Newsletter - 10th July 2019

ThruLines goes live at Ancestry

Mary Berry is NOT my ancestor - but my 'brick wall' came tumbling

down

Discover your ancestors in film archives

Finding Masterclasses (and other articles)

How autosomal DNA is inherited

What does it mean to be genetically Jewish?

Growing up in London: a new series

How espionage and ambition built the first factory

Review: Women's Suffrage in Scotland

The most successful author you've never heard of?

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published

2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue (dated 28th June)

click here;

to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between this

paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009,

so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main LostCousins website click the

logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join -

it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition

of this newsletter available!

ThruLines goes live at

Ancestry

On 1st July ThruLines permanently replaced DNA Circles, having been

optional while it was in beta test. Although it's a feature that's only

available to those who tested their DNA with Ancestry, it's important to

realise that ThruLines suggestions for 'potential ancestors'

are based on family trees - Ancestry aren't using DNA to prove the connection.

In other words

they're hints - some will be more useful than others, but even when the hint is

wrong good things can come out of it, as the next article demonstrates.

Mary Berry

is NOT my ancestor - but my 'brick wall' came tumbling down

When I looked at ThruLines last

Wednesday morning I noticed that there two potential ancestors I hadn't seen before:

Stephen Berry and his wife Mary.

When I looked at ThruLines last

Wednesday morning I noticed that there two potential ancestors I hadn't seen before:

Stephen Berry and his wife Mary.

I was particularly intrigued

because the surname Berry hadn't come up at all during my researches, and

whilst this could mean it was a 'red herring', I've learned over the years that

clues can come from the most surprising sources.

When I took a look at the

tree on which this suggestion was based I realised that the tree owner had

inadvertently combined two families into one - yes, the daughter Mary had

married an Edward Smith, which fitted, but my great-great-great grandmother's

maiden name was Rowse, not Berry. Smith is a very

common surname, and all this took place in London, which at the time was the most

populous city in the Western world, so it was understandable that a mistake

might have been made.

Nevertheless, rather than

dismissing the information out of hand I decided to make sure that I hadn't missed

any children, by checking for Smith births with mother's maiden name Rowse in the GRO birth index. When the GRO's indexes went

online a couple of years ago I used them primarily to help knock down 'brick

walls', or to find missing children revealed by the 1911 'fertility census' - I

didnít methodically go through every family in my tree, mainly because I was

hoping the GRO would update their search to make it less 'clunky' (which sadly hasnít

happened yet).

Fortunately Findmypast

took up the baton that the GRO dropped - most entries in their birth index now

include the mother's maiden name, even for the period from 1837-1911 when it

wasn't shown in the original GRO quarterly indexes. Note that you donít need a

subscription to search at Findmypast - it's only when you try to look at the

record that the drawbridge goes up, and often the search results will tell you

all you need to know (use this link

to check it out yourself - note that you might have to log-in).

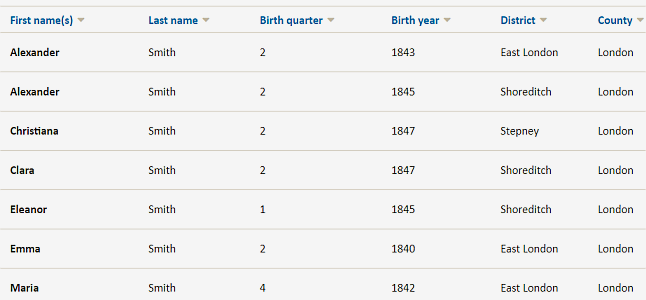

These are the results I got

when I searched for births between 1837-1847:

Clara, Eleanor, Emma, and

Maria are all in my tree, but the two Alexanders and Christiana aren't. Even

though the births are in the same part of London I could tell from the dates

that they must have a different mother, so I wondered whether it might be a

case of two brothers marrying two sisters. This would be very good news, because

Mary Ann Rowse had been a 'brick wall' for about 15 years,

and any clue would be worth having.

