Newsletter - 21st June 2019

Latest Ancestry updates BREAKING

NEWS

An image from the past: how an author found his grandfather EXCLUSIVE

The historic links between clothes manufacturing and slavery

Coins that you won't find in your change

The difference between documented cousins and genetic cousins

Latest DNA offers ENDING SOON

Review: Last Train to Hilversum

Review: Tracing Your Female Ancestors

Review: Tracing Your Potteries Ancestors

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published 2

or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue (dated 8th June) click here; to find

earlier articles use the customised Google search between this paragraph and

the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009, so you don't

need to keep copies):

To go to the main LostCousins website click the

logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join -

it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition

of this newsletter available!

Latest Ancestry

updates BREAKING NEWS

Just as I was finalising this

newsletter Ancestry added dozens of new genetic communities, bringing the total

number of UK communities to 73, and providing a more detailed analysis of

ethnicity than ever before. Some of the areas are overlapping, so be careful how

you interpret the data, but at first sight this is definitely

a step in the right direction.

I'm only included in two

communities, though to be fair they cover the area where most of my ancestors

originated - but my mother-in-law's results are really impressive, showing her to

have ancestors from three parts of Wales, as well as Gloucestershire - which ties

in very well with what we know about her tree. My wife's results are equally

impressive, adding an extra region of Wales which we know appears in her

father's tree.

To mark the launch Ancestry

are offering discounted DNA tests in the UK, though only until Tuesday 25th

June - follow this link

to take advantage of this offer (and support LostCousins at the same time - it won't

cost you a penny more). You may need to log-out before clicking the link.

All of Ancestry's recent enhancements

are related to DNA, which emphasises how important DNA is nowadays - not just

to Ancestry as the world's leading provider of DNA tests to the genealogy

community, but also to us, the family historians with previously indestructible

'brick walls' in our trees.

As from 1st July DNA Circles

will be permanently replaced by ThruLines, which has

been in beta test since March, and has been continually improved in response to

user feedback (see the LostCousins Forum for an extensive discussion of the

features). I've never been in a DNA Circle, but if any of you have found them

useful you might want to keep a record before they disappear.

The good news is that although

ThruLines is being rolled out across the entire user

base, it will continue to be available to non-subscribers, at least for the

time being. Please bear in mind that ThruLines should

be treated like any other hints - as somebody said to me today, the feature is

called ThruLines, not TruLines!

Also coming in next month will

be the facility to search your matches by name - this is something I'll

personally find very useful because of the number of tests that I manage. The new

DNA matching system will also be brought in for all users - if youíre not

currently an Ancestry subscriber it's worth knowing that all users can see 5

generations of their match's public tree (previously only subscribers could see

any part of their cousin's tree).

The MyTreeTags

system, which has been in beta, will also roll out across the entire user base

from July. There's currently a minor problem which I noticed and might affect some of you -

when MyTreeTags is enabled it's currently not possible to post or view comments against

relatives on someone else's tree,

a feature I've found very useful in the past

Update: since this article was published

Ancestry have confirmed that it wasn't intended to disable comments, and that their developers are

currently working to resolve the issue.

An image

from the past: how an author found his grandfather EXCLUSIVE

The Jayne Sinclair series of

genealogical mysteries is based around historical events, which are always meticulously-researched

by author MJ Lee. Will this account of how he managed to find a photograph of the

grandfather he never knew inspire you to make similar discoveries?

