Newsletter – 29th August 2025

Half-price Findmypast subscriptions EXCLUSIVE OFFER – SAVE £100

What makes Findmypast different – and why does it matter?

Registration of births in the 21st century

Patrilocality and female exogamy

Stop Press UPDATED

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue (dated 20th August) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

Half-price Findmypast subscriptions EXCLUSIVE OFFER – SAVE £100

Which subscription site is the best? Ultimately it all comes down to you: it’s about where your ancestors lived and what period you are researching. For me, with ancestors from 10 English counties (plus London, Ireland and Germany), and multiple ‘brick walls’ in the 1600s and 1700s there is no one site that meets all of my needs – and I’m willing to bet that it’s the same for most people reading this newsletter.

But with subscriptions costing around £200 a year it can be tough to find the money for more than one – so when a half-price offer comes along it’s hard to resist, especially when the offer is EXCLUSIVE to readers of this newsletter.

(You can share a link to this newsletter with friends and family – but if they’re serious about family history, why not suggest that they join LostCousins so they can get their own newsletters in future?)

Earlier this year Findmypast had a half-price offer, the first I can remember since the spring of 2015 – when Findmypast didn’t have half the records that they do now. The 1921 Census is an obvious addition, but the 1939 Register wasn’t released until November 2015 (and even then it wasn’t included in subscriptions until the following year).

Also in 2015 Findmypast had yet to announce their ground-breaking partnership with the Roman Catholic Church, which has subsequently led to tens of millions of records going online for the first time – including the baptism of my great-great grandmother, whose birth wasn’t registered when she was born in 1840. That record was key to knocking down a ‘brick wall’ that had been blocking my way for almost two decades and, whilst DNA also played a part, both were essential to the solution.

There’s another reason why finding births is a lot easier than it use to be. In 2016 the GRO added a new birth index to their website, one that includes the mother’s maiden name as far as back as 1837 – the original indexes didn’t have this information until after 1911. It greatly reduces the chance of ordering the wrong birth entry, but sadly the GRO’s search is very limited in its capabilities – identifying all the children born to a particular couple can require 10 or more different searches!

Findmypast have added maiden names to most entries in their index of 58 million births from 1837-1911, so as a Findmypast subscriber you’re no longer constrained by the unnecessarily strict limitations of the GRO’s own search. This is a massive improvement, one that other sites ought to emulate – but haven’t.

These are just examples that I’ve chosen to emphasise how much has been added and improved. Which brings me to newspapers…..

In 2015 the British Newspaper Archive had a mere 10 million pages – now there are 95 million, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the 100 million barrier is broken in the next few months. All of these pages, with billions of names, are available through the Findmypast website and, thanks to a complete re-engineering of the search, it’s far easier to find what you’re looking for than it would have been 10 years ago.

Although this offer is exclusive to LostCousins, you won’t be supporting my work unless your purchase is tracked as coming from the LostCousins site – and that very much depends on which browser you use, what the browser settings are, and whether you have any software installed that has ‘privacy’ features. This could be an adblocking extension in your browser, your Internet security software, or a VPN. To maximise the chances of supporting LostCousins I recommend using the Chrome browser – if you haven’t used it before, the default settings are just fine.

Please ensure you use the correct link below when you make your purchase: if you start on one Findmypast site and end up on a different one the connection to LostCousins might be broken.

Findmypast.co.uk – SAVE 50% ON 12 MONTH ‘EVERYTHING’ SUBSCRIPTIONS

Findmypast.com.au – SAVE 50% ON 12 MONTH ‘EVERYTHING’ SUBSCRIPTIONS

Findmypast.ie – SAVE 50% ON 12 MONTH ‘EVERYTHING’ SUBSCRIPTIONS

Findmypast.com – SAVE 50% ON 12 MONTH ‘EVERYTHING’ SUBSCRIPTIONS

All Findmypast sites have the same records, and you can use whichever of their sites you prefer – even if you bought your subscription through a different site. Inevitably the 50% discount only applies for the first year, but annual subscribers to Findmypast get an automatic 15% Loyalty Discount on renewals, so that will soften the blow a little should you opt to continue after the first year.

