Newsletter – 23rd July 2025

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire parish registers online NEW

Voting age in England & Wales to change for the first time since 1969

Essex teenager “living in the 1940s”

Are 3-parent children a genealogical nightmare?

Stolen historical documents found in attic

Why the 1861 and 1871 Irish censuses were destroyed

Case study: Searching for Miss Henningwright

Review: The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland

Who Do You Think You Are? offer

Stop Press UPDATED

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue (dated 15th July) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire parish registers online NEW

The parish registers for Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire are now online at Ancestry and, because they have been scanned in colour, they’re not only a delight to look at they’re much easier to interpret than microfilmed images. There are over 4 million transcribed records already online and linked to the respective images: ultimately there will be closer to 6 million records.

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1950

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1997

Baptisms from 1813 onwards are not yet shown in the Card Catalogue and I suspect that they are still being transcribed, but you can nevertheless access what is available using the link below:

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1924

To the best of my knowledge I don’t have any ancestors from these counties so I’m not the best person to check the quality of the transcriptions, but I understand that Ancestry have licensed transcriptions from Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire Family History Society, so that is a positive indication.

It’s worth noting that 5 years ago Ancestry made available electoral registers and similar records for Cambridgeshire:

Cambridgeshire, England, Electoral Registers, Burgess Rolls and Poll Books, 1722-1966

Apologies to anyone who had hoped to attend last Wednesday’s free Zoom talk on manorial records organised by Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire Family History Society, but was unable to book a place.

Although it was open to all, the organisers hadn’t expected it to be advertised so widely – it was not only mentioned in my last newsletter but also in at least one of the major family history magazines – so it’s understandable they were overwhelmed by the response.

Voting age in England & Wales to change for the first time since 1969

I qualified to vote in 1969 – not because I had a significant birthday, but as a result of the implementation of the Representation of the People Act, 1969. The UK was the first country to lower the voting age to 18 (although it wasn’t until 1970 that 18 year-olds had an opportunity to vote in a General Election, and they weren’t able to stand for Parliament until 2006).

Note: if you would like to know more this 2021 academic article (in PDF format) explains the background to the 1969 change.

Two years ago the minimum age for marriage in England & Wales increased to 18; it remains at 16 in Scotland and Northern Ireland, although there were, at one point, plans to increase it to 18 in Northern Ireland (which would have brought it into line with the Republic of Ireland, which does not recognise marriages under 18).

The UK government has now announced that the voting age will be reduced to 16 in the whole of the UK before the next General Election, which is expected to be in 2029 – if this goes ahead children who are currently 12 years old will be able to vote in four years’ time. (Voting age for Scottish elections was reduced to 16 with effect from 2016.)

For genealogists the contemporary Electoral Register is an important source of information – even though it has long been possible to opt out of the ‘open’ register, the version that is available for purchase. At Findmypast you can search modern Electoral Registers for the whole of the UK, although – because of the opt-out only the 2002 data can be regarded as anywhere complete.

UK Electoral Registers & Companies House Directors

A surprisingly high number of people are still living where they were in 2002 – once you have found a relative in 2002 you can check whether the property has been sold since then by typing the postcode into Google and choosing the Rightmove link. Online property agents have access to Land Registry records of sales, and if a property hasn’t sold since 2002 it’s quite likely that it is still owned by the same family. (Of course, this doesn’t help much if the relative you’re searching for was in rented accommodation in 2002.)

Note that both Ancestry and Findmypast have collections of older registers, and these aren’t just confined to the UK.

Essex teenager “living in the 1940s”

My first bicycle was a pre-war delivery bike with a basket on the front: I was about 6 years-old, had never ridden a bicycle before, and rode it straight into the lamp post outside our front gate – hardly an auspicious start! My first football boots could well have dated from the 1920s, they were so old (if you ever saw the cartoon strip Billy’s Boots – which featured in Tiger in the early 1960s and was revived in Scorcher in 1970 – you’ll know what I mean).

We didn’t have a fridge, a washing machine, or central heating – but there were a lot of people worse off than we were. We did at least have running water and an inside toilet – and I had my own room until my little brother came along. After the Coronation in 1953 we had a rented black and white television with a 12in screen which could not only receive BBC, but also ITV when it launched in 1955.