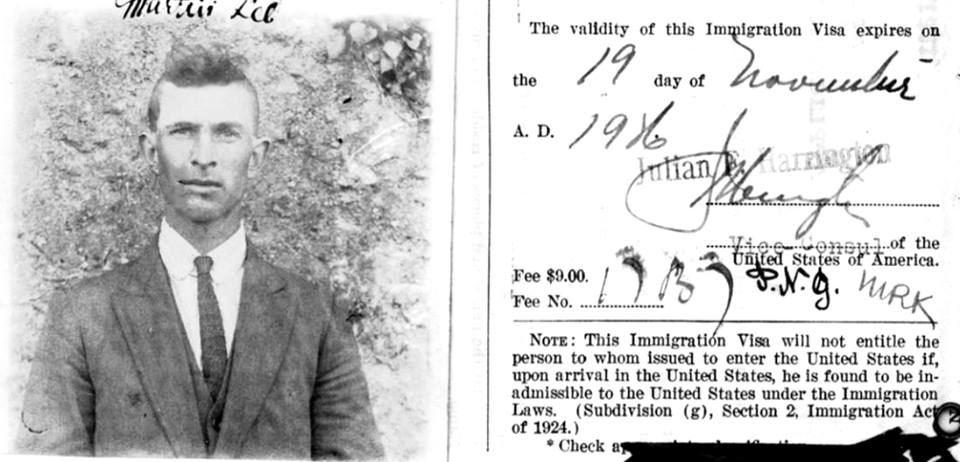

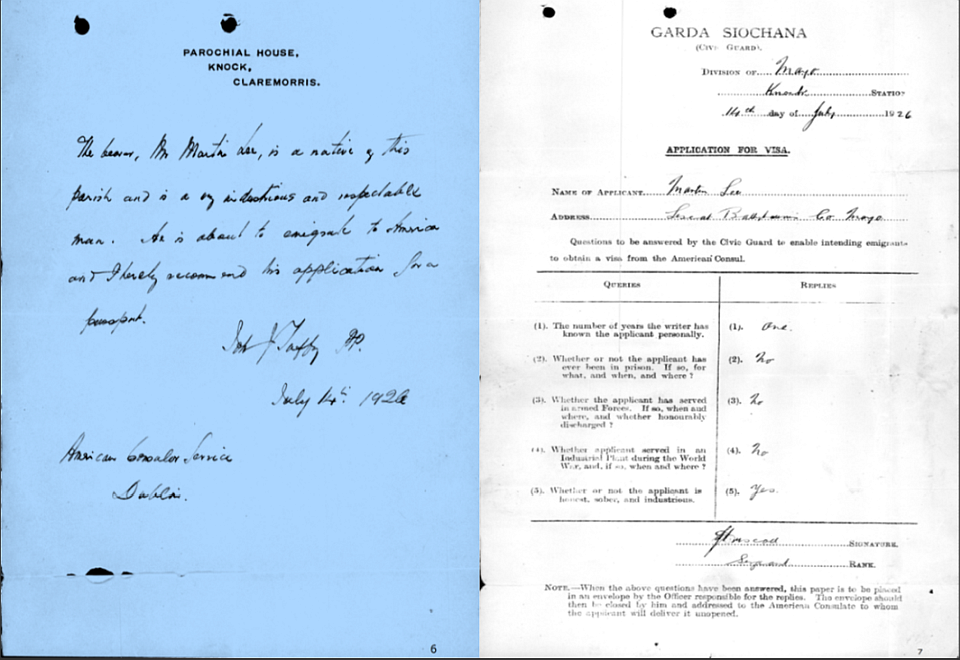

I grew up never knowing what my grandfather looked like. We never had any photographs in family albums nor did we have any letters. Yet, just three months ago, I discovered a photograph of him, hidden in the most unlikely of places; a visa application for the United States of America.

It may be an unlikely place to look, but a branch of the US Department of Homeland Security, US Citizenship and Immigration Services, hold visas from applicants all over the world who went to America from 1924 onwards. Plus a variety of forms, applications for citizenship, supporting letters, and other materials from 1906 to 1956.

Before 1924, visas werenít necessary for people wanting to visit, or emigrate permanently, to the USA. After 1924, new immigration laws meant that all travellers had to have a valid visa. In 1926, my grandfather applied and was granted a visa in Dublin.

You can imagine my shock when I received the disc with this image, the first time I had ever seen his face.

In addition, there were other attachments I received from the USCIS, documents he included to support his application. His original form, his birth certificate and two letters from the parish priest and the local police sergeant regarding his character.

Other information that may be included (but wasnít in my grandfatherís package) could be medical certificates, family history and relatives, details of relations in America, sponsor details and employment information.

The information from the USCIS comes on a disc and the service is quick and efficient. Remarkably, they also respond almost immediately to emails. "Whereís the catch", I hear you say? The cost.

Itís a two-step process. First you have to apply for a visa number (itís not the same as the one on the Shipping Manifest). With this number you can then apply for copies of all the information they hold - they will send you everything they have on an individual.

Unfortunately, each step costs US$65.

But for me, seeing my grandfatherís face for the first time was priceless.

You may also be asking why I had never seen his photograph before. Three years after this photograph was taken, he died of bronchitis and a heart attack in a Brooklyn hospital, aged 32. His intent had been to bring across his wife and family (including my father) to America once he had settled down. A goal he was never able to deliver. Instead, my father later travelled to the UK to work and I was born there.