This incredible offer is scheduled to end on Monday 1st September, but if it is extended (as I hope it will be) please continue to use the links above – they will still work. The same would apply if Findmypast are so delighted with the results that they decide to open the offer up to everyone: please continue to use my links (assuming you want to support LostCousins, of course!).

Should the offer be extended I’ll be back in touch on Monday, but you can also check for updates in the Stop Press section at the end of this newsletter.

Note: as it is designed to attract new subscribers, the half-price offer is not available to current Findmypast subscribers, but if you have a lesser subscription that is no longer on sale (such as the old Plus subscription) you might be able to upgrade on favourable terms. Try it and see.

What makes Findmypast different – and why does it matter?

One of the biggest mistakes that any family historian can make is to assume that all of the major genealogy websites have the same records, and that the same search techniques work equally well at every site.

Even highly-experienced researchers – as most LostCousins members are – often fail to appreciate that they can get better results by adapting their search technique. For example, when you’re filling out a Search form, do you enter as much information as possible, or as little as necessary? The first technique can work well at FamilySearch and Ancestry, where it often produces lots of results (though most of them won’t be relevant) – but at Findmypast you’ll generally get much better results if you enter less information (it also saves time!).

One of the things I like most about Findmypast is the way that they handle forename variants. You don’t need to tick the ‘include name variants’ box to allow for middle names and initials: for example, a search for ‘Marie’ will find ‘Marie-Claire’, ‘Marie Ann’ and ‘Marie J’. Similarly, a search for ‘Mary’ will find ‘Mary Ann’ (though not ‘Maryann’ or ‘Marianne’). When you do tick the ‘include name variants’ box you’ll get every result that might feasibly fit, including records where only initials are shown.

I also like being able to re-order the Search results by clicking the heading at the top of any column. I find this particularly useful when I’m looking for baptisms as I can sort them by date, by location, or by the forename of the father or mother.

But it’s not just about how you fill out the Search form and sort the results – there’s also the question of what records you’re searching, and how the records are organised. Ancestry typically organise records according to their source – so if parish registers for a single county are split between two or more record offices you might have to carry out multiple searches to find the records you’re looking for (assuming you realise what has happened).

By contrast, Findmypast bring together all the records they have for a particular county, so you don’t necessarily need to know which record office holds the registers. Sometimes there might be three or four results for the same baptism, all from different sources: this might seem like unnecessary duplication, but it greatly reduces the chance that you’ll miss an entry because it has been wrongly transcribed.

Similarly you can search marriages for a county without having to worry whether they took place before or after 1754, when new registers were introduced. To carry out the same search at Ancestry is much more complicated – especially since marriages between 1754 and 1812 won’t all be in the same record set (and what works for one parish might not work for another parish in the same county).

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that Findmypast have a large collection of transcribed parish records thanks to their excellent relationships with family history societies. You don’t need me to tell you that volunteers from family history societies are by far the best transcribers, thanks to their local knowledge and their diligence – this means that even if the parish register images are at Ancestry, you might find the entry you’re looking for more easily by starting at Findmypast.

Registration of births in the 21st century

Although the fundamental purpose of civil registration hasn’t changed since it was introduced in England & Wales in 1837, the gradual computerisation of the system has resulted in changes to the way that entries are recorded.

I’ve never registered a birth, but a 2019 response to a Freedom of Information request set out the system as it then was:

When a birth is registered the informant(s) provides the registrar with the required information. This is captured onto a system used by the registration service to complete the register page which is printed out for the informant(s) to check and sign. Once the informant(s) have checked that the information recorded is correct the register page is signed by the registrar to complete the birth registration entry. The signed birth registration entry, which is the primary legal record, is retained by the registrar in the birth register for that district and subsequently deposited with the Superintendent Registrar when the register is full.

The signature details (of both the informant(s) and registrar) are then transcribed exactly onto the system. This creates a digital version of the record from which a certificate can then be issued. All certificates, printed from this system, will only have a printed version of the signatures included in the registration.

The registrar or superintendent registrar (depending on who has custody of the registration) is required to sign all certificates that they issue. This is to confirm that the information held in the document is a true copy of an entry in their custody. This will be the only original signature on the certificate.