After we moved house in the late 1950s my father bought a ‘radio stereogram’ on the never-never (the purchase price of around 85 guineas was many times his weekly wage) and he passed on to me his old gramophone with a supply of metal needles, as well as his modest collection of 78s – I must have played Alexander’s Ragtime Band hundreds of times! I thought of myself as lucky – the previous generation would have had to make do with a hoop and a stick – but I’m not sure that the youngsters of today would be satisfied by such primitive pastimes.

So I was a little surprised to read this article about a 16 year-old boy from Colchester, Essex who lives as if it’s the 1940s. Don’t get me wrong, if I could get hold of some of the Fair Isle pullovers that Tristram wears in the remake of All Creatures Great & Small I would happily add them to my wardrobe, but I do wonder where it is all leading?

Just as I was finalising this newsletter I noticed an article on the BBC News site which was headed 'A hospital gave us two death certificates for dad to cover up their mistake'. According to this page on the GOV.UK website, once issued a death certificate cannot be amended but under certain circumstances a note can be added to the register entry.

On a closer reading of the news article, it seems that the family of Brian Holmes (the deceased) were not referring to death certificates issued by the local register office, but the medical certificate of cause of death signed by a doctor at the hospital where Mr Holmes died in 2019.

What you won’t discover by reading that article is that the system changed significantly in September 2024: all deaths in any health setting that are not investigated by a coroner are now reviewed by NHS medical examiners. The principal function of a medical examiner is to scrutinise the medical certificate of cause of death prepared by attending practitioners (you can find out more about the new system here).

Are 3-parent children a genealogical nightmare?

I’m sure you’ve read the news that 8 healthy children have been born in the UK thanks to a technique which enables the mother’s faulty mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) to be replaced with that of a donor. This page on the website of Boston Children’s Hospital gives details about mitochondrial diseases and the limited treatments available, if you can bear to read it.

Despite years of research there are no cures for diseases caused by faulty mitochondria, so this technique – which I first wrote about in 2012 when the UK government initiated a public consultation – is literally a lifeline for mothers who are carriers of faulty mtDNA. This BBC article, also from 2012, tells the sad story of Sharon Bernardi – who had lost ALL of her children to mitochondrial diseases. If you have a Findmypast subscription you can click here to see a photo of Sharon and her husband Geoffrey on their wedding day in 1986 and here to see the death notice for their son Geoffrey, who died aged just 30 hours in October 1987.

You would think that since three people are contributing DNA this technique could create problems for the genealogists of the future, but fortunately mtDNA is of relatively little use to genealogists: because mtDNA mutates so slowly there are only rare circumstances in which it can provide useful information about our ancestry. It’s much more likely that DNA tests are confused by bone marrow or stem cell transplants – which is why, when you register an Ancestry DNA kit, you’ll be asked if you have ever had such a transplant.

Note: you’ll find lots of helpful information about the process of registering an Ancestry DNA kit (for yourself or somebody else) here.

Stolen historical documents found in attic

So many of the documents we’d like to view have been burned or pulped that it’s particularly annoying to discover that the only reason some are missing is because they have been stolen.

Around a decade ago 25 priceless documents were removed from the Dutch National Archives, in the Hague – these included 16th century government documents and records of the Dutch East India Company. According to this article in Smithsonian Magazine the documents were discovered by a relative in the attic of a deceased former employee of the National Archives.

Some vicars regarded parish registers as their personal property and kept them when they retired, or moved to another parish. It’s possible this might explain why the 18th century registers for Althorne in Essex are missing – starting in 1795 the parish of Althorne was gradually merged with adjoining Creeksea to form a single benefice.

Why the 1861 and 1871 Irish censuses were destroyed

So many Irish records have been lost for one reason or another that it’s difficult to remember what happened to a particular set of records. However in the case of the 1861 and 1871 Censuses we are fortunate to have a record of what was said at Westminster on 29th September 1909 in response to a parliamentary question:

Mr. SLOAN

asked the Postmaster-General if he can state under whose instructions and for what reason the Census Returns of 1861 and 1871 have been destroyed, while the Returns of 1841 have been preserved, and are now used to verify the ages of State pensioners?

Mr. BIRRELL

My right hon. Friend has asked me to answer this question, which appears to relate to the Irish Census Returns. I understand that the destruction of the Returns for 1861 and 1871 was authorised many years ago by the Irish Government, as they could not be treated as Public Records, in consequence of an undertaking given on the householders' forms to the effect that the information would be published in general abstracts only, and that strict care would be taken that the Returns should not be used for the gratification of curiosity or for any other object than that of rendering the Census as perfect as possible. No such undertaking was given in connection with the Census Returns of 1841 and 1851 now in the Public Record Office. Before authorising the destruction of the Returns in question, the Irish Government ascertained that the Householders' Returns in connection with the Census of Great Britain in 1841, 1851, 1861, and 1871 had been destroyed.