As ever in family history, there are hidden secrets as well. What the generous testimonial from the priest and the policeman donít reveal is that he was a company commander for the IRA in the district during the Irish War of Independence 1918-1921. And was probably interned (but not imprisoned) during the Irish Civil War of 1922-24.

All family history documents only deliver the bare bones. It is the stories behind the papers that bring them to life. Or in my case, a single picture that brought my Grandfather back into my life.

Note: information on the holdings of the USCIS can be found here.

If you missed my review of

the latest Jayne Sinclair mystery (The Sinclair Betrayal) you'll find it

here.

And there's good news for those who prefer traditional books - the paperback

version has now been released (the links in the review will work for either

version). ††

An article

on the BCC website led me to this YouTube video

of moving images from the final years of Queen Victoria's reign, including some

of the only surviving footage shot on 68mm film. Can you spot Queen Victoria in

sunglasses? You might even see her smiling if you look closely....

The historic links

between clothes manufacturing and slavery

In the 21st century clothes

retailers are being pressured to ensure that the clothing they sell isn't

produced by workers who are the victims of modern slavery (see, for example,

this Guardian report).

But two centuries ago clothes

were moving in the opposite direction - Welsh weavers were making woollen clothing

for slaves in the Caribbean to wear, as this BBC article explains.

Coins that you

won't find in your change

In the last issue I wrote

about farthings, which weren't minted after 1956, and seemed to disappear very

quickly after that (although they remained legal tender until 1960). This

prompted Miranda to write about guineas, coins which weren't minted after 1813,

but the unit was still being used for pricing purposes when I was young.

Indeed, even today, racehorses sold at Tattersalls are priced in guineas.

Guineas weren't always worth

21 shillings - at one time their value fluctuated as the relative prices of

silver and gold changed. Eventually sovereigns took

over from guineas, and had a fixed value of 20

shillings (or 1 pound), but even though they're still minted for collectors,

you won't find one in your change. Nevertheless, sovereigns are still legal

tender, though since the gold content is worth far more than £1

you'd be foolish to use them to pay your grocery bill.

The highest value English

coin in mediaeval times was the noble, worth 6s 8d, or one-third of a pound - you

can see an example from c.1425 here.

A few years after that coin was minted the price of gold rose, so that the intrinsic

value of the coin exceeded its face value, resulting in most of the coins in

circulation finding their way to Europe. In 1464 the value of the noble was increased

from 6s 8d (80 pence) to 8s 4d (100 pence) in a belated effort to stem the flow.

However, whilst the noble was

the most valuable coin, you'll sometimes see marks mentioned in records. A mark

was worth 13s 4d, ie twice as much as a noble - but it

didnít exist as a coin, it is said to have been introduced by the Danes as a unit

of account. (When Richard the Lionheart was captured in 1193 his ransom was set

at 150,000 marks by the Holy Roman Emperor.)

When I was young, adults

talked about silver threepenny (pronounced 'thrupenny') bits, but the last

sterling silver coins were minted in 1919 - after that the silver content was

reduced to 50%. Children of middle-class families were delighted to discover silver

threepences (or even sixpences) in their Christmas pudding - or so I was told

when I was a boy. †

Another silver coin that

always fascinated me was the groat, worth 4d and last

minted in England in 1855, and I eventually managed to buy a battered example

for a few pounds, just to satisfy my curiosity. I'd show you a picture, but

it's so small that it would be a struggle to photograph (however, there are

some excellent images on this Wikipedia page).

The

difference between documented cousins and genetic cousins

A cousin is a cousin - right?

Well, not really - there is a big different between a documented cousin,

one whose precise relationship to us can be demonstrated by reference to

historical records, and a genetic cousin, someone who shares our DNA,

but whose connection is unknown.

The deceased cousins you

enter on your My Ancestors page, the living cousins you find as a result,

and the rest of the blood relatives on your family tree are documented cousins

- because you can prove how you're connected using records (usually paper records,

but you might access them as microfilm or digital images). By contrast the

cousins you find when you test your DNA are genetic cousins - people who share

a common ancestor with you that is evidenced by shared segments of DNA.

