Newsletter – 15th

November 2023

GRO add 70 years of deaths to Online View

BREAKING NEWS

Were workhouses places of comfort?

Women and the crime of bigamy FREE PRESENTATION

More civil registration errors

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 9th November) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February

2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

GRO add 70 years of deaths to Online View BREAKING

NEWS

There

was some great news from the General Register Office today – from 9am this

morning it became possible to view England & Wales death register entries

from 1837 all the way up to 1957, which is the last year for which the registers

have been scanned and digitized. Previously you could have paid £7 for a PDF of the entry - and waited nearly a week to get it -

so the new service offers an effective saving of 65%.

Although birth register entries from 1837-1922

have been available since the public launch of the Online View service in July,

death register entries from 1837-1887 were the only ones available at launch

(and this was also the case during the private beta, which I was fortunate to

be involved in from September 2021 onwards).

What

does this mean for family historians? Those of you who have used the service

since July will know that being able to access images instantly (the only delay

is the time it takes to pay) and cheaply (each register entry costs just £2.50)

transforms the way we work. For a detailed explanation of how to use the Online

View service see the Special

Edition newsletter which I published shortly after the July launch – it tells

you things that even the copious notes on the GRO’s own site omit!

My

ancestor Robert Jeffreys Roper, father of my illegitimate great-grandmother

Emily Buxton, came from a Suffolk family where they reused family names, both

surnames and forenames. For example, his middle name (Jeffreys) was also his

paternal grandmother’s maiden name, and one of his elder brothers was Thomas

Peck Roper, Peck being their mother’s maiden name. The eldest brother was called

Edney, an unusual name which seems to have been adapted from Edna (a name I’ve

come across in my research, but have yet to connect to

my tree).

My

ancestor’s eldest sister was christened Theoda, also a very rare forename – so it’s

reasonable to assume that their mother, Mary Ann Peck, was descended from Samuel

Peck and his wife Theoda Steagall. However there is no

record that I can find of that couple (or any other Peck family) having a

daughter baptised as Mary Ann around the right time, and whilst Samuel and

Theoda did have a daughter named Mary, I can’t rule out the possibility that

she died as an infant.

These

days children are more likely to be named after celebrities than ancestors – or

named on a whim, if the parent is a celebrity. This article

from the Guardian looks at naming trends on both sides of the Atlantic.

Were workhouses places of comfort?

Nobody

familiar with the novels of Charles Dickens would want their ancestors to have entered

the workhouse, but archaeologists working on the site of the St Pancras

workhouse, built in 1809, have found evidence that the workhouse was originally

intended to provide a more welcoming environment than the one that Dickens

describes. This article

describes the findings so far.

Women and the crime of bigamy FREE

PRESENTATION

At

5.15pm (London time) next Tuesday, 21st November, Professor Rebecca

Probert will be giving the Annual Lecture at the prestigious Centre for English

Legal History, part of Cambridge University.

Entitled

Women and the Crime of Bigamy in English Law, 1603-2023 the presentation

it is likely to be of great interest to family historians with English or Welsh

ancestry, and whilst I can’t be in Cambridge because of other commitments I will

be attending via Zoom – and so can you. The talk is free whether you attend in

person or online – please follow this link

to book.

Tip:

laws aren’t only relevant to those of us who have law-breakers

in our tree – the law of the land as it was, or as it was perceived to be, will

have influenced all of our ancestors in the decisions they made.

Although

crime passionnel might sound like a romantically-named culinary concoction, it’s more a case of

someone who helps themselves getting their just desserts….

In

August 1917 Anton Baumberg, who went by the name “Count

de Borch”, was shot dead at a boarding house in Porchester Place – just to the north

of London’s Hyde Park. He had 10 bullet wounds, according to one newspaper

account, though according to another newspaper only 4 bullets were fired – but there

was no doubt who had fired the fatal shots, it was Lieutenant Douglas Malcolm,

the husband of the woman with whom Baumberg had been

having an intimate relationship. Some said the fictitious count was a white slave

trader, others thought he might have been a German spy – but everyone seemed to

agree that he was a bounder, and when Malcolm was tried for murder the following

month the jury acquitted him, in what was dubbed the first crime passionnel in the English legal system.