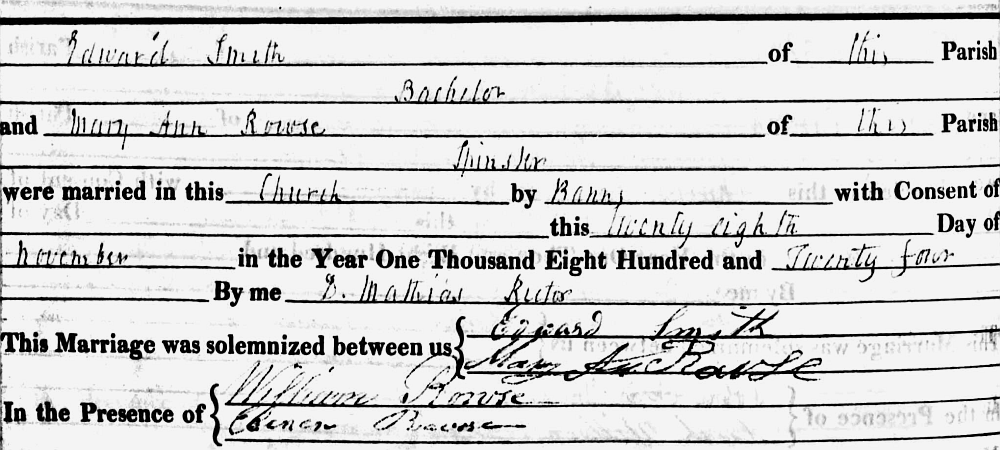

Before continuing I'm going

to tell you what I knew about Mary Ann: when she married Edward Smith in 1824

at St Mary, Whitechapel the witnesses were William Rowse,

and another Rowse whose name began with E - my best

guess was Ebenezer, but the writing was so bad it really was just a guess.

Because it was 13 years before civil registration was introduced in England

& Wales there was no indication of her father's name - he might have been

one of the witnesses, but then again, he might not.

The 1851 Census showed her age

as 43, and her birthplace as Soho, Middlesex; when she died in 1855 she was

just 47 years old, tallying with the age shown in the census, and implying that

she was born in 1807 or 1808 (making her a young bride when she married in 1824

- she would have needed the permission of her parent or guardian). Soho is in

Westminster, so when Findmypast added the Westminster

parish registers a few years back I had a good look for Mary Ann - and found

a Mary Ann who was baptised to John & Mary Rouse at St Margaret's Westminster.

Not the right parish or the same spelling of the surname, and no sign of a

William or Ebenezer, but it was certainly worth including a note in my tree -

just in case some other corroborating evidence came to light.

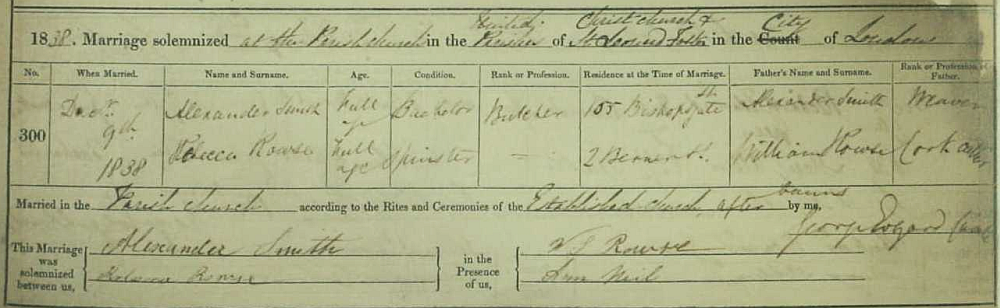

Anyway, back to last Wednesday

morning - my first objective was to find the marriage of the other Smith & Rowse couple, and hope that it was

after July 1837 (which seemed quite likely as there were apparently no children

born before 1843). In the event I found it in 1838:

© Reproduced by kind

permission of the London Metropolitan Archives and Ancestry

There two key pieces of

information that stood out: the bride's father's name was William Rowse, which tied in neatly with first witness to the

marriage of Edward Smith and Mary Ann Rowse; secondly,

the bride's name was Rebecca, which happened to be the name of my

great-great-great grandmother (daughter of Edward & Mary Ann).