But simply knowing that someone

shares your DNA is pretty meaningless - other than a very small number of close

matches the relationship could be 10th cousin or more distant, and since we all

have around 100 million living relatives who are 10th cousin (or closer), it's

not telling us anything we didn't already know. Indeed, it would be more interesting

to discover that another person with a similar ethnic background isn't

related to us!

When I was studying for my

MBA 20 years ago I learned the difference between data,

information, and knowledge - and it's a useful way to think about

DNA results. When we take a DNA test the results provided by the chip are mere data

(the 'raw data' that you can download and transfer to other sites); the

challenge for the company that sold us the test to turn that data into meaningful

information, which in most cases they do by providing us with lists of people

who share the same segments of DNA, and producing ethnicity estimates, statistical

analyses that look for similarities between our DNA and that of representative

samples of populations around the world. ††

But turning data into information

is only the first step - it's up to us to take the next step, turning that

information into knowledge. One of the ways we can do this is by finding people

who have the same ancestors in their online tree, and if you test with Ancestry they'll tell you when this is the case. However,

it's likely that fewer than 1 in 1000 of your matches will be resolved in this

way - partly because some people haven't linked a tree to their DNA results,

but mostly because the common ancestors are on the other side of a 'brick wall'.

This could be a 'brick wall' in your tree, a 'brick wall' in your cousin's

tree, or 'brick walls' in both trees.

Sounds daunting doesn't it?

But remember, the primary aim of testing our DNA is to knock down our 'brick

walls' by overcoming deficiencies in historical records. Whether the records

have been lost, destroyed, falsified, or simply didn't exist in the first place

we can use DNA to bridge the gap - provided it's within the reach of autosomal

DNA, in practice usually means the last 250-300 years.

Sometimes we have a theory as

to who the parents of an ancestor might have been - but without any record of a

baptism, or other supporting documentation (such as a will or family Bible), they're

going to remain just theories. But if we share DNA with someone who is

descended from the same family, or even from an earlier generation of the same

family, we're well on the way to proving our theory.

Take an example from my own tree:

I knew from the censuses that my 3G grandmother Elisabeth Goode was born around

1787 in Great Barton, Suffolk - and there was a Goode couple baptising children

in Great Barton around that time. However, there is absolutely no record of my

ancestor's baptism - and whilst this could have been a clerical error, I was also

aware that the Stamp Duties Act of 1783 (which placed a tax of 3d on baptism,

marriage, and burial register entries) had not only discouraged some parents

from having their children baptised, but also encouraged the clergy to carry

out baptisms which were not recorded in the register.

Note: although a baptism

register entry provided the right to settle in the parish this was less important

for daughters than for sons, as on marriage a woman would acquire settlement

rights in the same parish as husband.

Soon after testing with

Ancestry I had a DNA match with a descendant of Mary Ann Goode, who - if my

theory was correct - was my ancestor's sister. The amount of DNA we shared was

consistent with us being 4th cousins once removed, and as there were no other Goode

families in the village at the relevant time I determined that the evidence was

overwhelming - after nearly 15 years of searching it was time to change the dotted

line in my tree to a solid line.

It wonít always be as easy as

- in that case there was a shared surname in our trees, which meant that the

match was picked up when I followed the strategies in the Masterclass.

More often you'll identify the genetic cousins worth focusing on by looking at shared

matches: when you and a documented cousin both match with the same genetic

cousin, you can be fairly certain that the match with the genetic cousin is in

the part of your tree that you share with your documented cousin.

Note: it doesn't need to

be the same DNA segment.

What this illustrates is the

importance of having documented cousins who have tested their DNA. Now, you

could buy test kits for your cousins and persuade them to test, but it's much cheaper

and easier to find cousins who have already tested - as most active LostCousins

members have. This is why, when you find a 'lost

cousin' you can see instantly whether or not they've tested, and why one of the

first steps in the DNA Masterclass is to complete your My Ancestors page. In fact, this is something you can (and

should) do while youíre waiting for your DNA results - or even before you order

your test.

DNA testing doesn't reduce

the importance of conventional research - instead it provides a new tool that

maximises the value of your records-based research skills. When I started

researching my tree some people were still questioning whether computers were a

useful tool for genealogists - don't make the same mistake when it comes to DNA!

