Newsletter – 25th

May 2023

My ancestor was in the militia

Are you researching with one hand tied behind

your back?

It helps if you know what you’re looking at

More details on the forthcoming bigamy symposium

Could this be the last chance to save on WDYTYA

subscriptions? EXCLUSIVE OFFER

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 10th May) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009,

so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

My ancestor was in the militia

If

you were male, born before World War 2, and lived in the UK, the chances are

that you were required to do National Service, serving in the military for 2

years (or 18 months for those called up between January 1949 and September

1950), and remaining on the reserve list for a number of

years afterwards. There were some exemptions – primarily for those working in coal

mining, farming, or the merchant navy – but most did their stint.

Similarly many of our male ancestors would have served

in the militia in the second half of the 18th century, or the first

half of the 19th century: English and Welsh regiments were established

by the Militia Act 1757, Scottish and Irish regiments were formed later.

Organised by county and chosen by ballot, service was compulsory – though from

the 1790s you could get off the hook by persuading another man to take your

place, perhaps by offering them some financial inducement.

Members

of the militia were chosen from able-bodied men between 18 and 45 (18 and 50 between

1757-62), and rather like the modern Territorial Army (now the Army Reserve)

they would train for a number of days annually, but would

usually only be called up in time of war. During the Napoleonic Wars the period

of service was increased from 3 years to 5 years.

Note:

men with children might be exempt – before 1802 this typically only applied to

men with 3 or 4 children under 10, but from 1802 men with any children under 14

were exempt. Many officials were exempt, as were clergymen, teachers, doctors, apprentices,

and those who had previously served in the militia. There was also a minimum

height requirement, usually 5ft 4in – this might seem like a low bar, but the

average height of adult males in those days was about 5ft 7in so there could

have been around 10% or more who were too short.

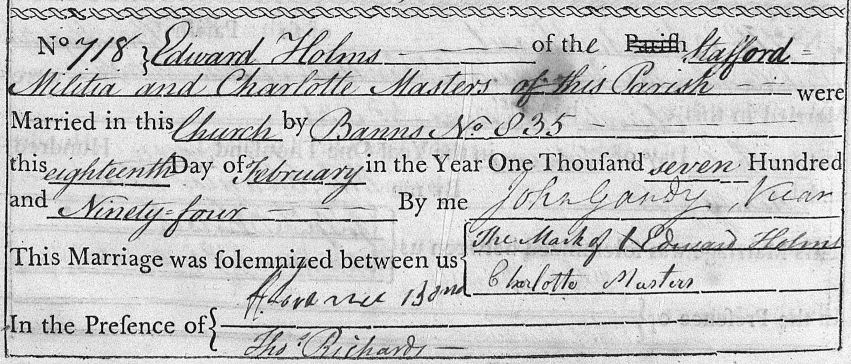

Usually militia regiments served on the Home Front, though

not in the same county from which the men were drawn. For example, when my

ancestor Edward Holmes married a local girl in Plymouth, Devon in 1794 he was (according

to the marriage register entry) serving with the Staffordshire militia, so

would have been over 200 miles, or two weeks’ march, from home.

Tip:

it’s worth considering whether some of your male ancestors might have relocated

as a consequence of serving in the militia.

Most

records of the militia are held at the National Archives in Kew, but there are

some at local records offices. Of particular interest are the annual militia

ballot lists, which are akin to local censuses. According to Militia Lists and Musters 1757-1876 (sadly

out of print) particularly good collections survive for Cumberland, Dorset, Hertfordshire,

Kent, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire and Bristol.

Are you researching with one hand tied behind your back?

I

mentioned in the previous article that my great-great-great-great grandfather

Edward Holmes married in Stoke Damerel, Plymouth,

Devon in 1794 and is recorded in the marriage register as being in the Staffordshire

Militia.

Naturally

the first place I looked for his baptism was Staffordshire – Findmypast have exclusive rights to the

parish registers at Staffordshire Archives. He died a few months before the

1841 Census, but if the age of 78 given in the burial register and on his death certificate are correct he must have been born around

1762-63. However that would make him 31 when he

married in 1794, which is on the high side for a first marriage, so I wasn’t

surprised that the only baptisms I could find were in the early 1770s. Perhaps

he was 68, not 78? Even today people struggle with subtraction.

When

there is a choice of baptisms and little to choose between them

I generally take a look to see what others have done, just in case they’ve spotted

some clues that I’ve missed. But in this case the only distant cousins who had attached

a baptism to Edward had

chosen a 1771 baptism in Halifax, Yorkshire – and I wondered why those 18

researchers had plumped for this baptism ahead of the Staffordshire entries. Did

they know something that I didn’t?

I

didn’t look at every tree, but what I did notice was that although they all

recorded Edward’s marriage in 1794, none of them provided any supporting sources.

I soon realised why – although Ancestry have a large collection

of Devon parish records, they don’t have images of the parish registers, and

the collection doesn’t include every parish. In particular,

marriages from St Andrew, Plymouth seem to be missing altogether, at

least for the relevant period.