At this point I was quite

encouraged - the only fly in the ointment was the possibility that the William Rowse named as the bride's father was also the W S Rowse who had signed as a witness, because the signature

looked nothing the one from the 1824 marriage of my great-great-great

grandparents (see below):

© Reproduced by kind

permission of the London Metropolitan Archives and Ancestry

At Findmypast I'd found a Mary

Ann baptised to a William and Rebecca Ann Rowse in

Stepney in 1811, but with a birth year of 1808 recorded - otherwise she'd have

been very unlikely to marry in 1824! There was no image - it was a transcript

sourced from FamilySearch. Perhaps this was the right family at last - but if

so, was the Soho birthplace simply wrong? And why hadn't I found this baptism

in the London Metropolitan Archives collection?

Now that I was increasingly

confident that my Mary Ann was the daughter of William & Rebecca I decided

to go back to the London

Metropolitan Archives collection at Ancestry for another look. I found the

baptism of Rebecca at St Mary, Whitechapel in 1814, which fitted in with an 1838

marriage - and eventually spotted the baptism I'd been looking for all these

years. My ancestor was recorded as 'Many Ann Rowse'!

But I wanted more proof. Who

was W S Rowse, the witness at Rebecca's wedding; who

was Ebenezer (??) Rowse, the second witness to Mary

Ann's marriage? Was I in danger of making the same mistake as the Ancestry tree-owner

who had set me off on this quest, by merging two separate families into one?

I realised that the the best

way to prove the connection was to find signatures that matched, so I resolved

to find as many marriages as possible. The first step was to identify all the

children of William and Rebecca Ann - there were 6 in all, 5 of them daughters

(no wonder William was happy for Mary Ann to marry at such a young age!). And as

they all married, including the son - William Samuel - who was clearly the W S Rowse who witnessed the marriage of Alexander Smith to

Rebecca Rowse, I had plenty of evidence to confirm my

findings.

Ebenezer, by the way, was actually Eleanor; Alexander Smith isn't, so far as I can

tell, related to Edward Smith; and Mary Berry certainly isnít my ancestor.

Nevertheless, thanks to the muddled tree that ThruLines

discovered, I was inspired to knock down a 'brick wall' that had blocked my way

for 15 years - and all in a morning!

The moral of the tale is that

whilst luck certainly plays a part, it's up to us to grab hold of the

opportunities that come our way and make the most of them. This is far from the

first time that the names and signatures of marriage witnesses have provided me

with vital clues, and you wonít be surprised to learn that one of the other

occasions also involved my Smith ancestors.

I quite often get emails from

people who tell me that this or that surname is so common that they've given up

all hope of finding the answer. But itís not usually the magnitude of the problem

that stops us succeeding, it's a lack of determination to find the answer - sometimes

people are so convinced that they're going to fail that they don't order the

certificates or buy the subscriptions that could provide the solution. Watching

the tennis on TV last week it wasn't difficult to tell which players had the right mentality to be winners, and which were

setting themselves up for failure. Whilst most of you are amateur genealogists,

like me, that doesnít mean that we have to fail - I

can remember when everyone playing at Wimbledon or competing in the

Olympics was an amateur!

Postscript: Finding Mary Ann's

parents was just the start - every time we knock down one 'brick wall' there

are at least two more behind it! Put it another way, the more experienced and

successful you are, the more 'brick walls; you'll have - which is why

connecting with cousins, no matter how distant, is crucial to your continued success.