†

Latest DNA

offers ENDING SOON

There always seems to be

somebody offering DNA tests at a discount - which I guess is an indication of

how competitive the market has become. This week MyHeritage announced offers

which run until the end of June:

My

Heritage (UK) - £59 plus shipping (free if you order 2 or more) until

9.59pm on 30th June

My

Heritage (US) - $69 plus shipping (free if you order 2 or more) until

9.59pm on 30th June

My

Heritage (Australia) - details not available at time of publication (please

use the link)

MyHeritage are believed to

have sold more tests in continental Europe than any other provider - if you're

keen to connect with cousins in countries where Ancestry don't sell their test

(such as Germany) either test with MyHeritage, or transfer your results from another

provider (there is a one-off charge if you want all of the

features).

Ancestry.co.uk

- £59 plus shipping until 25th June (you may need to log-out first)

Ancestry have sold many more

tests to family historians around the world than any other provider - and

because they don't accept transfers, the only way to get access to their

enormous database is to test with them. My only regret is not testing with

Ancestry earlier!

Review: Last

Train to Hilversum

Radio was a very important part of my youth, whether

it was Listen With Mother, Music and Movement (which we had to listen to at infants school),

or Uncle Mac (officially known as Children's

Favourites); at home we had an extremely

heavy portable radio which required an expensive battery - it cost the

equivalent of a year's pocket money in those days.

Radio was a very important part of my youth, whether

it was Listen With Mother, Music and Movement (which we had to listen to at infants school),

or Uncle Mac (officially known as Children's

Favourites); at home we had an extremely

heavy portable radio which required an expensive battery - it cost the

equivalent of a year's pocket money in those days.

As

I grew older Pick of the Pops and Radio Luxembourg In the 1960s it was only

listening to pirate stations on a transistor radio that made the journey to

school bearable - my favourite was Radio London (do you remember the 'Wonderful

Radio London' jingle - you can hear it here). I went to school

with Noel Edmonds, who started his career on Radio Luxembourg in 1968, but soon

transferred to the fledgling Radio 1, and at the end of the 70s I found myself

spending hours at the computer shop in North Barnet run by Chris Cary, better

known to Radio Caroline listeners as 'Spangles Muldoon'.

Around

the same time I started taping the omnibus edition of The Archers and continued up to 2011,

when my father died and I was no longer making regular long car journeys. Perhaps

I'll catch up on the years I've missed when I find myself in a care home!

Unlike

me, Charlie Connelly, author of Last Train to Hilversum: a journey in search of the

magic of radio, is clearly as committed to radio as he ever was - the history, the

stories, and the interviews he carries out mean as much to him as researching

our family tree does to us. Long before reading this book I knew that Chelmsford

was a key place in the history of radio - it was the town which Marconi chose

for his factory - but I didn't realise that lowly Writtle, where my great-great-great-great-great

grandmother contracted her first marriage also played a starring role.

During

the journey to Hilversum, we learn a little about the technology and the seat-of-the-pants

approach of the early pioneers, but a lot more about the presenters - the

voices that came into peoples' living rooms (and in some cases still do). It's a

very enjoyable ride, one which takes in the Electrophone, a forerunner to

wireless which came to Britain in 1895, though by 1908 there were only 600

subscribers, and even at the peak in 1923 there were still only 2000

subscribers.

We

meet John (later Lord) Reith, who applied for the job of General Manager at the

newly-formed British Broadcasting Company without knowing the first thing about

broadcasting - yet shaped the way that the BBC developed for years to come - and

we also encounter presenters past and present.

Many

years ago I bought a tape copy of Orson Welles' famous

War

of the Worlds

dramatisation, which supposedly sparked panic when it

was broadcast in 1938 - but Connelly comprehensively demolishes the myth. More shocking

for me, however, was to learn that Marconi ended his life a supporter of

Mussolini - I guess that rich successful businessmen don't always make good

choices when it comes to politics.

As

you can probably tell, I enjoyed reading this book, and I suspect you will too.

I bought the hardback - it was a good-as-new copy at a big discount (the paperback

isnít due out until January 2020); there's also a Kindle version and an

audiobook if youíre that way inclined. †

Amazon.co.uk††††††††††††††††††† Amazon.com†††††††††† ††††††††† Amazon.ca††††††††††††† Wordery

Review:

Tracing Your Female Ancestors

It's almost always more difficult to trace female

ancestors, for the simple reason that they usually take their

†husband's surname when they marry.

When I began my research this generally meant that I had to buy birth certificates

in order to find out the mother's maiden name, which would then enable me to

find the parents' marriage, and ultimately their births and/or baptisms.

