Inside the 1939 Register

Updated 1st November 2024

Free access

to the 1939 Register at Findmypast ENDS MONDAY

What was the 1939 Register?

How the

register differs from other censuses

Why some

names are crossed out & other mysteries

Why are there

more transcription errors than usual?

How to search

the 1939 Register

Pitfalls to avoid

when searching by address

Closed records

are NOT indexed

How to work

out who the hidden people were

Who should we

be looking for, and why?

Why do some

people have two entries

Insights we can get from identity cards

How the

numbers from identity cards were used

Tracking down evacuees using

LostCousins

How evacuation was planned in

1939

Qualifications desirable in an

enumerator

This is a Special Edition of the

LostCousins newsletter; for other issues please visit the LostCousins website and click the

'Latest Newsletter' link in the menu.

Free access to the 1939 Register

at Findmypast ENDS

MONDAY

Until 11.59pm GMT on Monday 4th November you can access the

1939 National Register for England & Wales free at Findmypast (make sure you

download the records you find to your own computer before the offer ends!).

The 1939 Register wasn’t a census, but for England

& Wales it’s the closest thing to a census that has survived between 1921

and 1951, since there was no census in 1941 thanks to the war, and the 1931

Census was destroyed during World War 2 – not by enemy action, but by the

carelessness of the soldiers who were supposed to be guarding it.

However there are some important differences between the 1939

Register and the decennial censuses from 1841-1921, so this newsletter is devoted

to an inside look at the 1939 Register.

Search the 1939 Register at Findmypast.co.uk

Search the 1939 Register at Findmypast.com.au

Search the 1939 Register at Findmypast.com.ie

Search the 1939 Register at Findmypast.com

Sylvanus Percival Vivian, Registrar General for

England &Wales between 1921-45, was the driving force behind the creating

of the 1939 National Register. Having organised the 1921 and 1931 Censuses, and

having written critically about the 1915 National Register, he recognised that

infrastructure for the 1941 Census could be used to create a National Register,

should war break out. His preparations for the 1941 census were, therefore,

intertwined with the planning of a national registration system for the

purposes of conscription, which began at least as early as 1935.

However the National Register wasn't created simply as a

means of identifying fit young men who could be sent abroad to die for their

country: the Great War had demonstrated how important it was to effectively marshall resources on the Home Front. It was also used as

the basis for the issue of ration books – which is possibly why some people

managed to be recorded more than once – and when identity cards were abolished the

registers continue to be used by the National Health Service, as a way of keeping

track of patients as they moved from one area to another.

How the register differs from other censuses

We're used to censuses that aspire to record everyone

in the land - but that wasn't what happened in 1939, even though it was

organised in a similar way.

A key task of the enumerators who collected the data

was to issue identity cards - and for this reason military personnel and

government workers who already had ID cards are unlikely to be recorded in

the Register. According to the National Archives (TNA) research

guide:

The Register was not meant

to record members of the armed forces and the records

do not feature:

- British Army barracks

- Royal Navy stations

- Royal Air Force

stations

- members of the armed

forces billeted in homes, including their own homes

However, the records do include:

- members of the armed

forces on leave

- civilians on military

bases

Note: it's

rare to find a member of the armed forces on leave in the Register, but you'll

find an example in one of the articles below.

Other key differences compared to the censuses are

that relationships are not shown, middle names are rarely shown in full, and

places of birth are not listed. However, precise dates of birth are given, and

this information might well save us the cost of buying a birth certificate,

especially for our more distant relatives.

Tip:

birthdates are not always recorded correctly - I have two great-aunts

who were twins, but if you relied on what the enumerators wrote down (they were

different enumerators because both of the sisters had

married before 1939) you would think they had been born a month apart. I've no

idea whether the mistake was made by the husband or the enumerator - but it

certainly wasn't the transcriber.

Why some names are crossed out & other mysteries

The 1939 Register was a working document – unlike

censuses, which were checked, analysed, and then archived, the National

Register was updated as changes occurred. For example, if a woman married she would normally adopt her husband's surname - and

if this occurred after 29th September 1939 a new identity card had to be

issued.

Tip: the use

of identity cards didn't end when the war was over - they continued in use

until 1952.

When the National Health Service was founded in 1948

the National Register was used as the basis of the NHS Central Register, and in

some parts of the country this continued into the early 1990s. As a result many name changes were recorded as the result of

marriages (and divorces) that took place in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. There

may even be some later changes - but I haven't seen any yet.

Here's an example of a name change on marriage:

![]()

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of

The National Archives, London, England and Findmypast

This tells us that May E Lawson became Dalrymple on

her first marriage (which was in 1951), and Noon on her second marriage in

1955. She died in 1985, but the record would be open in any case as she was

born in 1904, which is more than 100 years ago.

Changes weren't made immediately - there was

usually a delay - and in the example above you can see the change of name to

Dalrymple seems not to have been recorded until early 1955, by which time Mrs

Dalrymple (nee Lawson) was well on her way to marrying again - she married

Frederick E Noon in the third quarter of that year.

This means that where a date is shown all you can

conclude is that the event must have happened prior to that date. You are NOT

seeing the date on which the person married or divorced.

Tip: information in

the same colour ink and handwriting is likely to have been entered at the same

time - without this clue I might have associated the 1955 date with the second

marriage.

If there is a change of surname recorded

you can usually search using either surname. Unusually May E Noon has only been indexed under her final surname, possibly

because it's really hard to read her original surname (Lawson). But you're more

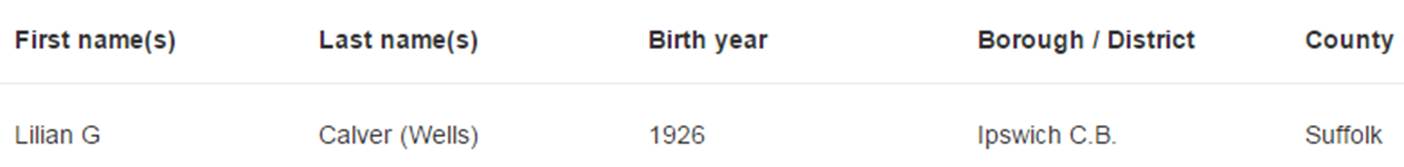

likely to see a search result that looks like this one:

That's my mum! Note that the original surname - the

maiden surname in this case - is shown in parentheses. By the

way, her family didn't live in Suffolk - but my mother's school was

evacuated from Ilford in Essex to Ipswich. I'd probably never have known about

this had it not been for the 1939 Register.