The

sordid story was of great interest to the popular newspapers of the time, but it

might have been long forgotten had not Lieutenant Malcolm been the father of the

highly-respected film critic Derek Malcolm, who died this July at the age of 91

– you can read his obituary here.

Or, to be more precise, Derek Malcolm grew up

believing that Douglas was his father, only to be told the truth by an aunt after

Douglas Malcolm’s death in 1969.

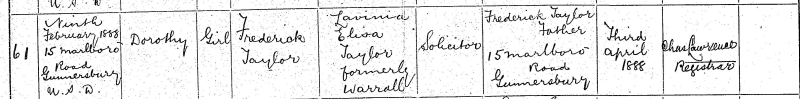

What

interested me about this story was not the lurid detail, but the cavalier way

in which Dorothy Malcolm (neé Taylor) changed her

name and her age as she sailed through life. She was born plain Dorothy Taylor on

9th February 1888 at Gunnersbury, west London – she was the second

child, and eldest daughter of Frederick Taylor, a solicitor, and his wife

Lavinia Elisa Warrall:

By

the time of the 1911 Census Dorothy had lost her father, but gained a middle

name and a fancy spelling of her first name – she was no longer plain Dorothy,

but Dorothie Vera:

©

The National Archives – All Rights Reserved. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

Clearly

this change of name was approved, or at least accepted, by her mother – who had

completed and signed the census form. At least Dorothie’s age was shown

correctly – she was 23.

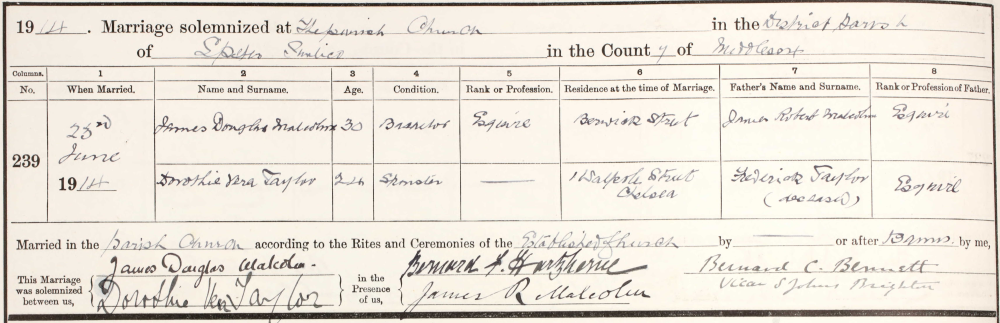

Three

years later, when Dorothie married James Douglas Malcolm at St Peter’s in

Pimlico, her age had advanced by only one year; she was now 24. Her late

father, formerly a solicitor, had been promoted to ‘Esquire’:

The

happy couple hadn’t been married long before Douglas Malcolm headed off to war,

leaving his young bride behind. By the time of the 1921 Census a lot had

happened, but you wouldn’t know that from the census schedule:

© The National Archives – All Rights Reserved. Used by kind

permission of Findmypast

After

7 years of marriage and 4 years of war Dorothie had apparently aged by just 3

years – she was, in fact, 33 years and 4 months old on Census Day (I imagine

she was the one who amended the census schedule, carefully obscuring whatever

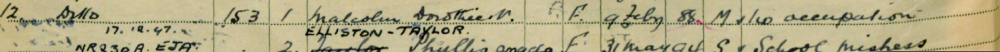

her husband had written). But when the National Register was compiled in September 1939

the question on the form was different – people were asked for their date of

birth rather than their age, and for once Dorothie gave the correct information,

as you can see:

© The National Archives – All Rights Reserved. Used by kind

permission of Findmypast

Mind

you, had she continued to knock 6 years off her age she would have been the

same age as her younger sister Phyllis, who was living with her in 1939.

Phyllis,

a spinster school mistress had also changed her name by 1939 – the unusual

middle name Bert, presumably a family surname, had been dropped and replaced by

the more gentle-womanly Angela. After the war Phyllis also upgraded her surname,

becoming Elliston-Taylor, which must have sounded far more grand – and this

fiction seems to have been perpetuated when in Debrett’s People of Today

(2006) Dorothie’s maiden name was incorrectly recorded as Elliston-Taylor (see Wikipedia).