Note:

during my investigations I stumbled across an index entry for Edward Stanley

Gibbons – a name that might not mean much to you, but as a young stamp collector

the name ‘Stanley Gibbons’ (he dropped the ‘Edward’) was one to conjure with. Gibbons

was baptised at St Andrew, Plymouth in 1841, but the transcript

gives only the year, not the date.

I

suspect that my cousins found the marriage record at the free FamilySearch site,

where there is not only a transcript but an image:

© Image copyright Plymouth Archives; used by kind permission of

Findmypast

However,

whilst the image does record the marriage of Edwd Holms

to Charlotte Masters it’s not a page from the marriage

register – remember that in 1754 new marriage registers were brought

into use, and whilst they didn't have to be printed most were, and even if they

weren't the entries needed to be separated by ruled lines.

© Image copyright Plymouth

Archives; used by kind permission of Findmypast

© Image copyright Plymouth

Archives; used by kind permission of Findmypast

The

actual marriage register entry provides the key information that Edward Holms was

serving in the Stafford Militia – in fact, if you look through the register you’ll see that many of the grooms who married at St

Andrew, Plymouth were soldiers or sailors.

As

it happens, the Edward Holmes who was born in Halifax, Yorkshire was also in

the army, and there are records relating to his discharge and pension on Findmypast

and Ancestry which make it clear that he was a weaver by trade, who was discharged

from the 2nd Regiment of Dragoon Guards in 1808 after 18 years service on the grounds of ill-health (a rupture), and

awarded a pension of 1s a day. Is it credible that the same man would be described

in baptism register entries in 1804, 1808, and 1810 as a bricklayer?

To

me this is a clear case of researching “with one hand tied behind one’s back” –

if you only have access to records at one of the major subscription

sites you’re bound to make mistakes from time to time.

Tip:

if you can’t afford two annual subscriptions check what’s available at your

local library. You might also be able to get free access at a nearby record

office, LDS Family History Centre, or through your local family history

society. If none of those options work for you, consider buying shorter

subscriptions, or alternating your annual subscriptions.

It helps if you know what you’re looking at

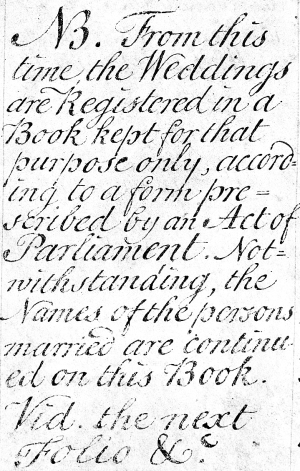

In the previous

article I showed extracts from two parish registers, both from the same parish

and both recording the same event – though with different levels of detail. It’s

not unusual to find alphabetical indexes to marriages, baptisms, or burials at

the front or back of a parish register but in this case the entries are in the

same chronological order as in the register.

In the previous

article I showed extracts from two parish registers, both from the same parish

and both recording the same event – though with different levels of detail. It’s

not unusual to find alphabetical indexes to marriages, baptisms, or burials at

the front or back of a parish register but in this case the entries are in the

same chronological order as in the register.

The

low detail entries are recorded in the composite register that was already in

use when Lord Hardwicke’s marriage law came into force in 1754. At the front of

the register I found a note, probably dating from the

18th century, which mentioned the duplicate entries, and referred to

a more detailed note in the pages relating to 1754.

©

Image copyright Plymouth Archives; used by kind permission of Findmypast

On

the left you can see that note – clearly the vicar at the time decided that it

was worthwhile continuing to keep a record of marriages in the same register as

baptisms and burials, though precisely what his reasoning was is difficult to

guess 269 years later!

The

new Act made a big change to the way that entries were recorded that might not

be immediately obvious, even to experienced researchers (as almost all readers

of this newsletter are). Because the

participants in the marriage ceremony – the bride, the groom, the witnesses,

and the clergyman – all had to sign the register, it meant that it couldn’t be locked

away in the parish chest and only brought out when the incumbent decided to

write up all the baptisms, burials, and marriages that had taken place since

the previous occasion (which could have been weeks or months earlier). Vicars would

have relied on the sexton’s notebook, on notes they had taken themselves, or

sometimes on their memories (which given the number of gaps and errors may not

have been as reliable as they would have wished).

Parish

chests were required to have three locks, with one key held by the clergymen

and the other two by a church warden and another member of the community. You

can see examples of parish chests here

and here – the chest

in the first photo dates from the 1400s, and had to be modified in the 16th

century when the requirement for three locks was introduced.

It

may be that the vicar of St Andrew, Plymouth was concerned that the new

marriage register might be lost or damaged whilst in use, or perhaps he just liked

the idea of having all the entries in a single register. Whatever his

reasoning, the practice wasn’t a common one.

It’s

understandable that family historians who are less experienced (or, at least,

less experienced in researching English parish records) might not have realised

that there was another more detailed entry in a separate register. However the key lesson for all of us is the importance of

knowing what we are looking at!

Guest article: An introduction to Geneanet

It’s impossible for me to research every

genealogy site in the depth that LostCousins members deserve, so I’m delighted

that Derek has offered to tell you about Geneanet….