Why are

there more transcription errors than usual?

If you're used to just typing in names and seeing

results pop-up you might be frustrated by the number of transcription errors. Fortunately it's unlikely that they'll prevent you finding

the right records because there are so many different ways of searching - and

anyway, most transcription errors can be overcome by the judicious use of

wildcards. But it's important to understand just why there are more errors than usual.

First of all, there was a war on – the enumerators don't seem to have been

as careful with their handwriting as one would have liked. The fact that they

were using fountain pens probably didn't help – there tends to be too much ink,

so that some of the details disappears into a blob. And the transcribers also

had to decipher entries that had been crossed through.

However, the biggest challenge for the transcribers

was the result of privacy concerns - these records were not due to be opened

until 2040, by which time everyone recorded would have been over 100 years old.

This is why we could initially only see records for people who were born over

100 years ago, or whose death had been recorded in the register (some other

records have since been opened up for people who are

known to have died).

This meant that the transcribers weren't given an

entire page to work with - instead the page was divided into columns of data,

and these were given to different transcribers, none of whom could see the entire

entry for any individual, making it much more difficult for them to interpret the

handwriting. This ingenious process also generated errors even when the

transcribers got it right - on some pages the columns of the transcription were

'out of sync' when the page was reassembled, so that part of one record was

combined with part of the next record. Such errors look ludicrous to us, seeing

complete entries, but the transcribers of that page might not have done

anything wrong.

I'm never one to criticise transcribers because

it's not a job I would want to do, even though I'd probably be quite good at it

– but in this instance the challenges were greater than usual, and we have to remember that what we see isn't what they

saw. Because in most cases the enumerator only wrote down the last two digits

of the birth year it was relatively easy for years to migrate from one century

to another.

For example, I saw an entry for a schoolgirl whose birth

year had been indexed as 1883 - this was obviously incorrect when you saw the

entire record, but viewing the birth year in isolation I would have made

precisely the same mistake (and I suspect you would too). Only if I had known

that the individual concerned was still at school might I have deduced that the

enumerator intended the entry to be read as '33', not '83'. (Many thanks to

that schoolgirl, now a LostCousins member, for allowing me to see her record

before it was closed.)

Note: when you are able

to consult the original record the transcription acts only as a finding guide;

this means that errors in a transcribed record, no matter how ridiculous they

seem, are generally of relatively little consequence.

How to

search the 1939 Register

There are two ways to search – you can search by name,

or you can search for an Address. But most of the time you'll want to search

for a person, because you can include location information in a person search

if you want:

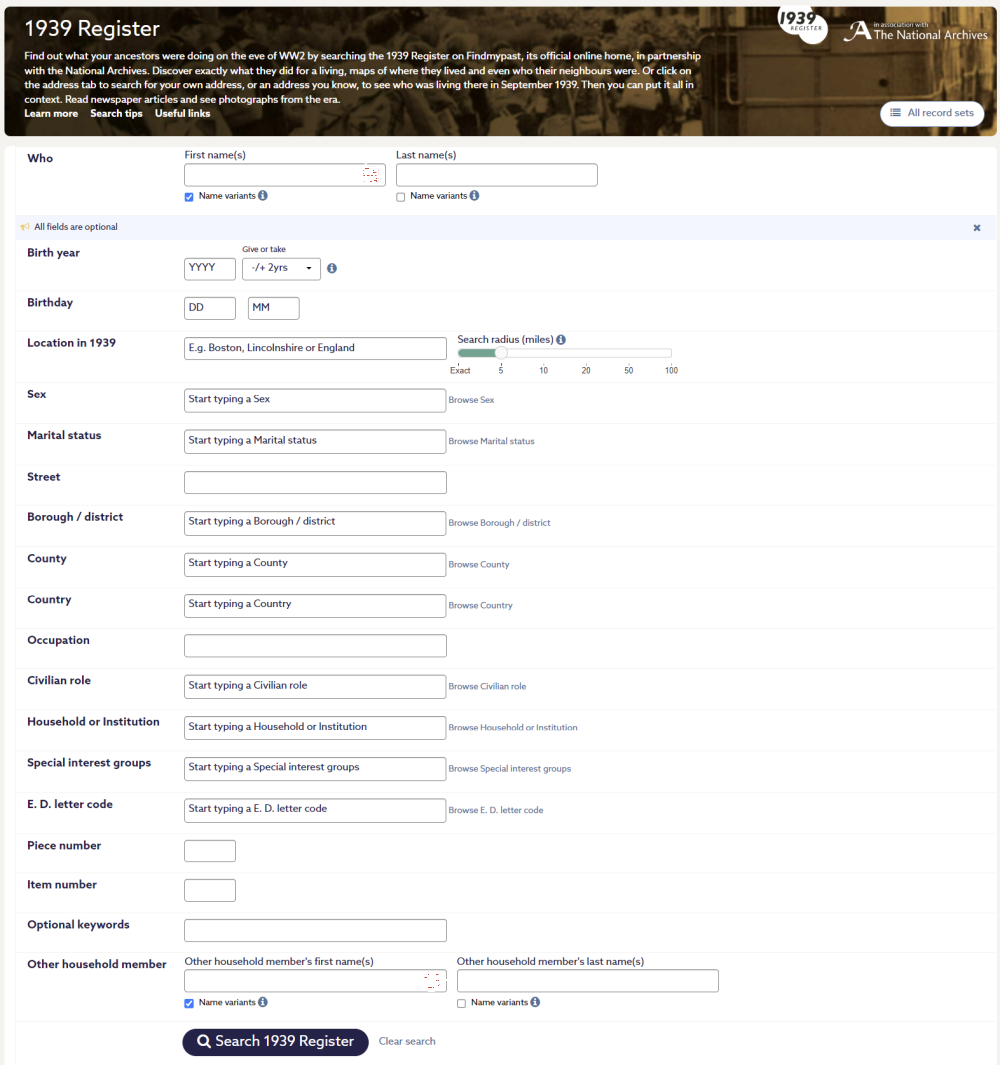

As you can see, the 1939 Register search form looks

quite similar to the page we see when we search the

1911 Census at Findmypast, but with the addition of some new fields, such as the

person’s precise Birthday. All of the fields are

optional, even the name - so you can start with a very broad search and narrow

down by adding more information.

