Newsletter – 28th

March 2023

Prohibited degrees – the inside story

How the GRO coped with flu and COVID

Why you might not find an entry in the GRO birth

indexes

What do the GRO references mean?

The first time I knocked down a ‘brick wall’ using

DNA

Save 25% on Ancestry DNA tests in the UK ENDS MONDAY

From family history to pioneer history

Wartime ration books discovered in cupboard

Did your ancestor work on the railways?

Interpreting Scottish handwriting for the 16th

and 17th centuries FREE

Why did BBC announcers wear dinner jackets – on the wireless?

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 17th March) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009,

so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

Prohibited degrees – the inside story

Professor

Rebecca Probert’s ground-breaking book Marriage

Law for Genealogists is a must-have for any serious family historian

with ancestors from England & Wales – we all have antecedents who bent the

rules when they married.

But

understanding who could marry who and when isn’t just about people who married

when they oughtn’t to have done – the restrictions can also explain why some people

didn’t marry, or why they married at a different time or a different place.

Only by reading the book can you gain a proper appreciation of the obstacles

that sometimes blocked the path of true love.

When

it comes to 21st century marriage law there is a useful online guide

produced by the General Register Office (GRO). It’s not normally available to

genealogists like you and me, because it’s in an area of the GRO website that’s

intended for registrars: I stumbled across it when carrying out a Google search, and thought that you might be interested. The document

is in PDF format and can be downloaded here

(but you may have to be quick as access could be blocked at any time).

How the GRO coped with flu and COVID

I

also found two PDF documents which set out the procedures to be followed during

a pandemic: one, on the GRO Extranet, is entitled Guidance Note for Flu

Pandemic and dated September 2014. It can be downloaded here.

Note the detailed instructions relating to causes of death that must be

referred to the Coroner, and also the acceptable

causes of death – which varied according to the age of the deceased.

The

other is more recent: Instructions for Implementation of the Coronavirus (Emergency)

Act 2020 is dated March 2020 and whilst produced by the GRO is available from

the Royal College of Pathologists website here.

Although

the documents focus primarily on the procedures for registration of deaths

during the pandemics, reading them will provide insight into the procedures in

more normal times - we don’t often get to see the instructions to registrars.

Incidentally

the March 2020 document has a link to the September 2014 document, as well as

to a circular

issued to Superintendent Registrars, Registrars, and others involved in registration

services in February 2020.

Why you might not find an entry in the GRO birth indexes

When

the GRO released their own index of historic births in November 2016 we were

able, for the first time, to discover the mother’s maiden name for births

registered between 1837 and 1911 without purchasing the relevant certificate.

But

the way in which this new index was compiled sometimes causes problems – indeed,

within days of the new index being released I published a newsletter article

highlighting the key differences.

In

particular I pointed out that the illegitimate birth of my great-grandmother in

1842, which had been indexed in the contemporary quarterly index under both the

surname of her father (Roper) and the surname of her mother (Buxton), appeared

in the new index only under the father’s surname. Fortunately I’d bought the

certificate many years before, when the quarterly indexes were all we had to go

on, but these days it’s natural for someone planning to order a certificate (or

PDF) to start their search at the GRO site.

Another

example cropped up recently on the LostCousins forum:

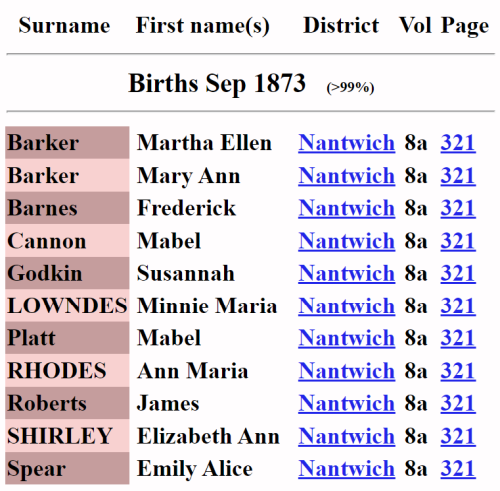

I find a birth index entry for a cousin Mable Cannon on all the usual sites. She was born

Name: Mabel Cannon

Registration Date: 1873

Quarter of the Year: Jul-Aug-Sep

Registration Place: Nantwich, Cheshire, England

Volume: 8a

Page: 321

However, a search of the GRO index returns no

match. I've checked on FreeBMD for other entries on

the same page and they are found when I search the GRO index.