In the mid-19th century graveyards

in many British cities were full, prompting the development of new out-of-town

cemeteries. Now, it seems, we're running out of space again - prompting one

expert to propose burying our loved ones alongside motorways. See this Guardian

article

for more details and some of the other ideas that are being suggested. But

perhaps you have a better suggestion? If so, please let me know.

In Australia construction

works on the Sydney Metro uncovered the remains of a 19th century cemetery - you

can read about it here.

Discover

your ancestors in film archives

Over the past decade I've

written about a number of major film archives, most of them offering free

online viewing, and as there's an article on this topic in the latest issue of Who

Do You Think You Are? magazine I thought this would be a good time to

provide an update.

I first wrote about the East Anglian Film Archive in 2012 - there

are around 200 hours of footage online, all of it free to view, but this is

only a very small fraction of the material in the collection. The earliest

footage dates from 1896!

British Pathť

is another site I've mentioned many times - and whenever I do, there's always

someone who spots an ancestor in one of their newsreels!

I watched the BBC documentaries

about the films of Mitchell and Kenyon (there are some short clips from their

work here,

but you'll need to register). I recorded the programmes when they first aired, over

a decade ago, but you can pick up second-hand DVDs of the series at very low

prices here.

The British Film Institute

National Archive has an immense collection of films or all types - and whilst

most are only available on subscription there's still a lot that is free (follow

this link).

A site I hadn't discovered

before reading Jonathan Scott's article in Who Do You Think You Are? is

London's Screen Archives, which hosts nearly 80 collections held by the London

Metropolitan Archives, London Transport Museum and many others - you can find

out what's available here.

When I searched for Ilford, the town where I grew up, I found a wealth of

material held by Redbridge Museum and Heritage Centre, all of it free to view,

and mostly home movies.

Tip: on this site you can

add music to silent movies - it's amazing what a difference it makes.

Another site new to me was

the Media Archive for Central England - you'll find it here but I had trouble with the search

so wasn't able to check it out properly in the time available. See the magazine

for other film archives around the country.

Finding

Masterclasses (and other articles)

My DNA Masterclass, which provides

the optimal strategies for anyone who has tested with Ancestry DNA (but will

also help those who have taken an autosomal test with another provider) is

frequently mentioned in the newsletter. But where can you find it?

The good news is that there

are links to all of my Masterclasses, covering a wide

range of topics, from the Subscribers Only page at the LostCousins site.

However you donít need to be a subscriber to make use

of the Masterclasses - every newsletter has a search box at the top that allows

you to search every LostCousins newsletter published in the last 10 years

(since February 2009, to be precise).

The results look like a

standard Google search, but - apart from the usual adverts at the top - the

results are all from the newsletters. This means it's really

easy to find articles from past newsletters - far easier than it would

be if there was an index.

For example, if you wanted to

find the DNA Masterclass you would search for 'dna

masterclass'. To find all of the Masterclasses search for 'masterclass'; to

find other articles just type in one or two key words, such as 'bigamy', 'GRO',

or 'illegitimate births'. There's no need to restrict

yourself to topics you remember reading in the newsletter - even I can't

remember everything I've written about!

How autosomal

DNA is inherited

If you'd like to have a

better understanding of how DNA is inherited, all you need is a deck of playing

cards - we're going to use it to represent your parents' DNA.

Here's what to do: first remove

the Aces - you're not going to need them - then separate the remaining cards

into two piles, one with the minor suits (clubs and diamonds) and the other with

the majors (hearts and spades). Now turn them over so that you can't see them

and thoroughly shuffle each pile, keeping them separate.

When youíre satisfied that

they're randomly shuffled deal 12 cards from each pile face down; now take the

24 cards you've just dealt and, keeping them face down, shuffle them again.

Finally turn the cards over and fan them out so that you can see the suit of

each card.

How does this relate to DNA?

Well, the clubs and diamonds represent the DNA you inherited from your paternal

grandparents, hearts and spades the DNA from your maternal grandparents; the

red cards represent the females, and the black cards the

males.