Tip: less is more when it comes to searching at

Findmypast - the less information you enter on the Search form, the more

results you'll get! Should you get too many results you can always add more

information and try again.

Note that there are boxes on the form for the

National Archives references - the piece number, and the item number. I suggest

you record these for the households you purchase as they'll provide a quick way

of finding the record again. And who knows, perhaps one day we'll add the 1939

Register to the list of censuses supported by LostCousins?

The Address search is identical to the census

address search, and uses the same form. Look for Search

addresses in the main Search menu.

Pitfalls to avoid when searching by address

Searching by address sounds simple, but there are

some complicating factors that you need to be aware of:

- Postal addresses can be a

misleading guide to the Borough/District - for example, I grew up in

Chadwell Heath, Romford as far as the postman was concerned but we were in

the adjoining borough of Ilford for the purposes of voting and rates. I

didn't find this out until quite recently.

- There might be more than one

street in a borough with the same name - this is most likely to be a

problem with common names like Station Road, or London Road.

- Some address information was

omitted when the records first launched in November 2015, and whilst this

has been addressed (pun intended) the problem might persist in a few

instances. When you search for a street you can

view a list of all the houses that have been indexed - even if there is a

gap in the numbering it's likely that the occupants of those properties

can still be found by name.

- Streets may have been renumbered or renamed.

Closed

records are NOT indexed

Some records are closed to protect the privacy of the individual

– this applies to records for anyone born less than 100 years ago (unless their

death has been recorded and linked to the relevant record). Closed records can

usually be opened by submitting a death certificate, but you need to know where

the individual was living in 1939.

If a record is closed then you won't find that

person in the index, no matter how you search. For example, when the register

first launched my mother was not in the index (because she was born less than

100 years go), and since she had been evacuated I didn't know where she was living, so couldn’t

simply submit her death certificate.

Fortunately Findmypast opened an additional 2.5 million records

in December 2015, having used a sophisticated algorithm to match death index

entries against register entries - this was possible because the death indexes

from 1969 onwards include the individual's date of birth. Millions more records

have been opened subsequently.

There are still many records which are closed, even

though the person is now deceased - unfortunately the National Archives, who

hold the registers, and have ultimate responsibility for deciding which records

can be opened, have to take a conservative approach to

avoid breaching the privacy of living people.

However if you can work out where someone was living, and

have their death certificate, you can open the record. You can see an example of

the form here.

How to work

out who the hidden people were

When you view the handwritten images you see an entire

page – other than the closed records, which are blanked out. Usually

the inhabitants of a household are listed in the same way that they would be on

a census, starting with the father and continuing with the mother and the

children in descending order of age; lodgers and visitors are likely to be at

the end.

You won't always be able to see where one household

ends and the next begins, but you can easily work it out from the way in which

the entries are numbered. Remember, you know how many open and how many closed

records there are in a household from the transcription (it isn’t always

obvious from the image of the register page).

This means that in most cases you'll be able to work

out whose records are hidden, by combining what you can see or deduce with your

own knowledge of the family.

Tip: in a few

cases you might see a small part of a closed record - perhaps the descender

from a letter 'y', 'g', 'p', or 'j'. The position of the descender may help to

confirm that the hidden person was named 'Mary', or 'George'.

Who should

we be looking for, and why?

Often the most interesting revelations are going to

come from researching people who aren't close relatives. For example, as

mentioned above, I discovered one of my Dad's cousins

living with a man who wasn't her husband, and that solved several mysteries for

me. It also indirectly enabled me to identify several cousins who are still

living – so much from just one household!

I also found it interesting looking at neighbours,

some of whom I remembered from my childhood in the 1950s – and I discovered a lot

that I hadn't known about a family friend who my mother had worked with during

the War.

How much you learn will depend not so much on how much

you already know, but on how open you are to making new discoveries - indeed,

the more you know, the easier it will be to expand your search outwards, to

more distant relatives. What you find in the register won't be an end in itself, but a gateway to yet more information - once

you know precisely when someone was born it's usually easy to find their death

(assuming they died in England or Wales between Q3 1969 and 2007), and that

makes it easier to fill in the gaps in between.

The rather fuzzy photo on the right is the only known

image of the opposite page of a register - we normally only see the left-hand

page and the first column of the right-hand page. I grabbed this shot from a

video on the Findmypast blog, and whilst it’s hard to make out any of the

detail you can get an impression of the sort of notation you might find (given

the opportunity).

The rather fuzzy photo on the right is the only known

image of the opposite page of a register - we normally only see the left-hand

page and the first column of the right-hand page. I grabbed this shot from a

video on the Findmypast blog, and whilst it’s hard to make out any of the

detail you can get an impression of the sort of notation you might find (given

the opportunity).

I have a copy of my own record from the NHS Central

Register, from which I've been able to deduce that many, perhaps all, of the

notes relate to people moving from one NHS area to another. (I'd be interested

to hear from anyone else who has obtained a facsimile copy of their entire

index entry - often you only get a printout.)

Fortunately we're probably not missing out on very much by not

seeing that right-hand page - frustrating as it is not to be able to see it!

Why do some people have two

entries

Although we can’t see the entries on the right-hand page,

we do know that sometimes the relevant line was so full that a complete

new entry had to be started. You’ll see this most

often for younger people – not only do young people tend to move more, but they

were also likely to have lived longer after 1939.

Generally the continuation entry is at the back of the same

register, but if there was no space left in the register the entry would

continue in a different register. Note that the address given won’t be the one

at which the person was living at the time the continuation entry was created,

but the one at which they were originally recorded in 1939.