It's almost always more difficult to trace female

ancestors, for the simple reason that they usually take their

†husband's surname when they marry.

When I began my research this generally meant that I had to buy birth certificates

in order to find out the mother's maiden name, which would then enable me to

find the parents' marriage, and ultimately their births and/or baptisms.

This process took time and cost

money - more than some could afford, or were prepared

to invest. But in November 2016 everything changed for researchers with English

or Welsh ancestors when the General Register Office made available new online

birth indexes which included the mother's maiden name from the inception of

civil registration in July 1837. Overnight it because quicker and cheaper for us

to research our 19th century ancestors, especially our female ancestors.

You would expect that a book

entitled Tracing Your Female Ancestors would highlight such an important

change, but it doesn't get a mention, even though the first chapter (out of 6)

is entitled 'Birth, Marriage and Death'. Indeed there's

no mention of the GRO, FreeBMD, or even the fact that

there are online indexes of births, marriages and deaths for the period after

the introduction of civil registration.

So this book clearly wasn't written for beginners, even though

the blurb on the back cover informs potential purchasers that it covers the

period 1815-1914, which is not that long ago - my great-great grandfather was

born in 1815 and my father was born in 1916.

Who was it written

for? The author doesnít make this clear, though since she starts Chapter 3 ('Crime

and Punishment') with the words "On the whole, we women are a law-abiding

lot compared to men and the past was no different" I couldnít help feeling

that she was expecting most of her readers to share her gender. But of course, whatever our own gender, we all have an equal number

of male and female ancestors - so male readers ought to be made to feel equally

welcome.

There are a few careless

errors: in Chapter 4 ('Daily Life') the author confidently states on p.117 that

"Foreign travel required a passport", but in reality

passports weren't compulsory until the First World War (which is just beyond the

scope of the book).

Note: the Research

Guide at the National Archives website confirms that previously "Possession

of a passport was confined largely to merchants and diplomats, and the vast

majority of those travelling overseas had no formal documents", so many

researchers who seek their ancestors' passports will be disappointed.

There's a really

strange error in Chapter 5 ('A Hard Day's Work'), where the author writes

on p.178:

"The first public washhouses were opened following the 1844 Washhouses Act and proliferated after the 1850 Public Baths and Wash-houses Act. Predictably, the first was the Frederick Street washhouse in London, 1842, rebuilt 1854."

It's a small thing, but to say

that the first washhouses opened following the 1844 Act, only to mention in the

next sentence that the first one opened in 1842, is rather contradictory. But

what is the word 'Predictably' doing there - is the reader supposed to infer

that change always started in London?

If so, the word is doubly misplaced

because Frederick Street is actually in Liverpool, not London (see the Wikipedia

article

Baths and wash houses in Britain); it wasn't until 1847 that the first London

washhouse opened.

But that's towards the end of

the book - I'd only got as far as p.8 when I first encountered a passage that

was both confusing and potentially misleading. Writing about baptism records

the author states:

"For elusive records prior to 1837 (and for anyone who didnít realise they still had to register their child) online parish clerks, where volunteers transcribe records, may be found for free. Try www.ukbmd.org.uk/online_parish_clerk."

Is the author telling the

readers that all records prior to 1837 are hard to find, or that only some are?

She continues:

"The Church of the Latter Day Saints website, also free, is another resource (www.familysearch.org) but you must register; www.freereg.org.uk is worth checking. Local libraries have parish records on microfilm, books and transcriptions."

There is no mention of the

much larger collection of parish registers that can be viewed at any LDS Family

History Centre, nor any hint that parish registers are generally held in record

offices. Nor that registers for many areas can be found online at sites

including Ancestry, Findmypast, and The Genealogist (even though the same sites

are recommended in other contexts). In addition, some record offices have put

registers online themselves, eg Essex and the Medway

area of Kent.

Record offices are eventually

mentioned on p.10 in a section about Bastardy Books - but using the

abbreviation CROs - one that some people may not be familiar with. Then a few

pages later (p.18) another confusing sentence appears in a discussion about marriage

licences, bonds, and allegations:

"A bond was a formal intention to marry and similar to banns for those marrying by licence."