In reality Elliston was the first name of their

maternal grandfather, Elliston Warrall, who married

Lavinia Victoria Street in 1858.

It

took me a long time to establish what was truth and what was fiction in this

case study – and I wasn’t even trying to solve the murder! One most unexpected

outcome of my research was the discovery that in 1911 Dorothie and her family

were living in Goodmayes, where I grew up – the other,

equally unexpected, was the sober realisation that there is only a thin

dividing line between a crime of passion and a so-called honour killing.

Last

month I recounted

the true story of Tony and Jane (not their real names), and the impact on their

lives of an impostor who went through a marriage ceremony using a false identity.

If you didn’t read the story at the time it’s well

worth reading before you read this follow-up article (and even if you did it’s

probably worth refreshing your memory).

Jane

married Bruce – at least, that’s what she thought, but not long after their

marriage it became clear that Bruce wasn’t who he claimed to be, and to this

day nobody knows who he really was. Acting on advice from people whose

judgment she respected, Jane treated the marriage as null and void, eventually

getting together with Tony a few years later and marrying him. However she hadn’t told Tony the full story – after all, she’d

been advised to forget about the whole sorry episode - and Tony, being a gentleman,

hadn’t liked to pry. And as I wrote last month, ”many

years later, a mystified Tony, by now a widower in his eighties, discovered

that despite the circumstances, Jane's marriage to an unidentified man was not

null and void, and that he himself had been the counterparty to a bigamous

marriage. Even worse, it must surely mean that their children were

illegitimate….”

Here’s

what Professor Probert had to say:

Tony

himself would not be regarded as a bigamist, even if Jane was. And their

children would be deemed to be legitimate by virtue of the Legitimacy Act 1959 –

this provided that the children of a void marriage were to be treated as

legitimate if at least one of the parents had 'reasonably believed' the

marriage to be valid.

It's

also possible that Jane was not a bigamist either – for example if the man

pretending to be 'Bruce' was already married to someone else. In that case

Jane's first marriage would have been void and her second valid.

Even

if her first marriage was valid, it's very likely that a court would have

acquitted her of bigamy had the case ever come to trial – by this time the

courts had held that a genuine belief as to the invalidity of the first marriage

would be a good defence to a charge of bigamy.

I

wondered whether Jane could have applied to the court for the marriage to Bruce

to be annulled, and if not whether Jane could get a quiet divorce behind closed

doors. Again Professor Probert knew the answers:

She

would not have been able to have the marriage annulled - the category of

'mistake' is very narrowly defined in English law.

In

terms of divorce, she would (eventually) have been able to petition on the basis of 5 years' separation without any of the

details coming out. Petitioning on the basis that he had behaved in a way that

she could not reasonably have been expected to live with might have been more tricky – I haven't come across any similar case.

My

layman’s verdict (for what it’s worth) is that Jane behaved honestly, Tony was just

the sort of husband she deserved, and Bruce was a cad of the highest order.

More civil registration errors

I’m

very relaxed about errors – people are only human, and mistakes will be made

from time to time. The reason that I’ve been highlighting errors in the

newsletter is to remind you that, whilst errors in birth and death registrations

are mercifully rare, they did happen from time to time. Indeed, I’m sure they

still happen very occasionally.

But

before giving some more examples I need to remind you that under the system of civil

registration instituted in England & Wales in 1837 each birth or death

entry normally appears in two registers, the register retained by the local registration

district, and the register created by the staff at General Register Office (GRO).

When a birth or death was registered it was first recorded in the local

register, then at the end of the quarter the local registrar would copy every

entry onto loose sheets which would be sent by post to the GRO to be bound with

other entries of the same type from the same quarter. The bound volumes were

numbered – generally the same registration districts would be bound together

each quarter, so the volume number would be the same – and then the pages

within the volumes were numbered sequentially. Only then could the entries be

indexed – a process that involved copying some of the information again – and

again, so that by the time an entry appeared in the index it had been copied at

least three times!

Note:

in the last

issue I linked to a talk about the early years of civil registration by

Audrey Collins, who worked for many years at the National Archives, and before

that she was at the Family Records Centre in Islington, where the GRO indexes

could be accessed by members of the public free of charge until 2007.