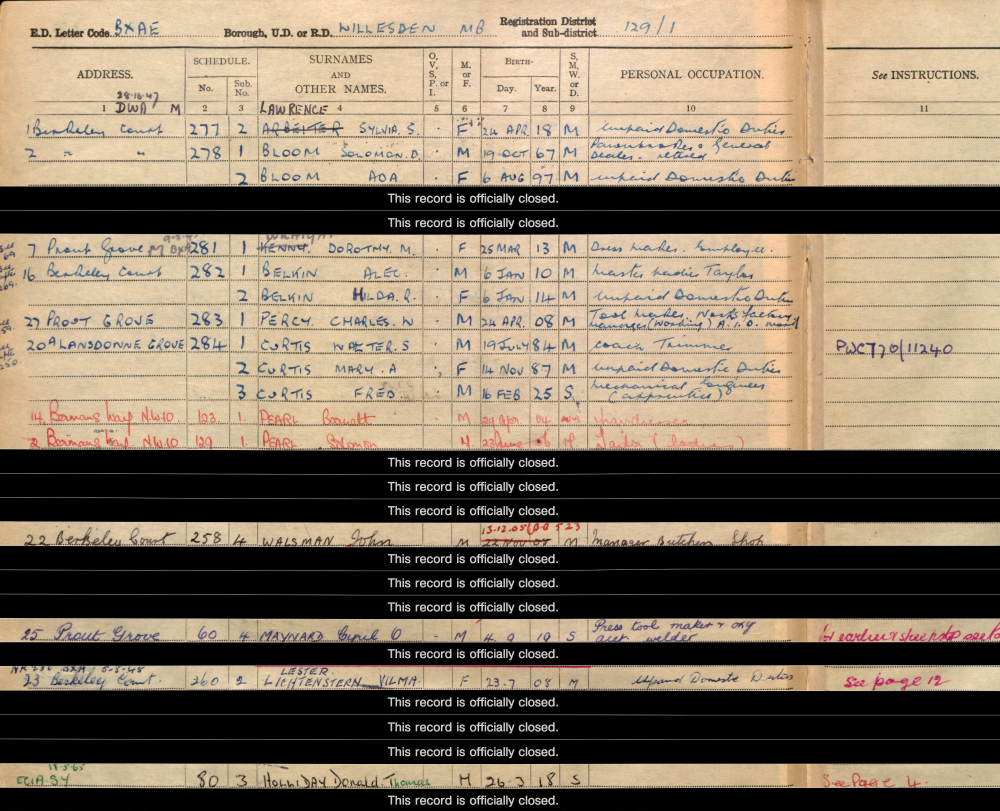

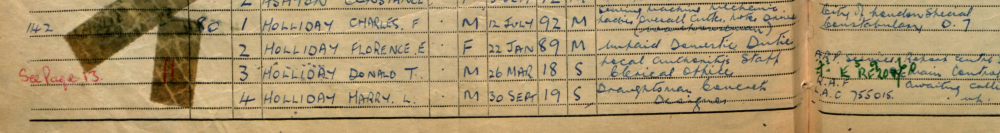

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

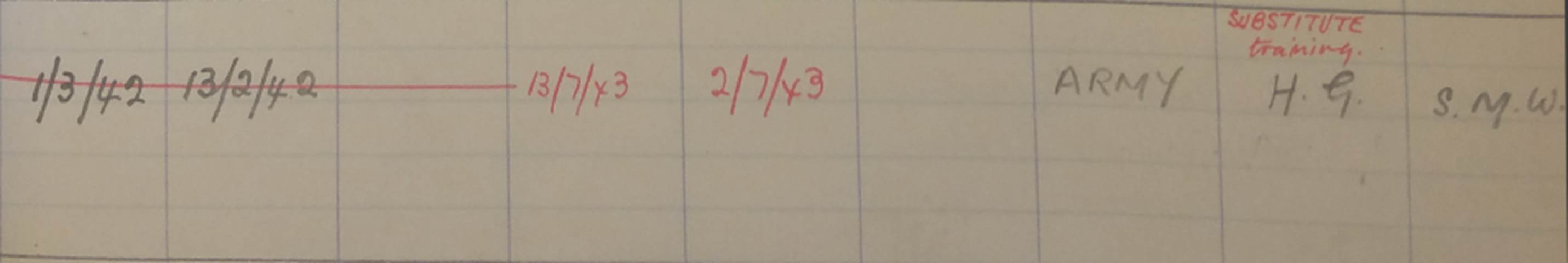

The image above shows the last non-blank page of one

of the registers: the entries in red are the first continuation entries – the

fact that the schedule numbers are out of sequence confirms this. And the fact

that most of the continuation entries are still closed is evidence that they were

born less than 100 years ago, so would have been children in 1939. (Of course,

when the 1939 Register was first released online in 2015 some of the closed

entries would have related to adults.)

Here is the original entry for Donald Thomas Holliday,

on page 4 of the register:

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

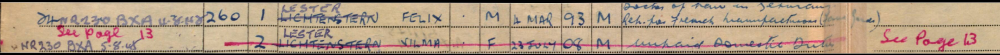

Note that his full middle name is only shown in the

continuation entry. The entry for Velma Lichtenstern is an interesting one – on

page 13 it’s not immediately obvious that her surname has changed from ‘Lichtenstern’

to ‘Lester’, but the original entry on page 12 makes this clear:

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

Always look at both the original and the continuation

entry – the information will often differ, and that will be a story in itself.