In the nest photo I've sorted

the cards into suits. When you do this you'll notice

that you have the same number of cards from each couple (ie

12), but the chances are that you didn't inherit precisely 6 from each

grandparent. This demonstrates that whilst we get 50% of our DNA from each of our

parents, and they got 50% of their DNA from each of their parents (and so on), we

donít inherit precisely 25% from each grandparent.

If you were to start again

and select another 24 cards following the instructions above

you'd find that about half of them match the first set, which demonstrates that,

on average, full siblings share 50% of their DNA. But don't do it just now, because

there's another part of the exercise that you'll need to do first.

Although in this simulation

you can identify the DNA that came from each grandparent, you wouldnít be able

to do this in real life - at least, not without some help from your cousins. Segments

of DNA that you share with one of more maternal cousins must have come from

your maternal grandparents, whilst segments that you share with one or more paternal

cousins must have come from your paternal grandparents (of course, if your

parents were related it's a little more complicated).

Most of the time we donít need

to know which segments of our DNA came from which ancestor - what we really want

to know is how we are related to the genetic cousins we've been matched with. And

to do this you need the help of documented cousins who have also tested, ideally

with the same provider. After all, if you and your cousin Jack both have Rosemary

on your list of matches, the chances are that Rosemary is connected to you

through one of the ancestral lines that you share with Jack.

Of course, just because you

and a cousin have common ancestors doesnít mean that you'll share a detectable

amount of DNA - it mostly depends how closely related you are. In the playing

card example above we looked at inheritance over a single generation - the 48

card deck that we started with represented the DNA of your two parents, whilst the

24 cards you ended with represented your DNA. Halve the number of cards again,

and now those 12 cards represent the DNA that you pass to one of your own children

(of course, they'll receive a similar amount from their other parent):

The second set of 12 cards

are the result of going through the whole process a second time: they represent

the child of your sibling. - in other words the two of

them are 1st cousins.

Note that there are just 3

cards that appear in both selections. 3 out of 24 is one-eighth or 12.5%, which

happens to be the average amount of DNA shared by 1st cousins (as you will see

if you go through the process multiple times).

†

Let's just recap what we've

learned: full siblings share 50% of their DNA on average, even though they have

identical ancestors; 1st cousins share just 12.5% of their DNA, even though

they share half of their ancestors. It doesnít seem right, does it? But it is -

and the reason for the discrepancy is that only half of DNA gets passed on from

one generation to the next.

In fact, with every

generation the amount of DNA we share with our cousins reduces by three-quarters

- thus 2nd cousins share, on average, just 3.125% of their DNA and 3rd cousins

a mere 0.781%. It's just as well we have more autosomal DNA than there are

cards in a deck (around 3 billion base pairs).

In practice all 2nd cousins and

almost all 3rd cousins share a detectable amount of DNA, though the chances of

a match reduce significantly after that - by the time you get to 6th cousins

there's only an 11% chance, and for 8th cousins it's just under 1%. On the

other hand, we have so many distant cousins that they'll account for over 99%

of all our matches! DNA is full of contradictions - itís no wonder that so many

people are confused by it.

There's a table in my DNA

Masterclass which shows not only the average amount of DNA shared with cousins

of different degree, what the chances are that two cousins will share DNA, and how

many cousins we have at each level, but also how many cousins you would expect to

find if they all tested with Ancestry. Of course, that's unlikely to happen,

but so many tests have been sold that the proportion of our cousins who have already

tested could well be 5% or more.

What does it

mean to be genetically Jewish?

Although ethnicity estimates

aren't normally of any practical value, one thing they're good at picking up is

Jewish ancestry. Sometimes this is an unexpected discovery - and a common question

that people ask is "Does this mean I'm Jewish?".

I have ancestors from Germany

and Wallonia, but I still think of myself as English. On the other hand, I get

the impression that anyone in the USA who has an Irish ancestor thinks of

themselves as Irish - at least when it comes to celebrating St Patrick's Day!