Any ideas why she might not be in the GRO index?

[Footnote: She appears to be illegitimate and is

subsequently described as a child of her grandparents in censuses. Her

grandmothers will reveals her true identity. I did

spot a Mabel Platt on the same page when I looked on FreeBMD

and a quick search for her on Ancestry didn't come up with any further matches.

She does appear in a GRO index search but with no mothers maiden name. Is it possible she is in the

indexes twice under different names? If I order the birth certificate using the

details I have above, even though a search doesn't return a match, am I likely to

receive it and will I be charged if they can't find it?]

I’m

sure that when you read that footnote you had the same thought as I did – that perhaps

Mabel Platt and Mabel Cannon were the same person (full marks to the member who

posted the query for including this additional information).

When

something like this occurs it’s often helpful to weigh up the odds of it

happening by chance: if you search the birth indexes for the forename ‘Mabel’

in 1873 you’ll find that there were only 32 in the whole of Cheshire that year,

and just 2 in Nantwich, ie Mabel Cannon and Mabel Platt.

How likely is it that both these entries would be on the same page in the GRO

birth register?

There’s

an additional clue. If you search at FreeBMD for

entries on the same register page you’ll get this list:

To

the untrained eye what leaps out from that list is the two Barker girls at the

top, possibly identical twins. But if you know a little about the GRO birth

registers you’ll soon realise that there are 11 names listed, when there’s only

room for 10 entries on a single register page – and that hints at the

possibility that there are two index entries for the same register entry.

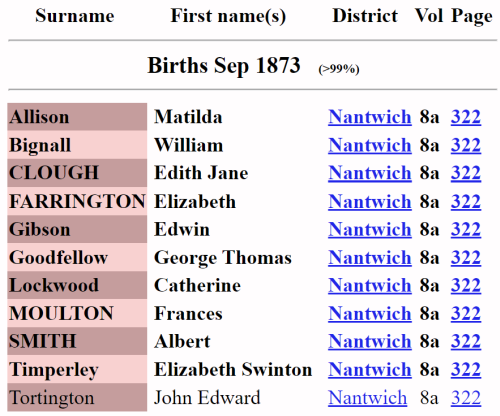

Sometimes

entries are mistranscribed, and if it’s the page

number which is wrong this can cause confusion – as you’ll see if you repeat

the same search for entries page 322:

Fortunately FreeBMD aim to

transcribe each entry twice, and the chance of two different transcribers making

the same error is fairly low. Entries shown in bold have been transcribed twice

– and if you look at the image of the page from the quarterly birth index for John

Edward Tortington, the one entry that isn’t bolded,

you’ll see that the page number is not 322 but 327 (I’ve already reported the

error to FreeBMD).

Something

to bear in mind is that Ancestry’s GRO indexes up to 1915 were provided by FreeBMD, so if you want to check another source, try Findmypast

or The

Genealogist. Findmypast is my preferred source for births

because they have added the mother’s maiden name for most of the entries from

1837-1911, and for this reason it’s a good place to start your search even if

you don’t have a subscription.

Tip:

it’s natural to make a beeline for the site(s) where we have a subscription, but

sometimes searches at free sites such as FamilySearch, or free searches at commercial

sites such as Findmypast will work better.

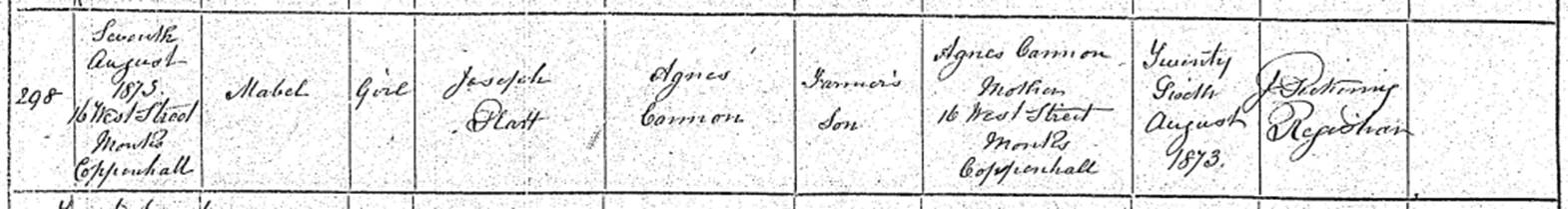

But

if you’ve read down this far I suspect you’re wondering if there is a happy

ending to the problem of Mabel. And there is – this is the entry from the GRO

birth register:

Whether you’re ordering

certificates or PDFs, or simply using the civil registration indexes to gather

freely available information, it’s important to understand how they were compiled,

and to recognise the differences between the contemporary quarterly indexes and

the GRO’s modern indexes.