Insights we

can get from identity cards

Although it has many things in common with a census,

the 1939 Register for England & Wales is at heart a list of identity cards

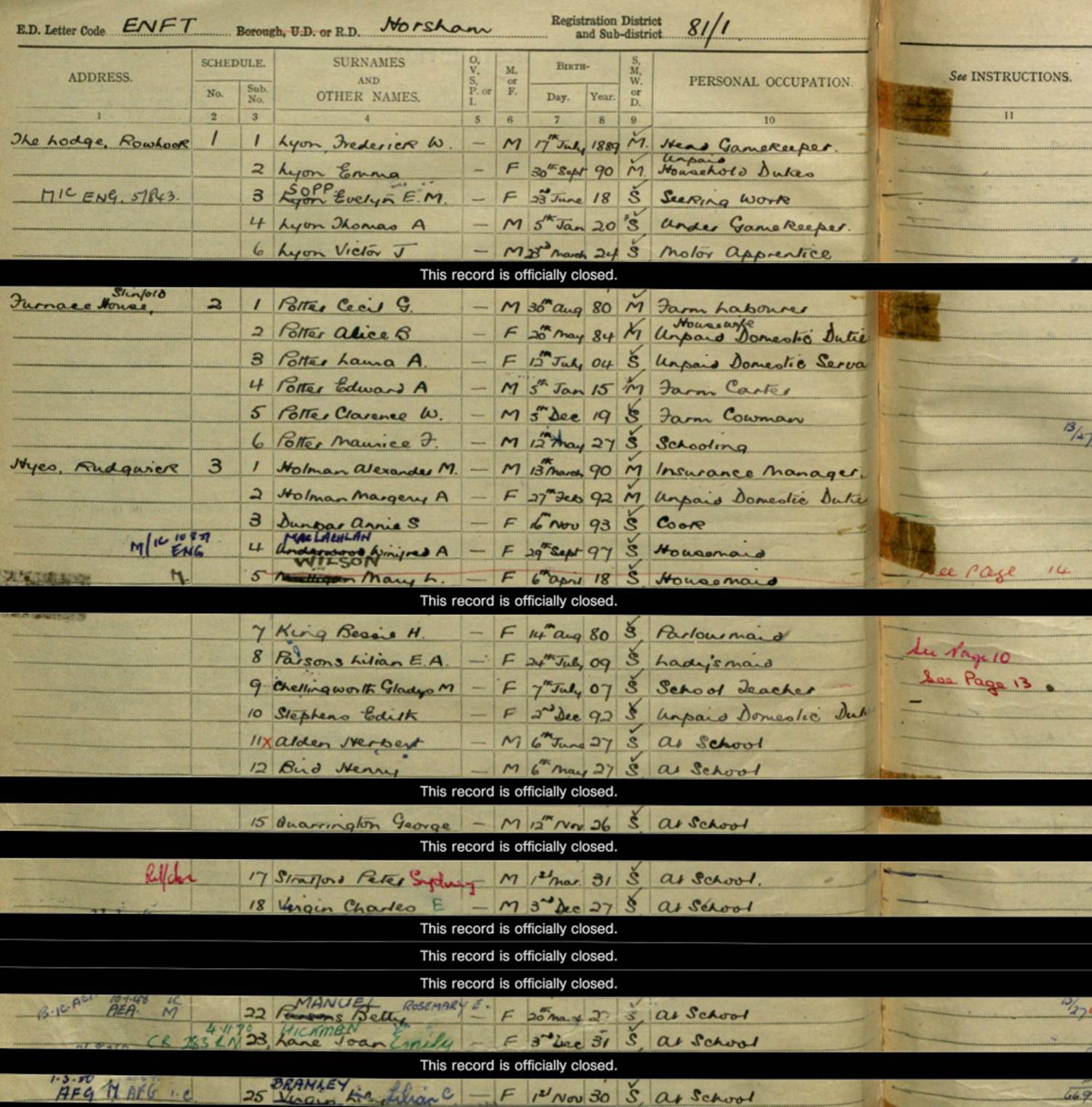

issued, together with the names and details of the holders. Take

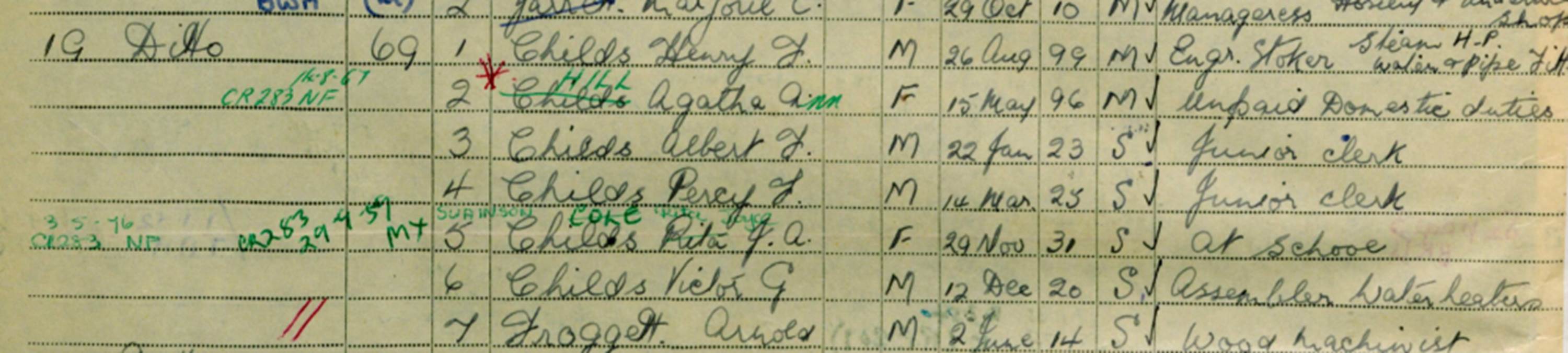

a look at this extract from the register:

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

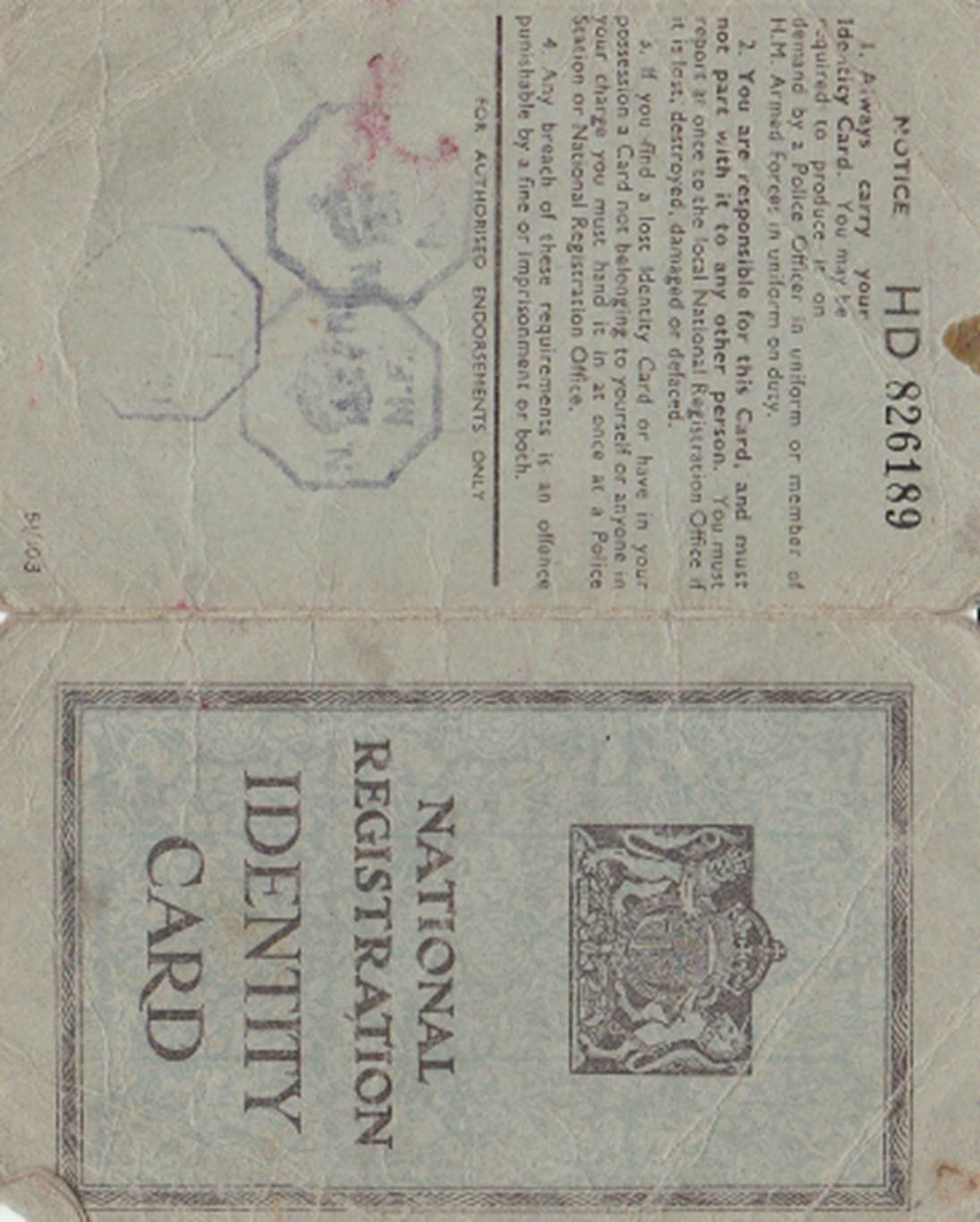

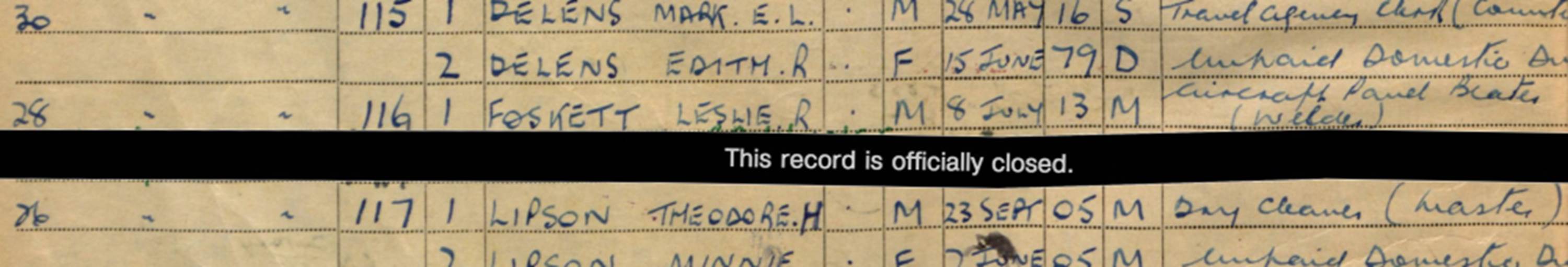

Note the Enumeration District letter code at the top

left – ENFT. This formed the first part of the Identity Card number for every

person in that district, and comprised a three letter

code (ENF) for the borough or district, in this case Horsham, followed by a

single letter (T) identifying the specific enumeration district.