That description matches my experience in 2010 when my sister and I registered our father’s death: the procedures for registering births and deaths are broadly similar.

Keeping track of the procedures can be difficult because they are not only governed by primary legislation (ie Acts of Parliament) but also by secondary legislation, which tends to undergo less scrutiny and receive less publicity. For example, the registration of births and deaths in England & Wales is regulated by The Registration of Births and Deaths Regulations 1987 – the current version of which you can find here.

Just to complicate things the regulations have been modified numerous times since 1987 – and on several occasions since 2019, some prompted by the lockdowns in 2020 – so it’s quite difficult to follow the amended document. Perhaps the most interesting part is towards the end, where there are examples of the various forms – including some which most of us won’t have encountered.

It’s dangerous to rely on snippets shown in search results. Even if they seem to make sense, check the web page or document that the snippet has been taken from, to ensure that the words quoted haven’t been taken out of context.

Furthermore, the fact that something has written in an academic paper doesn’t guarantee that it’s correct. Check the source(s) that the author cites to ensure that they are actually relevant.

A PDF article I found online recently begins with these two sentences:

In England from the twelfth century until the early nineteenth century, incest was a matter for the church authorities alone. ‘Adultery was not, bigamy was not, incest was not, a temporal crime’, as Pollock and Maitland summed up the English legal tradition; ‘fornication, adultery, incest and bigamy were ecclesiastical offences, and the lay courts had nothing to say about them’.

Pollock and Maitland were writing in 1895, so you might reasonably assume that their scholarly work supports the opening of this 2002 article from the journal Past & Present (published by Oxford University Press and “widely acknowledged to be the liveliest and most stimulating historical journal in the English-speaking world”).

However, Pollock and Maitland were writing about an earlier period – their book is entitled The history of English law before the time of Edward I – and given that Edward came to the throne in 1272, it’s surely somewhat misleading to use the quote in an article which is focused on the 19th century?

According to Professor Probert, a source that I trust implicitly, bigamy was made a criminal offence punishable by death in 1604; as for adultery, there was a notorious civil case relating to ‘criminal conversation’ in 1769, and the Oxford English Dictionary cites a 1716 case.

To be fair, that 2002 journal article is primarily about incest and cousin marriage; the word ‘bigamy’ only appears in that quote. Nevertheless there is a danger that someone who reads those first two sentences – perhaps in their search results, or an AI summary – will get the wrong impression.

Patrilocality and female exogamy

The average English parish had only 500-1000 residents in the 1700s, and you might reasonably expect this to lead to a high proportion of marriages between cousins. However, that isn’t what I’ve found during my own research – and I think I know the reason why.

Whereas my male ancestors were mostly agricultural labourers, working-class girls often went into service – and this would usually continue until they were married. I can’t be sure which of my female ancestors worked as domestic servants, but I do know that most of them were born in a different parish from the one in which they eventually married. You might think that from 1754 onwards this would be evident from the marriage register, but if the bride was employed in the parish as a live-in servant she would be described as ‘of this parish’ irrespective of where she was born.

Couples tended to start their married life in the village where the groom’s family lived. It’s not a modern phenomenon: archaeologists have found extensive evidence of patrilocality and female exogamy going back thousands of years. But for genealogists it makes it even more difficult to research our female lines – for example, in Suffolk where a fifth of my ancestors originated, there can be as many as 100 parishes within a 10-mile radius, and multiple families with the same (or similar) surnames.

It’s no wonder that Findmypast found, when they analysed the trees of their users, that 70% of the unknown ancestors were female!

When I was growing up the phrase “What the Dickens?” was in common use – and I assumed until recently that it somehow related to Charles Dickens. Wrong! It turns out that it was used by Shakespeare more than two centuries earlier.

Growing up surrounded by the stories of Charles Dickens I was conscious of the fact that, in the early 19th century, many crimes which we would now regard as minor were punishable by death – stealing a handkerchief worth more than a shilling is an example that springs to mind. This article, on the Capital Punishment UK website, states that:

In 1688 there were 50 crimes for which a person could be put to death. By 1765 this had risen to about 160 and to 222 by 1810.