I think I know what she

means, but itís a rather strange way of saying it - and, in any case, I

wouldn't describe bonds as similar to banns. Fortunately

she provides a link to a page which explains what bonds really were, but itís a

jolly long URL to type in (www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Marriage_Allegations,_Bonds_and_Licences_in_England_and_Wales)

so some people might choose to remain in ignorance.

Note for authors: nobody

likes having to type in long URLs since it's tedious and there's ample

opportunity for error. Magazines often provide shortened URLs, but the best

solution for books is usually a page of links on the author's website, since

this can be easily updated.

Then on p.29 we read that:

"Up to the 1840s, there were about forty divorces a year and a mere 317 in total by 1857."

The two statistics are incompatible,

so I checked to see which was more likely to be correct: according to Divorced,

Bigamist, Bereaved? by Professor Rebecca Probert (reviewed here)

there were 197 divorces granted between 1800-57, so fewer than four per year,

not forty.

There's another unfortunate slip

on p.31 where the author writes that Charles Dickens' estranged wife Catherine "survived

him by more than a decade" - but in fact Charles died in 1870 and Catherine

in 1879, so it was just under a decade. It's not important in the context of

the book, but if youíre going to include extraneous information, get it right!

Towards the end of the first

chapter (p.40) we read in connection with burial records that:

"Holding records mainly from the 1850s, www.deceasedonline.com has a free index but you must pay for detail."

The crucial word 'onwards' has

been omitted, ie it should read "mainly from the

1850s onwards" - but someone not already familiar with the site might not

realise this.

Similarly on p.42 we read that:

"HOSPREC (Hospital Records Database) is not, at the time of writing, included in Discovery. Records, because of confidentiality, are closed for up to 100 years."

All that is true. But readers

might reasonably assume that the reason the Hospital Records Database isn't

included in Discovery* is because the records are too modern. In fact the database

itself doesn't include any records, itís a finding guide - and you can search

it here.

*Discovery holds more than

32 million descriptions of records held by The National Archives and more than

2,500 archives across the country.

Chapter 2 focuses on

education, and highlights the ways that girls were discriminated against -

although I'm not nearly as shocked as the author by the revelation that,

whereas 69% of men could sign their name when they married in the mid-19th

century, the figure for women was only 55%.

The source of those

statistics isn't given. When I looked at 50 marriages from March to May 1850 for

St George in the East, an east London parish, the numbers I found were very

different - slightly more brides (80%) than grooms (78%) were able to sign

their name. It was only a very small sample, but it does illustrate the importance

of knowing how statistics have been compiled. (Should you want to look further

the entries I looked at were numbered 127-176 in the register - the starting

point was randomly selected.)

Of course, if you donít believe

that an academic education is inherently more valuable than a practical

education then it's harder to argue that our female ancestors were disadvantaged

by being taught household skills rather than being sent to school. In 21st

century Britain we are gradually realising what our forefathers knew long ago, that

teaching people practical skills is often more important than filling their

heads with meaningless facts. Goodness knows, there have been plenty of times

when I've wished that I'd learned woodwork, metalwork, and technical drawing at

school rather than studying Latin, Greek, and history!

Married women didnít have any

money they could call their own until the passing of the Married Women's

Property Act of 1870, but in practice this would have had little impact on the working

class population. And arguably there was an upside, even for the middle-classes

- the lady of the house could buy on credit from the local shops in the

knowledge that her husband would have to foot the bill!

The final chapter is devoted

to 'Emancipation', and deals briefly with some of the

changes in society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Without a doubt women were treated very differently in earlier times -

the changes during my own lifetime are testament to that.

Although I've given the

author quite a hard time in this review, you mustn't think that it's a bad book

- it isn't, and there are lots of useful tips, some of which were new to me. The

main reason I've highlighted errors that I spotted is to avoid readers of this

newsletter being inadvertently misled, but I've also done it in the hope that the

author will be encouraged to use the services of an editor for her next book.

Finally - and this is,

perhaps, more of a personal preference - I would have found it much easier to

read the book if the many examples, some of which are from the author's own

tree, had been separated from the main text.

I read the paperback, which -

at the time of writing - was available from Wordery

at a saving of nearly 30%, with free worldwide shipping. The Kindle version is

slightly cheaper (but only available from Amazon, of course). Please use the links

below to support LostCousins - we'll benefit even if you end up buying something

completely different!

Amazon.co.uk††††††††††††††††††† Amazon.com†††††††††† ††††††††† Amazon.ca††††††††††††††††††††††† Wordery

Note: the book isnít officially

released in North America until August/September, but you may be able to get it

before then from Wordery.