Tip:

sometimes the fact that an entry has been recorded differently in the new

indexes tells us all we need to know!

What do the GRO references mean?

If

you’ve ever ordered an historic birth, marriage, or death certificate from the

General Register Office you’ll know that the numeric references you used to

order the certificate (volume and page) don’t appear on the certificate itself.

That’s because those references didn’t exist at the time the event was

registered – whilst there will be a sequential number in the first column, this

will relate to the original register, ie

the one at the church or register office.

The

registers held by the GRO contain copies of entries in the registers held

locally – that’s why you’re unlikely to see your ancestors’ signatures on a

marriage certificate ordered from the GRO. From 1837, when civil registration

began in England & Wales, loose leaf copies of the entries in the locally

held registers were submitted quarterly to the GRO, where the

pages were bound into large volumes with entries from other registration

districts, and the pages subsequently numbered sequentially.

In

other words the references we see in the quarterly indexes are the number of

the volume in which the entry can be found, and the number of the page on which

it is recorded.

Note:

the number of entries per full page varied over the years – a good way to check

how many entries there usually were in a particular quarter is to carry out a number of searches by page number.

How

were the indexes compiled? As I understand it, clerks at the GRO wrote out a

slip of paper for each birth or death, and two for marriages, which included all

the information required for the index, including the registration district, volume,

and page number. These were then sorted into strict alphabetical order, then

copied again to create the relevant index.

So

what we see in the quarterly indexes had been copied at least three times –

more if the original handwritten indexes deteriorated to the point where they

had to be replaced by typewritten or printed copies. It’s remarkable that there

are so few errors and omissions!

If,

like me, you searched for your ancestors’ marriages at the Family Records

Centre, or one of its predecessors, you’ll know how frustrating it was that prior

to 1912 the quarterly marriage indexes didn’t give the spouse’s surname. If you

had a clue to the spouse’s surname you could look up the entries for that

surname and scan them for a matching entry, ie one with the same volume and page references, but it

was infinitely more challenging if you didn’t.

However,

once the entries had been computerised – by FreeBMD

and others – it was possible to sort the entries by page number, so that there

would be only a handful of options (there was a maximum of 4, later 2,

marriages per page, but many pages were incomplete). And that’s how some sites are able to suggest who the spouse may have been, even for

marriage between 1837 and 1911.

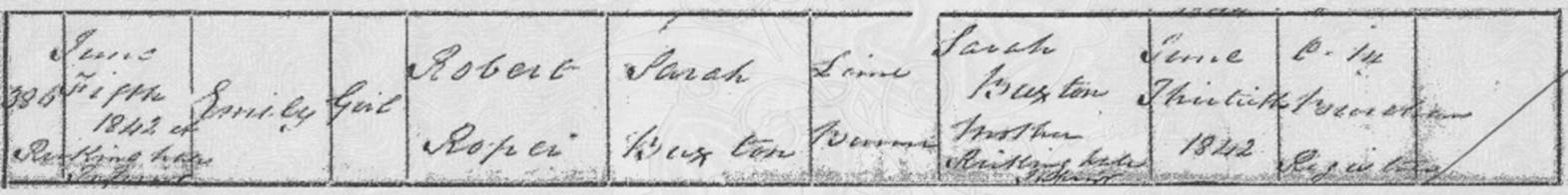

The first time I knocked down a ‘brick wall’ using DNA

When

I give a talk on DNA, if time permits I demonstrate to the attendees how I

knocked down my first ‘brick wall’ using DNA. It was a ‘brick wall’ that had

blocked my path for 15 years, yet some people might not have considered it a ‘brick

wall’ at all – since my great-grandmother’s birth certificate named her supposed

father.

When the birth

of my great-grandmother, Emily Buxton, was registered in 1842 her father and

mother weren’t married – at least, not to each other. Sarah Buxton (née Hunt) was

a young widow and, as for Robert Roper, all I knew was his name and occupation.