On the same website you’ll find an analysis of the executions carried out in England & Wales between 1800-1827. There were 2340 in all, an average of just under 84 per year. A significant number, to be sure, but far fewer than I would have guessed from reading Dickens. The article explains why:

It should be noted that only 20 or so crimes normally resulted in execution and that in the vast majority of cases (69-70%) the death sentence was commuted.

The huge number of capital crimes was inflated not only by endless acts of

Parliament mentioned earlier but also by the minute subdivision of capital

offences into individual categories. For instance there were seven

individual offences of arson that each carried the death penalty.

During that 28-year period only 380 people were executed for murder, which probably reflects the difficulty of identifying the assailant when the victim is unable to do so. Reliable statistics for the number of murders in England & Wales are only available from 1898 onwards (see this report in the House of Commons Library), but working backwards from the figure of around 300 per annum at the end of the 19th century, and allowing for the 250% increase in the population over the course of the century, gives a figure of around 85 per annum in 1800 (the number of executions for murder in that year was 12).

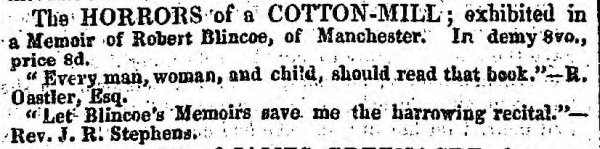

Last weekend the Guardian published an article about a foundling who was discovered in the St Pancras area of London in or around 1792, setting out the intriguing hypothesis that this child – who had been given the name Robert Blincoe – was the real-life inspiration for Charles Dickens’ fictional character Oliver Twist. It’s certainly plausible – Robert Blincoe published a memoir in 1828, nearly a decade before Oliver Twist was first serialised.

Advertisement published in The Odd Fellow; used by kind permission of Findmypast

The author Nicholas Blincoe, who is the great-great-great grandson of that foundling, has written a book titled Oliver Twist and Me. I haven’t read the book (it won’t be published in the UK until 4th September), but what I am intrigued to know is whether any of the descendants of Robert Blincoe have taken DNA tests in the hope of identifying the parents of the abandoned child?

It’s within reach of autosomal DNA, though it’s always difficult to knock down a ‘brick wall’ when you don’t have any names to go on – and it gets exponentially more difficult as the number of generations increases. However, in this instance there is also a small chance of discovering the father’s surname with a Y-DNA test, since we know that Nicholas Blincoe is a male line descendant. Whilst we might assume that mothers of foundlings were unmarried, this wasn’t always the case.

In the course of researching this article I came across another book, Unmarried Motherhood in the Metropolis: 1700-1850 by Dr Samantha Williams, a Cambridge University historian. I haven’t read this book either, and probably never will given the price (academic books are always expensive), but I fortuitously found a 35-page article by Dr Williams entitled The maintenance of bastard children in London, 1790-1834 which is free to download and crammed with interesting details and statistics.

Note: the article is in PDF format – whether it will open in your browser, in Adobe Reader, or go straight to your Downloads folder will depend on your settings.

Every adoptee’s story is different, but I know that some of you will see similarities in the tale of Corin Hirsch, who wrote about her own experience in the Guardian last weekend. You’ll find the article here – and, as with any Guardian article, you shouldn’t have to pay to access it.

My wife, Siân, has written an article that will resonate with many of you….

Gardens are all about enjoyment; part of this pleasure is watching the birds, bees, butterflies and other insects that are attracted by what we plant. However, over 15% of Britain’s population have asthma, over 50% of the population experience hayfever, and respiratory allergies are rising among children, young people and the elderly. Pets also experience plant allergies. Fortunately, we can easily avoid planting the worst culprits while continuing to nurture the wildlife.

Most pollen allergies are cause by wind-pollinated trees and plants; even rainy days can wash pollen closer to the ground, causing unexpected difficulties for some.