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Review: Tracing

Your Potteries Ancestors

I don't have ancestors from 'The Potteries', the area of

North Staffordshire which became the centre of pottery †production in England, but I nevertheless

found Michael Sharpe's latest book fascinating. Like his earlier Tracing

Your Birmingham Ancestors (see my review here),

it's not only extremely well-written, but crammed with useful information - and

not just about the pottery manufacturers who dominated the area, but also coal

and iron mining (which began as early as the 13th century), the canals, and the

railways.

I don't have ancestors from 'The Potteries', the area of

North Staffordshire which became the centre of pottery †production in England, but I nevertheless

found Michael Sharpe's latest book fascinating. Like his earlier Tracing

Your Birmingham Ancestors (see my review here),

it's not only extremely well-written, but crammed with useful information - and

not just about the pottery manufacturers who dominated the area, but also coal

and iron mining (which began as early as the 13th century), the canals, and the

railways.

The first potteries used

locally-sourced clays, but eventually clay was imported from further afield so

that Josiah Wedgwood and others could produce fine china. At one time there

were over 4000 bottle kilns (so-called because of their shape, not their

function) in the Stoke-on-Trent area, but now only a handful survive.

You'll find information on

all the topics you'd expect (including schools, churches, workhouses, courts,

regiments and militia), as well as a few you might not have expected (such as a

guide to the local dialect). Throughout there are links and suggestions for

those who want to find out more about a specific topic, and at the back there's

a handy 15-page Appendix listing archives and other key resources.

Note: I was delighted to

see that there was almost a page devoted to Sir Stanley Matthews, the first

footballing knight, and not only the finest sportsman I've ever met, but also

one of the nicest people. Sadly I never got to see him

play - the newsreel footage doesn't do him justice - but I did have the pleasure

of watching his spiritual successor (Sir) Trevor Brooking from the terraces.

It's an excellent book which

I can thoroughly recommend. I read the paperback, but there's also a Kindle

edition - though if you can get the paperback at a good discount, it's worth

paying a bit more. Once again Wordery had the best

deal when I checked (but only if I bought from them through Amazon); finally, please

note that the book won't be officially released in North America for a few

weeks:

Amazon.co.uk††††††††††††††††††† Amazon.com†††††††††† ††††††††† Amazon.ca††††††††††††† Wordery

I had a problem with our

Bosch dishwasher last week - it kept coming up with error E:15 and the advice

in the manual and on the manufacturer's website was to

call in a service technician. Hmmm..... that would

have cost a pretty penny!

Fortunately I've encountered a similar problem in the past (with

a previous dishwasher), and knew that water leaking into the bottom of the

machine from the outside could fool it into thinking there was an internal

fault. On the day before I'd carelessly allowed a kettle to overflow while I

was filling it, and water had spread across the worktop - so it wouldn't have been

surprising if some of that water had found its way into the dishwasher.

But knowing that wasn't

enough - I had to figure out how to get the water out, and that's when I found

a video on YouTube. To cut a long story short, once I'd pulled the machine out

from beneath the worktop (not quite as easy as it sounds when it's built-in)

all I needed to do was tip the machine backwards at an angle of 45 degrees a

couple of times. I should mention that the power was switched off all this time

- having almost electrocuted myself at the age of 6 I've been wary of mains

electricity ever since!

I'm not a great fan of

YouTube, but in this case it proved very useful

indeed!

This is where any

major updates and corrections will be highlighted - if you think you've spotted

an error, first reload the newsletter (press Ctrl-F5), then check again before writing to me, in case someone else has

beaten you to it......

That's all for

now, but I'll be back soon. In the meantime, why not log-in to your LostCousins

account and contribute some more data to my project to connect cousins around

the world? It's not only a great way to leverage the benefits of your DNA

results, it's an excellent opportunity to share information with experienced family

historians who are researching the same ancestral lines.

If you've

forgotten your log-in details that's not a problem - your user name is the

email address in the message you received telling you about this newsletter,

and you can request an instant password reminder by clicking this link. (Note:

if you don't want your password to be sent in an email, just ask me to reset it

on your behalf.)

Peter Calver

Founder,

LostCousins

© Copyright 2019

Peter Calver

†

Please do NOT copy or

republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only

granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However,

you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for

permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins

instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?