The

existence of two register entries, one in the local registration district, one

at the GRO is important, because it means that errors can be introduced at the

time of registration, in the process of copying the local register entries for

transmission to the GRO, or – in either case – when a copy certificate is

produced to fulfil an order from a customer.

I

specifically mentioned birth and death certificates above because we all know

that information in marriage registers can be incorrect, for a whole range of

reasons. And, in the case of marriages, each entry can appear in as many as

three registers – the church register, the local register, and the GRO register

– so there’s even more scope for error.

And

because of human error (and/or bad handwriting), two copy certificates can

contain different information even when they come from the same source. For

example, in 2003 Carol and her cousin independently ordered a marriage certificate

for Carol’s great-grandmother – and they showed different occupations for the

bride’s father. According to one he was farmer, according to the other he was a

tanner – yet each was certified as a true copy of the same entry.

When

something looks wrong it can be quite difficult to figure what actually happened, and this example sent in by Pamela had me

stumped until I remembered I’d seen something similar before:

I

expect you’ve noticed something different about this birth certificate – the time

of the child’s birth has been recorded under the date. In Scotland the time of

birth is always recorded, but in England & Wales the time of birth is only

recorded in the case of multiple births, in order to establish

the order of priority for inheritance purposes. Pamela wondered if James was

one of twins, but if so – where was the other child? There was neither a birth

entry nor a death entry.

And

that’s when I remembered that I’d previously come across a registration

district where in the early years of civil registration the registrar would

routinely record the time of birth. Thanks to the GRO’s new Online View service

riddles like this can be solved quickly and easily – I simply ordered another

birth from the same page in the same quarter:

As

you can see, I was unlucky with my first choice – it appeared to show the word ‘none’

beneath the date, which strongly hinted that my theory was correct, but wasn’t

conclusive. Time to spend another £2.50 to satisfy my curiosity:

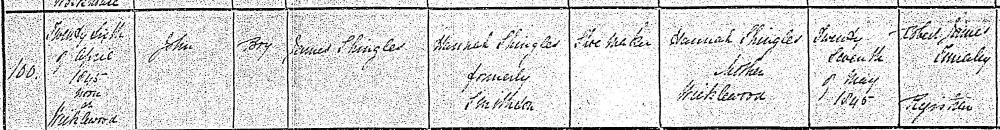

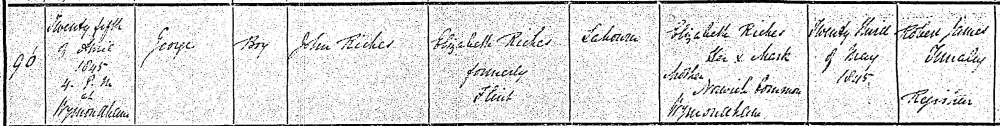

This

time I hit the jackpot – George Riches was shown as having been born at 4pm

(and he wasn’t a twin, either). So that’s one mystery solved – the other

question is how James Minns came to be baptised 2 days before he was born?

© Norfolk Record Office – All Rights Reserved. Used by kind

permission of Findmypast

Clearly

the young orphan can’t have been born on 2nd May, as the GRO birth

register entry states, but why would the wrong date be shown? After all, if we

assume that 25th April (the birthdate given in the baptism register)

is the correct date, the birth would still have been registered within the 42 days

prescribed in the Act. Perhaps before reading on you’d

like to consider how things might have gone wrong?

Here’s

my theory: we know that Susan Minns, James’s mother, couldn’t sign her own name

- so she may not have been very good with dates. Let’s suppose that when she

took the baby to be baptised she was asked when he was

born, and answered “Friday”. There wouldn’t have been much scope for confusion –

James Minns was baptised on Wednesday 30th April, so the vicar could

easily calculate that he had been born on Friday 25th April.

But

suppose that when she went to register her son’s birth

she was asked the same question, and answered “It was a Friday…. let me see, it

must have been 5 weeks ago.” There are two ways that the registrar could have

interpreted this – one would be to count back 5 weeks from the previous Friday,

the other would be to count back 5 weeks, and assume that the child was born on

the Friday of that week. The first approach would lead to a birth date of Friday

25th April, matching the baptism register – the second would imply

that James Minns was born on Friday 2nd May, the date shown in the

birth register.