The second part of the number was made up of the

Schedule Number and the Sub-schedule Number. For example, the number of the

Identity Card issued to the first person on the page, also the first person in

the Enumeration District, was ENFT 1:1 whilst the number for the last person in

this extract was ENFT 3:25

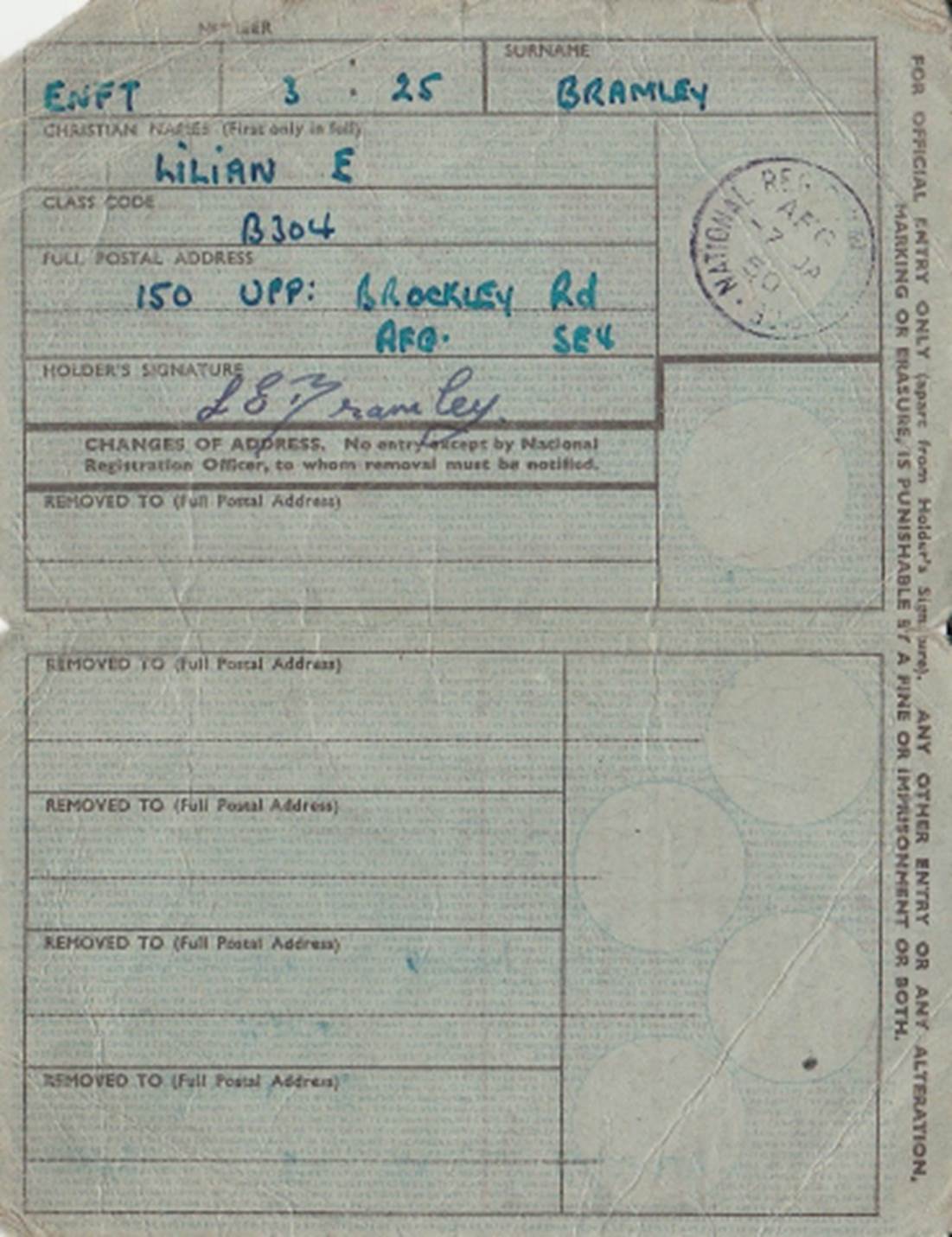

Thanks to LostCousins member Mike I'm able to show you

the Identity Card for Lilian Bramley, which confirms that her number was indeed

ENFT 3:25

This isn't, of course, the Identity Card she was

issued in 1939 - it has her married name, and her new address, But the number

of the card is exactly the same, because that's how

the system worked. If you go back to the 1939 Register entry

you'll see that it shows the date in 1950 that the register was updated,

probably 1/3/1950, and also a three letter code AFG, which also appears on the

Identity Card. This is the three letter for Deptford,

the borough to which she had moved.

Tip: you'll

find a table of boroughs and their three letter codes here (although it isn’t complete).

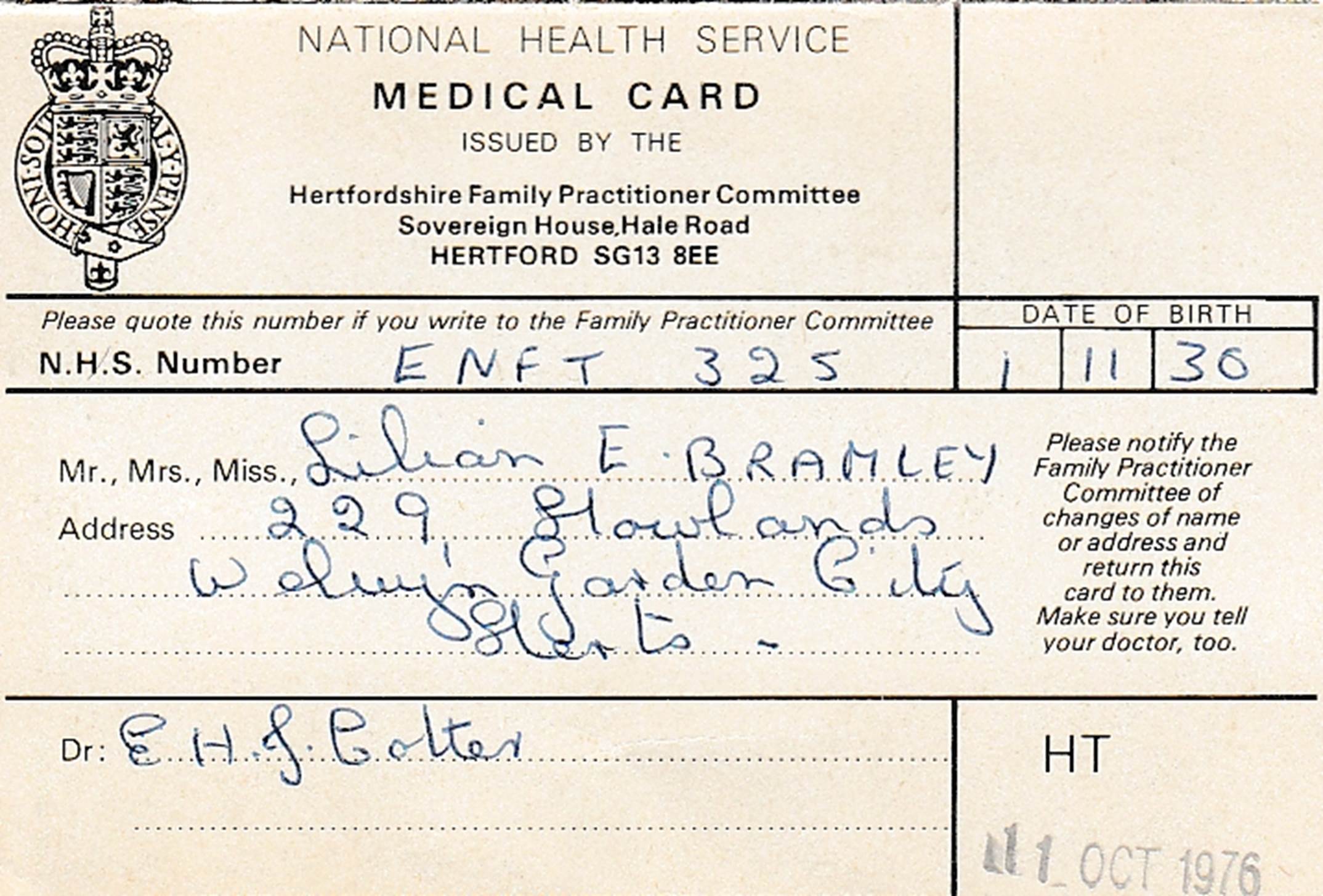

When the National Health Service launched in 1948 it

was natural to use the same numbers to identify patients, and although identity

cards were abolished in 1951 (the circumstances are described in this BBC News article),

the National Register was repurposed as the NHS Central Register until it was

eventually computerised in the decade up to 1991. And, as you can see from the

Medical Card below, which was issued in 1976, Mrs Bramley still had the same

number, with its Horsham borough code, even though she had by now relocated to

Hertfordshire.

In the second part of this article - which follows -

I'll be looking at another example of how Identity Card numbers were used, both

during and after the war.