Tree pollen allergies occur between mid-March and early June; the most common and severe symptoms are caused by birch. Conifers, alder, yew, lime, plane, oak and hazel can also be problematic. Hayfever sufferers are allergic to grass pollen, at its peak from mid-May to end-July. Consider planting sterile or low-pollen varieties of ornamental grasses. Mow the lawn regularly before it sets seed; artificial grass will collect pollen if not regularly cleaned. Avoid strimming during hayfever season. Many ferns, weeds and plants in the aster family (such as chrysanthemums, dandelions and marigolds) are wind pollinated and can cause allergies.

Toxins in many plants and seeds - including day lilies, euphorbias, hellebores, peonies, foxgloves, chrysanthemum and oleander - can irritate skin and cause respiratory issues; always wear gloves whenever gardening or flower arranging. Minimise mould sensitivity by covering compost heaps and using low-allergen mulch. Wash hands well and launder gardening clothes separately.

The 80-90% of trees and plants pollinated by insects or birds tend to have brightly coloured, nectar rich flowers which are often scented; some have very little pollen. The Royal Horticultural Society, Allergy UK and The Royal College of Pathologists publish their recommendations for low allergen garden plants to help all of us create a healthier garden for everyone to enjoy.

As many of you will be well aware, after 14th October 2025 Microsoft will no longer be providing updates for Windows 10.

In the last issue I mentioned that Computeractive will be publishing a ‘Windows 10 Survival Guide’ in their 10th September issue, but I should also have highlighted the Microsoft climb-down in June, when they agreed to offer security updates for an additional 12 month period to home users (see this article from Forbes magazine). It was a pragmatic decision – in May 2025 over 40% of home users were still using Windows 10.

For many the Extended Security Updates (ESU) program will be free, and though you will have to jump through one or two hoops to qualify, doing so will make it very much easier to transfer to a new computer in due course. Naturally Microsoft are still hoping that users will buy new PCs, so you have to go right to the bottom of the page on their site which details the options in order to find out about ESU.

Even if you decide to buy a Windows 11 computer before next month’s deadline it’s still worth signing up for the ESU program for the old one, as it will mean you can safely go back to your ‘old’ PC if you find that you’ve forgotten to transfer some files.

Tip: when I was looking at the HP website this week I noticed that they were selling brand-new Windows 11 laptops for under £300 as part of their ‘Back to School’ promotion. For example, this model with 8gb of memory and 256gb of SSD storage is currently reduced to £279 from £449 – the Intel i3 processor would be too slow for gaming or photo-editing, but it will be fine for emails, web browsing, or genealogy. In fact, despite the low price, it’s probably faster than your current laptop PC.

Staying with Windows, I’ve just realised that last Sunday was the 30th anniversary of the official release of Windows 95. It might seem primitive now, but anyone who upgraded from Windows 3.1 will remember what a difference it made! As a developer I got early access to Windows 95, but in the event I never published any games that ran under Windows – it was such a big step for the programmers, most of whom were, understandably, much more interested in writing for games consoles.

I’ve mentioned before that I’m using an Excel spreadsheet to record events from my life – compensating for the fact that, like most people, I never really kept a diary. Many of the events are relatively minor, but I record them nonetheless in the hope that they’ll help me work out when other things happened: for example, I came across my ‘O’ and ‘A’ level exam papers which show the date and time of the exam. The next step is to dig out my old passports, so that I can record when I was out of the country.

However, it’s not just about dates and places, it’s also about people. Every now and again I think of someone from the past, but can’t necessarily remember their name. I’m not talking about close friends, they’re typically people I only met a few times, but where there is something about the person or the context that is memorable.

For example, in 1980 or 1981, not long after I ventured into home computer software publishing, I found myself talking to a customer who had been involved with computers for longer than anyone I’ve ever met – he had worked on Leo, the world’s first business computer. Leo was developed by J Lyons and Co to improve the efficiency of its chain of teashops: I’m sure that many readers will have visited a Lyons Corner House at some point in their lives!

45 years on I couldn’t remember his name, and I probably wouldn’t have remembered it 40 years ago, either. But, thanks to the Internet, I now know who he was, when he was born, when he died, and what his involvement in the project was.

It all began on Bank

Holiday Monday when I stumbled across a PDF copy of the newsletter of the Leo

Computers Society. Up to that point I hadn’t considered the possibility

that there was a society for a computer that was conceived in 1947 – but thinking

about it now, I probably should have done. Half-hidden on the society website

was another PDF – a comprehensive list of books about Leo, listing their

authors and giving brief details of the content.