However, whilst in England & Wales the household schedules had been copied into summary books by the enumerators, the procedure had been different in Ireland, according to the Central Statistical Office. On the other hand it’s likely that even if the household schedules had survived they would have been lost in the 1922 fire which destroyed the 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851 returns.

The earliest surviving complete censuses of Ireland are 1901 and 1911, which had presumably not been transferred to the Public Record Office in Dublin. But what happened to the 1881 and 1891 censuses – why were they not destroyed in the fire? It turns out that they were pulped in 1918 – though it’s not clear whether this was because of a wartime paper shortage, or whether the decision was based on the same flawed thinking that led to the destruction of the 1861 and 1871 returns.

Where they have survived, censuses are an incredibly valuable source for family historians – not least because they have birthplace information, which may well be the only clue to an ancestor’s origins. Even if they lied about their age or marital status, or were recorded under a different name, most people gave what they believed to be their correct birthplace.

Unfortunately genealogy isn’t a priority, or even a consideration, for the public bodies that run censuses – and the 1951 Census was the last British census to include precise birthplace information, so this information has only been recorded for a fraction of the current population (I only sneaked into the 1951 Census by a matter of months). If 2031 is going to be the last time that everyone in the country is recorded in a census, surely it’s important that we collect basic information such as place of birth? It’s regarded as sufficiently important to be shown on my passport – shouldn’t my place of birth also be recorded in the census?

In Scotland the census is run by National Records of Scotland, on behalf of the Registrar General for Scotland: they have already launched a consultation on the 2031 Census, to which members of the public can contribute – you can find out more here. In England & Wales the consultation will be launched this autumn – I’ll let you know when it begins.

Case study: Searching for Miss Henningwright

LostCousins member Mike, in Sydney, sent me this fascinating account of how he cracked a thorny problem in his family tree….

Hello Peter,

you often encourage us to work at knocking down our “brick walls’, including the method, among others, of walking away, leaving it alone and coming back with a fresh mind and approach. And so it was with one of my maternal great-grandmothers.

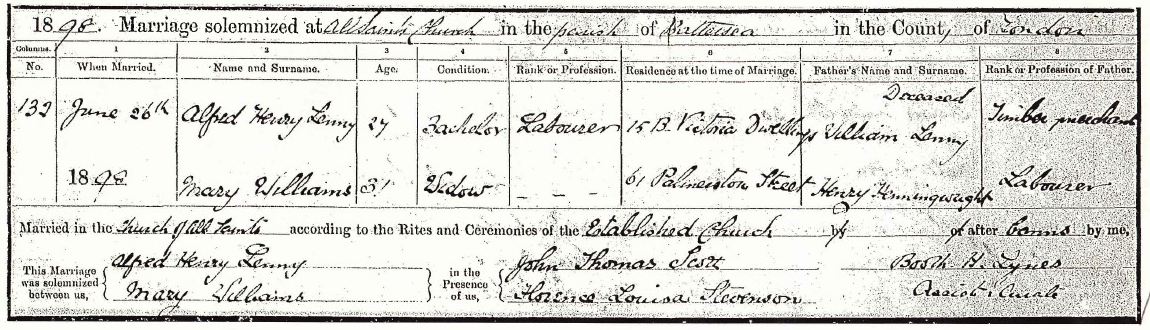

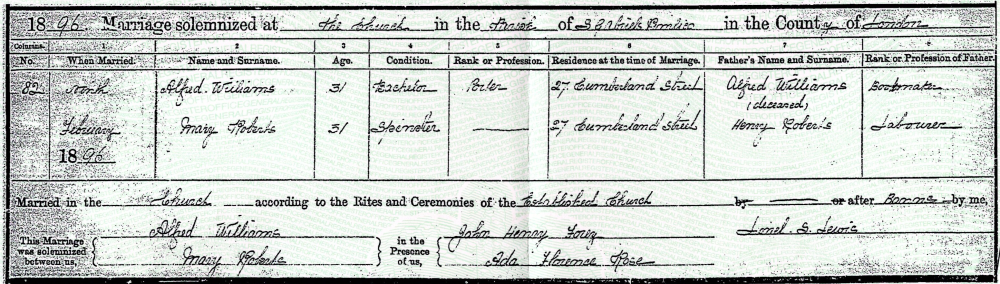

I knew my mother’s paternal grandfather was Alfred Henry Lenny (15 Oct 1872 - 16 Dec 1954), born illegitimately in Ipswich and raised by his grandparents, perhaps not welcome in his mother Elizabeth’s eventual family once she married. In the mid 1890’s he moved to London and by 1898 was living in Battersea. On 26 June that year he married Mary Williams, a widow, whose father is listed on their marriage certificate as Henry Henningwright (a most unusual name – surely easy to trace).