A thought-provoking article

in the Guardian last month examined the relationship between Jewish

ancestry and Jewish identity - it's well worth reading.

Growing up

in London: a new series

Over the past 6 months I've

been indulging in a guilty pleasure - dipping into the pages of Growing Up

In London 1930-1960, a wonderful book which was compiled and edited by

LostCousins member Peter Cox, who interviewed more than one hundred U3A members

aged between 75 and 95 (the interviews were conducted in 2014, so they would

have been born between the wars).

On every page there are quotes

that remind me of my own childhood, or of the stories I heard from my parents -

and whilst all the memories are from Londoners, the vast majority will be just

as relevant to those who grew up in different parts of Britain.

Normally I'd simply read a

book and review it, but there are some books which deserve to be consumed in

small portions, and savoured: Growing Up In London

is one of them. So with the permission of the author

I'm going to be featuring short excerpts from the book over the coming months -

each just a paragraph or two, but every one evoking the spirit of a bygone age

(albeit a time that is still within living memory).

The first excerpts come from

p.31, where the memories are of bathrooms - or the lack of them. These two comments

reminded me of my own childhood - how things have changed!

"Toothpaste

is something we take for granted nowadays. What we used then was a powder

called Eucryl that felt as if we were brushing our teeth

with chalk and sand."

"Our

hair was washed over the sink in the scullery using ordinary soap. You had to

check that all the soap came out."

I can't remember the brand of

the toothpowder I used as a child, but it came in a small flat round tin. It was

a lot more economical than modern toothpastes, since you had to work hard to get

any on your toothbrush - and for this reason it was probably safer for children.

When I graduated from washing

my hair with soap it wasn't to shampoo, but washing-up liquid. That couldnít have

happened previously because we didnít have washing-up liquid in the 1950s - at

least, not in our house (we used Daz washing powder to

clean the dishes, which seems rather strange now).

L P Hartley wrote at the

start of his most famous book, The Go-Between, "The past is a

foreign country: they do things differently there" - and we certainly did,

didnít we!

There are thousands of reminiscences

in the book - it's a goldmine. Growing Up In London was published in

hardback at £20, and even the cheapest used copy on Amazon cost £35 when I

checked - but you can purchase it direct from the author for just £10 plus

postage if you follow this link to his

website and mention that you are a LostCousins member (Peter Cox will also sign

and dedicate the book on request). If youíre outside the UK and ordering a copy

as a gift place your order well in advance so that the book can be sent by

surface mail, which is a lot cheaper (especially if you are buying more than

one copy).

How

espionage and ambition built the first factory

Almost a

decade ago I read a fascinating book about the Industrial Revolution (you'll

find my brief review here)

but this BBC article

has an intriguing story that I donít remember from the book.

Thankfully I've never had to

work in a factory, although I'm sure most modern British factories are a long

way removed from the 'dark satanic mills' that William Blake wrote about in the

early 19th century.

Although fossil fuels have

been in the ground for millions of years, it was only in the mid-19th century

that the advantages of crude oil were recognised. So how were the wheels of

industry oiled before then?

I found an article from the MRS

Bulletin which has all the answers - you'll find it here

(it's in PDF format).

If you look through your

family tree you'll probably notice that until the second

half of the 19th century your ancestors tended to be named after other family

members - usually parents, grandparents, uncles or aunts. Some may be named for

godparents, but most parish registers don't record who the godparents were (Catholic

registers are the main exception).

Then parents started to be more

creative - this may have been forced upon them by the reduction in infant mortality,

which meant that many families had 10 or more children who survived, but I

suspect that many were also influenced by what they read, and later by the films

that they saw.

Fashions come and go, so you

can often tell how old somebody is just by knowing their name. A recent BBC

article draws on an analysis of baby names in England & Wales from 1996-2017

- you'll find it here.

†

Probate genealogist (or heir-hunter) Anna Ames is one

of my favourite literary characters, so when her creator, the author Geraldine

Wall, sent me a draft of her latest novel a couple of months ago I was absolutely

delighted.