It all began on Bank

Holiday Monday when I stumbled across a PDF copy of the newsletter of the Leo

Computers Society. Up to that point I hadn’t considered the possibility

that there was a society for a computer that was conceived in 1947 – but thinking

about it now, I probably should have done. Half-hidden on the society website

was another PDF – a comprehensive list of books about Leo, listing their

authors and giving brief details of the content.

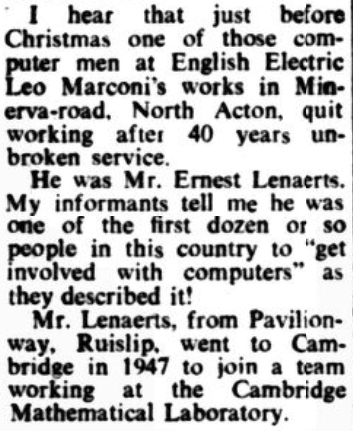

Acton Gazette of 5th January 1967

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

Used by kind permission of Findmypast

On page 8 I finally spotted a name that I recognised – it was one of those names you could never forget. Except that I had. My mysterious customer was Mr E H Lenaerts, a pioneer of computing.

In October 1948 Ernest Lenaerts set down a handwritten description of the EDSAC computer which was being built at the University of Cambridge, and is (according to the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park) regarded as the first practical general purpose stored program electronic computer. In his 1985 memoir, Maurice Wilkes – the designer and co-creator of EDSAC – recounted how Lyons provided funding of £3000 and agreed to provide an assistant to work on EDSAC. Ernest Lenaerts was initially seconded from Lyons to Cambridge for a year, but according to Wilkes he stayed longer.

One the reasons that my encounter with Ernest Lenaerts stuck in my mind resulted from a comment he made when we first met: “I used to do programming”, he told me, “but in those days I did it with a soldering iron”.

I’m not sure if it was on that first visit to our office, or a subsequent one, but we got talking about the KIM-1 microcomputer I owned, and I bemoaned the fact that it was not working. “I’ll get it working”, he said, and the next time he came in it was working perfectly! I just wish I still had it, as a reminder of my encounter with a pioneer of computing.

Note: on the website of the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge you’ll find this page dedicated to Ernest Lenaerts. I’ve never visited the museum, but I think it would make an interesting outing for my 75th birthday, which is coming up very soon!

How are you recording your own memories for posterity? Do you write things down, or is that something you’re planning to do ‘one day’?

So far this year my wife and I have benefited from £85 of credits on our electricity bill, thanks to EDF’s Sunday Saver scheme: all we had to do was reduce our peak-time usage (4pm-7pm Monday to Friday) as a percentage of our total usage, which wasn’t difficult. When we succeeded we got between 4 hours and 16 hours of free electricity the following Sunday, and in the one week when we didn’t there was no penalty – we couldn’t lose.

If that’s not enough to tempt you to switch supplier, how about a £75 bill credit when you sign up with EDF by 9th September using this link? After that date the link will still work, but the incentive comes down to £50 – which is still a useful sum. If you switch using that ink we’ll also get a bill credit so “thank you” in advance.

By the way, EDF sell gas as well as electricity, but there is no mains gas where we live so we’re only signed up for electricity. We’re not mad keen about using heating oil, but it’s not feasible to switch to a heat pump in such a higgledy-piggledy old building. In any case, we now only use about a third of the oil we used 25 years ago, so we feel we are doing our bit – getting rid of the AGA we inherited when we moved in made a big difference, as did upgrading to a smaller but much more efficient boiler.

Finally, the list of Tracing Your Ancestors…. books available in Kindle format for 99p (in the UK) has lengthened since I last wrote – as I write (late on Thursday evening) there are 10 titles in the series reduced to 99p. Please follow this link for the latest list.

As hoped the Findmypast offer HAS been extended - until 15th September. Please continue to use the links in the main article - I will be sending out a newsletter shortly with more information.

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2025 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links – if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins (though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser, and any browser extensions that are installed). Proud to be an Amazon Associate.