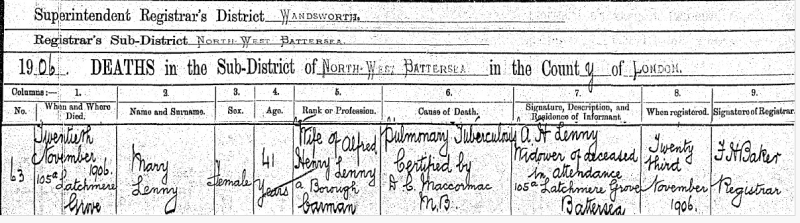

However, the surname Henningwright does not appear to exist. I checked births, baptisms, marriages, deaths and burials in Ancestry, Findmypast and the GRO Indexes and there were none anywhere in England at any time, past or present. A look at her death registration from 1906 provided no help. I parked this problem for a couple of years.

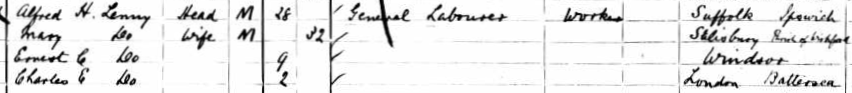

The next step was the 1901 Census. There, Mary was born in the Parish of Wishford, (a few miles NW of) Salisbury. Wishford refers to the village of Great Wishford. Ancestry now has good coverage of this part of Wiltshire in its parish registers. I also noted there was a nine-year-old son, Ernest C, who was obviously from her previous marriage. The second child, Charles E, is my grandfather.

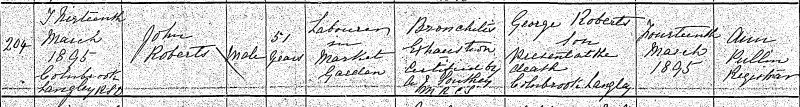

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

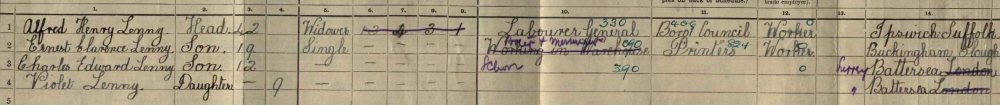

So, I assumed he would be Ernest Williams. OK – don’t assume. No Ernest Williams. Still he was listed as being born in Windsor. Or was he? The 1911 Census suggested otherwise.

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

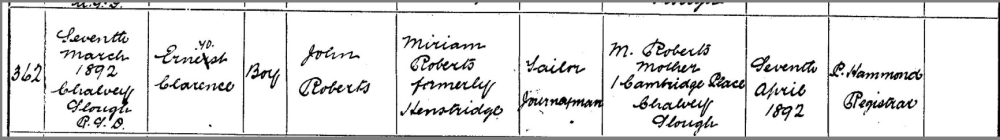

OK – Slough, that’s near Windsor, sort of. It also gave the full name of Ernest Clarence. A search by those first names and birthplace Slough for 1892 then identified Ernest Clarence Roberts in the Eton registration district – between Windsor and Slough.

My next step was to use the GRO Index and this birth gave me the mother’s maiden name – Henstridge. So with the £3 digital image option, I retrieved his birth register entry:

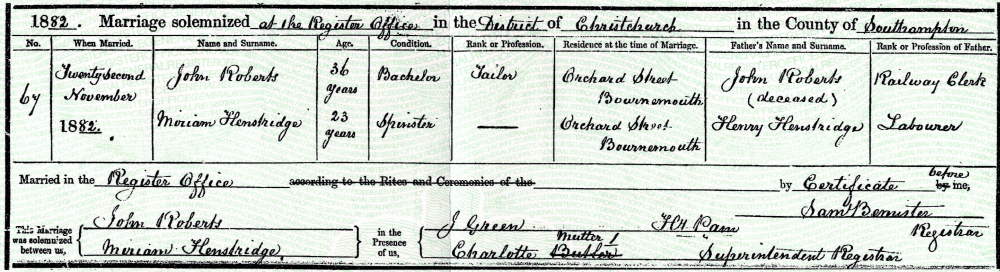

This also showed that ‘Mary’ was originally Miriam Henstridge. At last I was able to identify Miriam Jane Henstridge, born 2nd March 1863 in Great Wishford, Wiltshire. That all made logical sense. But to confirm, I purchased certificates for her first two marriages:

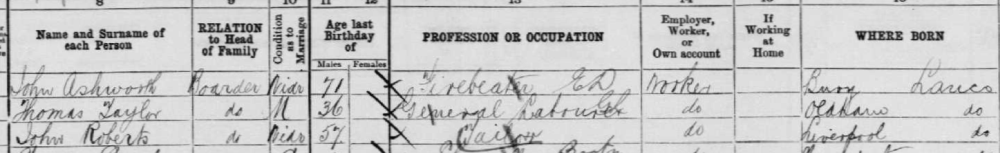

These show Miriam (Mary) was a bit liberal with her age, overstating it from 19 to 23 at her first marriage and understating it to 31 at her second. The obvious errors in the second may have been her or the Minister – spinster vice widow and her father’s surname. I can imagine the Minister’s question – “Father’s name?”, answer “Henry”. Right – so must be Henry Roberts as I have assumed or been told you are a spinster. But I accept it is the right person as the first name and occupation are correct.

So now that Mary Henningwright has become Miriam Jane Henstridge, I have been able to take the Henstridge line around Great Wishford/South Newton/Stoford and Downton in Wiltshire back another four generations to the first half of the 18th century and still working. Mind you, the research is made even more difficult by the number of inter-marrying cousins from the Henstridge/Shergold/Blake/West/Down/Martin families!

My lessons learned:

· Keep track of new uploads of data to the major family history websites. I don’t believe the necessary Wiltshire parishes were in Ancestry when I first looked.

· Census data is excellent. I only cracked this through working out who Ernest Clarence Lenny (1911 Census) was.

· Remember that widows use their recent married name on marriages, not their maiden names. Three marriages make it even more confusing.

Well done, Mike. Another lesson is that sometimes you can only unravel your direct line by researching collateral relatives, typically siblings (or in this case, a half-sibling).

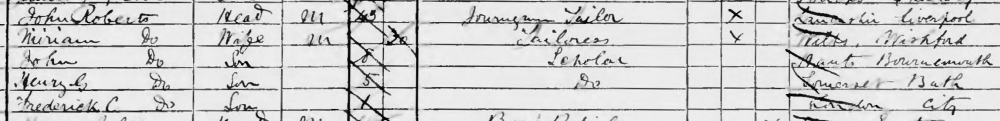

Re-reading what you had written got me wondering whether Mary/Miriam was being deliberately deceptive when she remarried in February 1896? Might she have been trying to disguise the fact that her first husband, John Roberts, was still alive? He was certainly alive at the time of the 1891 Census:

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

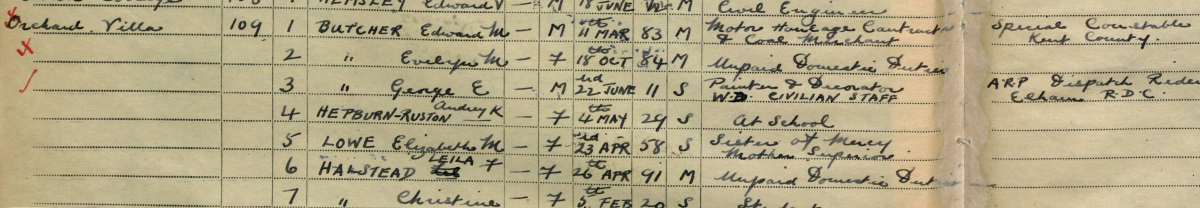

So I looked for a John Roberts of around the right age whose death had been registered in Eton registration district or the surrounding area between 1891 and early 1896. There was only one, and it seemed to fit perfectly:

![]()

Well, it seemed pretty convincing. But, just to make sure, I invested £3 for the death register entry:

Uhuh…. definitely NOT the John Roberts who was a tailor in 1882 and 1891. Unfortunately it’s too common a name to examine every possible death, so I tried a different tactic – trying to prove that he hadn’t died by finding him in the 1901 Census:

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

This John Roberts is in Oldham in 1901: the age is about right, the birthplace agrees with the 1891 Census, and he’s in the same profession. He’s shown as a widower which indicates that he has been married – and it’s what you’d expect him to say if his previous marriage had broken up. Without further research it’s not possible to be certain whether Mary/Miriam committed bigamy or not, but it just shows how solving one mystery often leads to another. Over to you, Mike!

