exotic plants that won’t survive an

English winter. Once again my article is a little too

long for the newsletter, so Peter has allocated me a page of my own, which

you'll find here.

Tip:

if you're in New Zealand you’re just coming out of your winter,

but read the article now so that you don't make the same mistake that I

did!

I

hope you enjoy the latest article. If you have any questions or comments please send them to Peter (at the address in the

email which told you about this newsletter) and he'll pass them on to me.

Thanks,

Siân

PS

here are some current offers from a supplier I've used in the past….

20%

off Herbs (ends 27/10/21)

15%

off Pots & Containers (ends 20/10/21)

3

for 2 Autumn-planting bulbs (ends 27/10/21)

Plant

clearance – save up to 40% (ends 20/10/21)

As

anticipated I got my booster jab on Saturday 9th October,

and I was delighted to find that I could have a flu jab at the same time. In

England over-65s generally get a slightly different flu

vaccine from younger people, one that has an extra ingredient designed to boost

the immune response (I imagine it's the same in other parts of the UK). Until

last year I'd never had a flu jab – it has been many, many years since I last

caught flu, because working from home (as I have since 1997) dramatically reduces

my exposure to infectious diseases – but now I'm a lot older and a little

wiser.

Countries

around the world are changing their strategies for dealing with the pandemic. The

New Zealand government had been pursuing a Zero-COVID strategy, but that seems

unsustainable now that the Delta variant has reached the shores of the island

nation – this article

from Wired sums up the situation quite well. There has been a similar

change of tack in Australia – see this BBC article.

In

the past week there have been two revelations about COVID tests – the first is

that research has shown lateral flow tests to be more useful than previously

thought; the second was the discovery that around 43,000 PCR tests processed by

a single commercial laboratory in the UK in September and October are thought

to have given false negative results. It will be some time before we are able

to gauge the impact of this apparent systematic failure, but it could be substantial

– it will almost certainly have cost lives. Ironically, when the story began to

break it seemed at first that the large number of negative PCR tests following

positive lateral flow tests indicated a problem with the latter.

The

latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (released on Friday) show

that over 8% of Year 7 to Year 11 pupils would currently test positive for

COVID:

|

Modelled percentage of the population testing

positive for COVID-19 by age/school year, England |

||||||

|

6 October 2021 |

|

|

|

|||

|

Grouped age |

Modelled % testing positive for COVID-19 |

95% Lower credible Interval |

95% Upper credible Interval |

Modelled ratio of people testing positive for

COVID-19 |

95% Lower credible Interval |

95% Upper credible Interval |

|

Age 2 to School Year 6 |

3.13 |

2.66 |

3.64 |

1 in 30 |

1 in 40 |

1 in 25 |

|

School Year 7 to School Year 11 |

8.10 |

7.31 |

8.90 |

1 in 10 |

1 in 15 |

1 in 10 |

|

School Year 12 to Age 24 |

1.05 |

0.78 |

1.39 |

1 in 95 |

1 in 130 |

1 in 70 |

|

Age 25 to Age 34 |

0.63 |

0.47 |

0.84 |

1 in 160 |

1 in 210 |

1 in 120 |

|

Age 35 to Age 49 |

1.23 |

1.07 |

1.41 |

1 in 80 |

1 in 95 |

1 in 70 |

|

Age 50 to Age 69 |

0.80 |

0.70 |

0.90 |

1 in 130 |

1 in 140 |

1 in 110 |

|

Age 70+ |

0.64 |

0.53 |

0.77 |

1 in 160 |

1 in 190 |

1 in 130 |

|

Source: Office for National Statistics –

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey |

||||||

These

statistics are for people in the community – they don’t include people in hospitals,

care homes, or other communal establishments. Vaccines are our main weapon for

fighting off the virus, but according to this Guardian article

only 14.2% of 12-15 year-olds in England have been vaccinated, whereas the

figure for Scotland is 44.3%. What on earth is going wrong? The roll-out of

booster jabs in England is also disappointingly slow – see this BBC News article published just as

I was finalising this newsletter.

Although

a lot of people who were previously working from home are now returning to

their offices for part of the week, it seems that office days aren't spread

evenly over the working week. This Evening Standard article

suggests that Wednesday and Thursday are the busiest days based on data

collected by the mobile phone company O2 from its masts in the City of London –

the picture might be somewhat different for other parts of London, and other

cities, but I suspect it won’t be that different. It's good to know that many employers

are still allowing their employees to work from home full-time or part-time,

and I suspect that some are wondering why they didn't embrace flexible working

before they were forced to.

For

me flexible working has always been important – when I was in the software publishing

business in the 1980s and early 90s most of my developers worked from home,

whether they were coding or designing graphics. For example, the 1988 soccer

game pictured in the last issue was a collaboration between developers working

many miles apart, some of whom never met each other. You might be wondering how

we managed this before the Internet – at first we

relied on the post, but then modems got faster and we were able to send files around

the country (and, indeed, the world) over standard telephone lines. The transmission

rates were slow by today's standards, however the

files were a lot smaller than they are today.

If

you live in the UK you will probably have noticed that

most mobile phone companies have ended free roaming in the EU – but not O2 and

not GiffGaff, the mobile provider that I've been

using and recommending for many years (GiffGaff is owned

by O2 and uses their network, but offers much more competitive deals). There's

no commitment – you buy a 'goody bag' that lasts for a month but at the end of

that month you can upgrade, downgrade or simply not renew.

All of the goody bags include unlimited phone calls

and texts. What varies is the data allowance – at times of the year when I'm

going to be at home most of the time I choose the £6 goody bag, which includes

500MB of data – plenty for web-browsing and navigation, but not enough for

streaming. But if I'm going to be staying away from home

I might choose the £10 or £15 Golden goody bag, which come with 10GB and 25GB of

data respectively, more than enough for me to send out emails to the 70,000

readers of this newsletter while I'm travelling (and with the larger goody bag

I can watch TV as well). You can get a free GiffGaff

SIM by following this link, and we'll

both benefit from a £5 bonus if you decide to activate the SIM.

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2021 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter

without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional

circumstances. However,

you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for

permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins

instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE? To

link to a specific article right-click on the article name in the contents list

at the top of the newsletter.