Peter

has asked that I share my experiences of Geneanet, an

alternative to Ancestry, but in fact Geneanet and

Ancestry are now in collaboration with each other and share both information

and family trees (however, Geneanet has assured its

members that it will exist as a separate site within the Ancestry family). It

is available in English, has 5 million members, and has 8 billion individuals

in family trees. The free version is simple to use but the paid version (Premium),

gives you more in-depth searches and feedback, and at a cost of £11 for 3 months

will not break the bank!

The

basic premise of Geneanet is collaboration; you

upload your tree with pictures, archive records, and other information you

think relevant; this data is then freely available for others to access. In

addition to the members’ interests there are the usual government census

returns and marriage certificates, plus, the standard records one would expect

from a genealogical site. Members not only submit records but can be involved

in other projects such as photographs of cemeteries (currently 100 countries)

and war memorials, both European, and worldwide. In addition

Geneanet has a DNA database that is free to upload

and free to access and link to; within the DNA you can search on the usual such

as segments, accuracy degree of relationship, etc.

My

experience was of an American service man who married a French lady with Jewish

ancestry. She thought her father was linked to Romania and Hungary and with that;

the WW2 associated problems of her ancestry; whilst her mother’s side was

linked to different villages within France. I had tracked down the UK side of

her husband’s tree but all I had for her was a name of her mother and place of

birth, (but no date of birth), and a possible father with roots in Romania.

The

search on Geneanet showed her grandparents on both

sides with those of her father originating in Ploesi,

Romania and the mother’s in villages within France. I

then used this information to search further on Geneanet

and Ancestry. I am not a Premium member but initially working with Geneanet and then Ancestry I have downloaded a number of certificates and further ancestors. She now

remembers the names of the family members found in France are part of her

family tree, and with that it demonstrates we are on the correct lines. So far we are back to the late 1700’s and have found further

family in Romania, and also in the USA and Sweden.

With

regards to the DNA upload the most I have is up to a 20cm link to most of the

DNA uploads as they are all remote and in Europe. However

I have found a strong link to a family in NZ who are on no genealogical site

other than Geneanet and I look forward to researching

it more closely.

Without

Geneanet I don’t think I would have achieved the

level of detail found, so I would recommend it for those with European links. However its main attraction is that a good proportion of the

site is free and if needed £4 per month or so is not bad.

More details on the forthcoming bigamy symposium

In

the last issue I mentioned

the event taking place at Macquarie University in Australia, in July. I’ve now

received some more information on the individual sessions, and you can view it here.

For

those of us in the UK most of the sessions are in the middle of the night. However if the subject matter is of interest I recommend

registering anyway, as the talks are likely to be recorded and made available afterwards

(but, as with so many other online events, access might well be restricted to attendees).

You only die twice

A

letter in the latest issue of Who Do You Think You Are? magazine really

struck home – and not just because it was written by a LostCousins member.

I

hadn’t previously come across the saying that we all die twice, once when we

stop living, and again the last time that someone remembers us – but it certainly

makes me feel proud of the way that we family historians bring our ancestors

back to life by researching them.

It

makes it even more important that our research lives on, whether because we

hand it over to a member of the younger generation who is keen to continue it, or

– more likely – because we share our discoveries with our many ‘lost cousins’.

Could this be the last chance to save on WDYTYA

subscriptions? EXCLUSIVE OFFER

The

exclusive offer I’ve arranged for LostCousins members is still running but it

can’t last for ever.

I've

been a reader of Who Do You Think You Are? magazine ever since issue 1,

and I can tell you from personal experience that every issue is packed with advice

on how to research your family tree, including how to track down online records,

how to get more from DNA tests, and the ever-popular readers' stories. Naturally

you also get to look behind-the-scenes of the popular Who Do You Think You

Are? TV series.

There's

an extra special introductory offer for members in the UK, but there are also offers

for overseas readers, each of which offers a substantial saving on the cover

price:

UK - try 6 issues for just

£9.99 - saving 68%

Europe - 13 issues (1 year)

for €65 - saving 33%

Australia

& New Zealand

- 13 issues (1 year) for AU $99 - saving 38%

US

& Canada

– 13 issues for US $69.99 – saving 59%

Rest

of the world

- 13 issues (1 year) for US $69.99 – saving 41%

To

take advantage of any of these deals (and to support LostCousins) please follow

this link.

I’ve

been ordering goods from Amazon for the past 20 years and for the most part the

service has been amazing. But last week they couldn’t deliver the screwdriver

set I ordered because they couldn’t find my house – that’s right, the one they’ve

been delivering to for two decades. Ironically this happened on the same day

the NASA awarded a $3.4 billion contract to Blue Origin, the space company owned

by Jeff Bezos, the founder and executive chairman of Amazon. Let’s hope that

the navigation software that takes astronauts to the moon is more reliable than

the software that Amazon delivery drivers use!

Note:

the same thing happened the next day – another parcel failed to turn up. Fortunately both eventually arrived, 2 or 3 days late, and just before my patience ran out!

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2023 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!