Until the end of July you can save 30% on 6-month subscription to Newspapers.com – part of the Ancestry family. With over 1.1 billion pages in the collection it’s probably the biggest online newspaper collection there is, and whilst it is US-orientated there are over 100 million pages from British and Irish newspapers.

To take advantage of this offer please click the banner above, or – if you can’t see the banner – click his link.

Note: you may be charged tax in addition to the price quoted – but you’re still saving 30%.

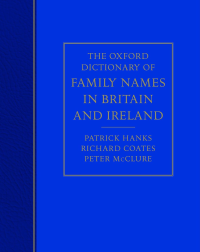

Review: The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland

The most

comprehensive book of its type, The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in

Britain and Ireland was far too expensive for individuals to buy when it

was released in 2016 – the four-volume hardback edition ran to well over 3000

pages and cost an incredible £400, so it was clearly aimed at libraries. Even

the Kindle version cost £260.

The most

comprehensive book of its type, The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in

Britain and Ireland was far too expensive for individuals to buy when it

was released in 2016 – the four-volume hardback edition ran to well over 3000

pages and cost an incredible £400, so it was clearly aimed at libraries. Even

the Kindle version cost £260.

Fortunately my local library had a subscription to the online version, so I was able to look up the surnames of interest to me from the comfort of my own home, and it proved incredibly useful – especially for some of the rarer surnames, and those with many spelling variants.

Then, just last week I discovered that the price of the Kindle version at Amazon.co.uk had plummeted from £260 at release to just £0. You read that right – I was able to download the Kindle version for no cost whatsoever!

However, because it’s a Kindle book I can’t confirm whether it’s free in other territories – I fear it may not be, but all you have to do to check is click the relevant link below:

Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.ca Amazon.com.au

Tip: just a reminder that you don’t need a Kindle device to read Kindle books – you can download the Kindle app for whichever device you already have, whether it is a phone, a tablet, or a computer.

Sum of Us by Georgina Sturge is proving to be a fascinating read – I bought a hardback copy after reading an article by the author in the latest issue of Significance (published by the Royal Statistical Society in association with the American Statistical Association and the Statistical Society of Australia).

As a statistician at the House of Commons Library she has an enviable amount of information at her fingertips, and it certainly shows. She’s also got some useful connections – she was able to get Audrey Hepburn’s entry in the 1939 Register opened (because the actress died in Switzerland her death hadn’t previously been linked to the closed record in the register):

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

Funnily enough I came across Audrey Hepburn’s name a couple of days ago when I was looking into the novels of Henry Cecil, the judge whose best known work was probably Brothers In Law (Ian Carmichael starred in the film, Richard Briers in the TV series). Apparently Alfred Hitchcock wanted to make a film of No Bail for the Judge starring Audrey Hepburn, but it never came to fruition.

Back to the book: I’m currently reading Chapter 4 (out of 15), so still some way to go – but it’s certainly crammed full of interesting facts and statistics. I think the author goes a bit too far in saying that the 1939 Register was ‘instrumental’ in the creation of the NHS and the Welfare State, but there’s no denying that – because the register continued to be updated after the war – it proved to be a very useful way of keeping track of patients.

A paperback version is due for release in April 2026 at £10.99, but if you’re quick there’s a used hardback copy in very good condition at Amazon UK for around £15 including shipping, which is £5 less than I paid last week for my copy (the full price is £25).

Who Do You Think You Are? offer

If you live in the UK you can get 6 issues of Who Do You Think You Are? magazine for just £11.99 when you follow this link.

I’ve been reading it ever since issue 1 (way back in 2007), and I’ll typically tear out 15 or 20 pages, then sort them thematically for future reference (which is why I don’t get on with digital versions of magazines, although I can get many of them free through my local library).

Good news for anyone with Suffolk ancestors - Suffolk Archives have posted an update on their website announcing that the registers will be online at Ancestry from 14th August. And if you're in the US, there's a flash sale on DNA kits - see the advert below. In effect it ends on Sunday - especially if you're on the West Coast.

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2025 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links – if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins (though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser, and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!