Of

course, you might have a better theory. If so, don’t write to me, post it in

the Comments on the latest newsletter discussion area at the LostCousins

Forum – you’ll find it here.

Tip:

almost anyone can join the LostCousins Forum, and it won’t cost a penny, just an

hour (or less) of your time. Simply log into your LostCousins account and add

relatives to your My Ancestors page until the Match Potential shown on your My

Summary page equals or exceeds 1. Why is entry to the forum restricted? Because

it’s a reward for the members who do the most to help their own cousins! The

quickest way to increase your Match Potential is to add relatives from the 1881

censuses.

Finally,

an example from my own tree of an error in a marriage certificate. When I began

my research there were no parish registers online, so it was a matter of going

to the relevant record office or ordering a copy of the marriage certificate.

In those days you could obtain certificates from local register offices quite easily:

if you visited in person and they weren’t too busy they would produce the copy

while you waited. Most were able to photocopy a marriage register entry onto a

blank certificate so that the handwriting of the participants was shown,

something that was always nice to have, but could be crucial. This is the local

certificate I obtained in 2002 for the marriage of my great-great grandparents

in 1859:

This

really threw a cat amongst the pigeons – as it was I

couldn’t find the birth of Mary Ann Burns, and here was an official document

telling me that her father’s surname wasn’t Burns, but Brown. It was only some

years later that I checked the entry in the church copy of the marriage register,

which had been deposited at the London Metropolitan Archives:

©

London Metropolitan Archives. All Rights Reserved. Images used by kind

permission of Ancestry

It’s

not just the name of the bride’s father that is shown differently in the church

register – the forenames of the bride and groom are shown in full (other than

the abbreviation for William). The one thing I haven’t done is purchase a

certificate from the General Register Office, though I’m sorely tempted. Will

that register entry match either of the other two, or will it be different

again?

Considering

that DNA tests are quite expensive, you’d be surprised how many family

historians – even LostCousins members – don’t make very good use of the results

they get. Some focus on the ethnicity estimates (almost certainly a waste of

time), and most spend their time figuring out how they are connected to their

closest matches (whilst there is some merit in this it shouldn’t be your priority).

As I explained to the audience at the Suffolk Family History Society Fair last

month, the biggest mistake is to forget why you tested – surely it was to fill

in some of the gaps in your tree by knocking down ‘brick walls’?

Fortunately

there’s a way to keep your focus – follow the advice in my DNA

Masterclass. It tells you everything you really need to know, and sets out

simple, straightforward steps that anyone can follow. I’ve been working with

DNA for well over 10 years, and have taken every DNA

test from every major provider – I know what works and, more importantly, I

know what doesn’t work.

A

couple of miles north of the ancient Essex village of Great Chesterford you’ll find the Cam Valley Crematorium. A

recent innovation on the site is a memorial post box, a place where relatives

can deposit letters or cards addressed to loved ones who have passed away – you

can see a picture in this newspaper article.

I hope it brings comfort to those who use it.

Those

letters won’t be opened or read – and that was almost the fate of a cache of

letters written in 1757-58 to the crew of a French warship that was captured by

the Royal Navy during the Seven Years War. It is only now that they have been

read, by a Cambridge professor who unearthed them in the National Archives at

Kew – you can read about the discovery here.

It

probably won’t have escaped your notice that Black Friday is fast approaching.

In the next issue I’ll be unveiling the best offers from the world of genealogy

and giving my unbiased recommendations – so don’t fork out until you’ve read the

newsletter!

There’s

one thing that certainly isn’t a bargain these days – First Class post! To

charge £1.25 (twenty-five shillings in old money) to send a letter seems

extortionate, particularly since the latest statistics show that only 73.7%

were delivered next day, compared to the 93% target set by the regulator Ofcom.

Thankfully I have all the 1st Class stamps I’m ever likely to need, purchased

at half the current price.

Whilst

on the subject of things going up, today’s

announcement that inflation in the UK has fallen to 4.6% won’t affect next year’s

pension increase – State Pensions will be going up by 8.5% in April 2024, based

on the increase in average earnings. Some good news at last!

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Remember that this year’s seasonal competition has already started,

so entries you add to your My Ancestors page not only increase your

chances of connecting with living cousins, they

increase your chances of winning multiple prizes in the competition! (See this article

for more information.)

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2023 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!