Probate genealogist (or heir-hunter) Anna Ames is one

of my favourite literary characters, so when her creator, the author Geraldine

Wall, sent me a draft of her latest novel a couple of months ago I was absolutely

delighted.

What I love about the series is

the interaction between Anna's work and her personal life. I've watched her

children grow up and her daughter leave home, I've sympathised as she cared for

her husband (who had early onset dementia), I've shuddered as things have gone

wrong, and cheered when they've gone right.

In the early books of the

series she found her mother, but couldnít bring

herself to like or understand her during the brief period they were together. In

this latest book she finds herself researching into her mother's background, and searching for her maternal cousins: the

discoveries she makes help Anna to appreciate the pressures her mother was

under, and comprehend why it was she abandoned her young daughter.

All this is against the

background of her day job - it's just like real life, in other words!

Will this be the last book in

the series? I hope not - I'd hate to think that I would never meet these

wonderful characters again. Currently it's only available in Kindle format, but

previous instalments also came out in paperback format, so I suspect this one

will too.

If, like me, you've been

following Anna Ames you won't need my encouragement to buy this book. If you

haven't, I recommend you start with the first book in the series and read them

in sequence - believe me, once you've read the first one you won't want to stop!

The links below will take you

a page that lists all of the books in the series - the

first is File Under Family. Using the appropriate link will enable you

to support LostCousins - even if you end up buying something completely different.

(Unfortunately Amazon don't allow you to support

LostCousins when you buy from their Australian site - it doesnít have an affiliate

scheme at the current time.)

Amazon.co.uk††††††††††††††††††† Amazon.com†††††††††† ††††††††† Amazon.ca

Review:

Women's Suffrage in Scotland

Rather than writing a history of women's suffrage from

a Scottish perspective, Carole O'Connor has taken a refreshingly different

approach. The author devotes a chapter to each of the major cities and regions

of Scotland: she begins with a short history and description from a range of

perspectives (work, education etc), then follows up with pen pictures of the

key figures who played a part in women's suffrage.

Rather than writing a history of women's suffrage from

a Scottish perspective, Carole O'Connor has taken a refreshingly different

approach. The author devotes a chapter to each of the major cities and regions

of Scotland: she begins with a short history and description from a range of

perspectives (work, education etc), then follows up with pen pictures of the

key figures who played a part in women's suffrage.

Some of the people she writes

about were anti-suffrage, such as the Marchioness of Tullibardine

(later Duchess of Atholl), who despite her views

became the first woman in Scotland to be elected to Parliament. (She also had a

steam engine named after her.)

The book also features women

who, though not actively involved in the suffrage movement, nevertheless contributed

to its progress - and some men who supported the cause, including Keir Hardie.

You donít need to have a keen

interest in women's suffrage in order to benefit from this book - I suspect

that many researchers with Scottish ancestry will find it useful. It's

available now in the UK, either as a paperback or in Kindle format, but wonít be

released in North America until the fall. The published price is £12.99, but when

I checked there were new copies available through Amazon Marketplace for under

£10 (including postage), and the Kindle version is under £5.

Amazon.co.uk††††††††††††††††††† Amazon.com†††††††††† ††††††††† Amazon.ca

The most successful

author you've never heard of?

You've almost certainly seen

books by David Gerald Hessayon - in fact you probably

own at least one of them. And yet few people would recognise the name of this author

whose books have sold over 50 million copies (and no, he doesnít use a nom

de plume).

Give up? Here's a link to his most famous book......

This is where any

major updates and corrections will be highlighted - if you think you've spotted

an error first reload the newsletter (press Ctrl-F5) then check again before writing to me, in case someone else has

beaten you to it......

Peter Calver

Founder,

LostCousins

© Copyright 2019

Peter Calver

†

Please do NOT copy or

republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only

granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However,

you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for

permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins

instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?