Even if the information on the birth certificate was correct, there was no

Robert Roper in the 1841 Census who was a lime burner, nor was there anyone in the

1851 Census who seemed a likely candidate, even allowing for the possibility

that he had changed his occupation.

Did

Robert Roper really exist? I certainly had my doubts, because Sarah Hunt too was

conceived and born outside marriage, and when Sarah eventually remarried in

1850 the name she gave for her father also seemed to have

been invented. And that’s how things remained until 2017.

I

had originally taken a DNA test in 2012, long before Ancestry started selling

them in the UK, and for the first 5 years DNA had proven an expensive

disappointment. In 2017 I bit the bullet and tested again – this time with

Ancestry. Within weeks I had matches with genetic cousins in the US who were descended

from a Robert Jeffreys Roper of Suffolk.

This

Robert Roper was also missing from the 1841 Census, but in 1851 he was shown as

a farmer of 170 acres with a wife and three teenage sons – hardly a likely

candidate, one would think. But the baptism entries for his sons (which were

not online) show that in the 1830s he was a lime burner – and taken together

with the DNA evidence, this proved beyond reasonable doubt that he was my

great-grandmother’s father.

With

the benefit of hindsight this wasn’t a ‘brick wall’ that was completely impossible

to solve using conventional methods, but there was no way of knowing that in

advance – and without the confirmation provided by DNA I would have been

relying completely on Sarah Buxton’s assertion that the father of her

illegitimate was a lime burner named Robert Roper.

DNA

isn’t a replacement for records-based research – it’s an extra tool in the researcher’s

toolbox, one that can:

· provide confirmation that the records are

correct;

· point us in the right

direction

when the records are elusive;

· prompt us to think

again

when the relevant records are wrong or misleading; and

· bridge the gap when the records are

missing

Save 25% on Ancestry DNA tests in the UK ENDS MONDAY

When

the records are missing, incomplete, misleading, or simply hard to find DNA is

usually the answer - and without a doubt testing with Ancestry was one of the

best decisions I ever made.

I’ve

not only knocked down numerous ‘brick walls’, I’ve been

able to confirm that my records-based research is correct – which is a much

under-rated benefit of testing.

If

you’re in the UK you can save 25% on Ancestry DNA until

midnight on Monday. Please click the banner below so that you can support LostCousins:

Ancestry.co.uk (UK only) – Ancestry DNA

reduced from £79 to £59 (plus shipping) ENDS 3RD APRIL

I

recently came across this fascinating page

on Rootsweb which describes the laws and customs in

Virginia, both before and after independence from Britain. Even if you don’t

have any colonists in your tree, reading it might prompt you to ask questions

about the laws and customs in England.

Note:

I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the information, but it appears to have been

compiled with care.

From family history to pioneer history

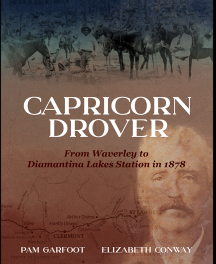

LostCousins

member Pam Garfoot has written a book with a difference

– so I’ve asked her to tell you about it:

My sister,

Elizabeth, and I have been passionate family history researchers for about the

last fifteen years. Family history research, as most readers are probably

aware, can take up a huge amount of time. But something else has kept us quite

busy for the last few years - another project which has been a logical flow-on

from our family history research.

Way back in

2017 we discovered by chance the existence of a diary handwritten by someone a

few generations back in our family tree (in fact, the brother of our great,

great grandmother). It was held in the special collections area of the James

Cook University in Townsville, Queensland. As far as we know, no-one had

studied it closely before. We made it our business to investigate.

We discovered

that the diary was a record made by Edward Hayes Talbot in 1878 during the course of a four-month  journey

droving cattle from the coast of Queensland (Waverley Station, near St

Lawrence) a thousand miles to the west (Diamantina Lakes Station in the Channel

Country). Droving (that is, moving

livestock overland from one outback location to another) was challenging work.

Droving trips often covered vast distances, with the droving team going on

horseback and the camp cook usually making the trip in some sort of dray or cart.

On this trip Talbot travelled with a handful of other men and even the wife of

one of them.

journey

droving cattle from the coast of Queensland (Waverley Station, near St

Lawrence) a thousand miles to the west (Diamantina Lakes Station in the Channel

Country). Droving (that is, moving

livestock overland from one outback location to another) was challenging work.

Droving trips often covered vast distances, with the droving team going on

horseback and the camp cook usually making the trip in some sort of dray or cart.

On this trip Talbot travelled with a handful of other men and even the wife of

one of them.

Determined to

write something about the journey, we researched the route travelled, the

places visited along the way, and the drovers and other people

involved. In many ways we utilised the research skills we had developed while

doing exhaustive family history research.

In 2020, the

diary was one of several items in James Cook University’s collection chosen to

help celebrate 50 years of the university’s existence. The ‘50 Treasures’

exhibition was the result and you can see a sample page from Edward Talbot’s

diary here.

Nearly six

years after we came across the diary, our book Capricorn Drover has been published. It tells the story of the

trip, the challenges faced, the places along the way, and the story of each

person involved. The book includes more than 80 black and white images and a

detailed route map. We are so excited to have been able to delve into some

fascinating Queensland pioneer history.

Further

details about the book can be found here

Thanks,

Pam – this is part of Australian history that I knew nothing about.

Wartime ration books discovered in cupboard

I

missed this story

about wartime ration books when it was reported in 2015 – I suspect quite a few

readers of this newsletter have made similar discoveries.

Note:

you can share photos of ration books, ID cards, and other ephemera with other

LostCousins members via the LostCousins Forum. If you’re not yet a member check your My Summary page to see whether you qualify for

membership.

Forced adoption

There

was a story

on the BBC News site this week about forced adoption in Britain in the 1950s,

1960s, and 1970s. As someone who worked for the Children’s Department of a

local authority in the late 1960s I was surprised to read the article – at that

time I was not aware of mothers (or parents) who were able to look after their

children being forced to give them up for adoption, though no doubt some single

mothers may have felt under pressure to do so when the practical difficulties of

bringing up a child on their own were explained to them.

Note:

until fairly recently the term ‘orphan’ described a

child who had lost one parent, not both – this underlines the fact that few single

parents could bring up a child and earn a living.

It’s

certainly true to say that moral standards were higher in those days, and that

those who didn’t live up to those standards were looked down on, but that’s not

quite the same thing. If anything it was society that

forced some mothers to give up their children, rather than the government – I

suspect that fathers of single mothers were often unsympathetic.

Did your ancestor work on the railways?

The

Railway Work, Life & Death project has just released a new dataset, featuring

details of around 25,000 British and Irish railway trade union members and how

their union looked after them between 1889 and 1920.

The

project looks at accidents to railway staff before 1939, transcribing and summarising

details from railway records. Together with the existing data, the database now

covers nearly 50,000 individuals, all transcribed by the project's excellent

volunteers.

The

new trade union records come from the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants/

National Union of Railwaymen, and tell us about

support in the event of accident, ill-health, or old age. They show how the

Union provided financial benefits for members and their families,

and represented their interests at coroner's inquests. The project is a

joint initiative of the University of Portsmouth, the National Railway Museum and the Modern Records Centre at the University of

Warwick, working with The National Archives. They want to see the information they’re

making available being used by you, in your research – it's all available free in

a spreadsheet that you can download from the project website.

Note:

they're also keen to hear from you if you find someone you're researching, so do

please let them know.

Roll over Beethoven

Everyone

knows that Beethoven started losing his hearing in his 20s,

and was almost totally deaf in his 40s – but only now have researchers attempted

to analyse his DNA in order to find out why.

Don’t

worry, they didn’t have to exhume his remains – they had access to 8 hair

samples from different sources, and as DNA tested proved that 5 of them came

from the same individual, they used those samples for their further analysis.

Whilst

they were unable to find a definite cause of his hearing loss, they were able

to gain some insight into what killed him – see this BBC article

for more details.

Interpreting Scottish handwriting for the 16th

and 17th centuries FREE

National

Records of Scotland has a free PDF guide to help you interpret the handwriting

in Scottish documents from 1500-1700 – you can download it here.

Why

did BBC announcers wear dinner jackets – on the wireless?

It’s

well known that announcers on the BBC wore dinner jackets when they were reading

the news on the radio in the 1930s, but this is a rather misleading

interpretation of the evidence, according to this interesting article I found online. The

official

version is rather different…..

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2023 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!