Note: something

that won't be apparent from the register page is that the maiden name of

Margery Holman, the lady of the household where Lilian was staying, was Boot -

she was the youngest daughter of Jesse Boot, the founder of Boots the Chemist.

Isn't it amazing what we can find out if we only look?

How the numbers from identity cards were used

![]() In the previous article I described how the numbers on

identity cards came about, and explained that – whilst

the numbers were originally based on a

person's whereabouts in September 1939 - they didn't change when someone moved

house, or even when a woman acquired a new surname as a result of her marriage.

Indeed, because – in England, at least – the same numbers were used for NHS

cards even after identity cards were abolished at the end of 1951 some people

kept their numbers for half a century.

In the previous article I described how the numbers on

identity cards came about, and explained that – whilst

the numbers were originally based on a

person's whereabouts in September 1939 - they didn't change when someone moved

house, or even when a woman acquired a new surname as a result of her marriage.

Indeed, because – in England, at least – the same numbers were used for NHS

cards even after identity cards were abolished at the end of 1951 some people

kept their numbers for half a century.

Now I'm going to show how identity card numbers –

references from the 1939 Register – were used by employers during World War 2,

focusing on The Preston Sheet Metal Co. in Willesden, north

west London since I acquired some of their records at an auction). In

the process I'll provide some examples from the company's own records, and then

show the corresponding entries in the 1939 Register.

The chances are that someone reading this newsletter

will be related to one of the people who worked for the company but as the

examples I've chosen all related to open records in the 1939 Register I don't

think that I'll be intruding on anyone's privacy. (Either way, I'd be very

interested to hear from anyone who knows of the company.)

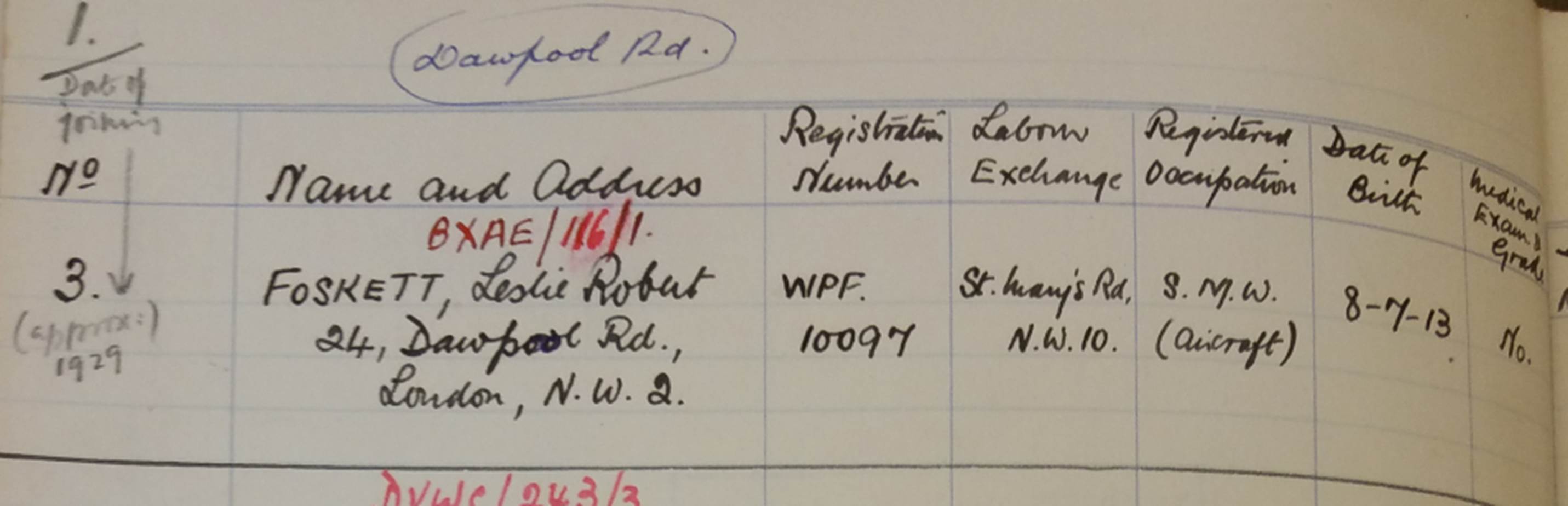

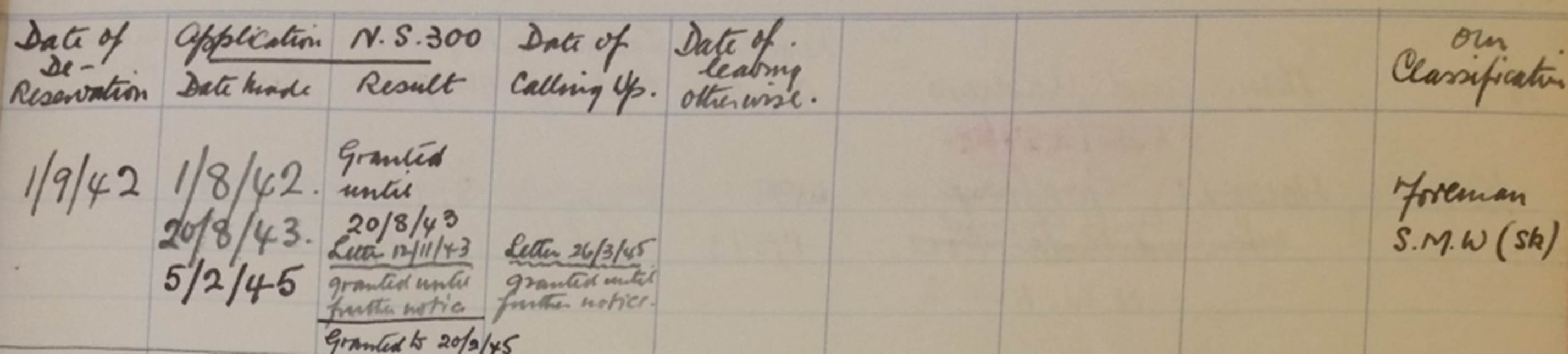

© Image

copyright Peter Calver 2017-2024 All Rights Reserved

The book I discovered hidden amongst the photo albums

of the auction lot contained handwritten records of employees - and the very

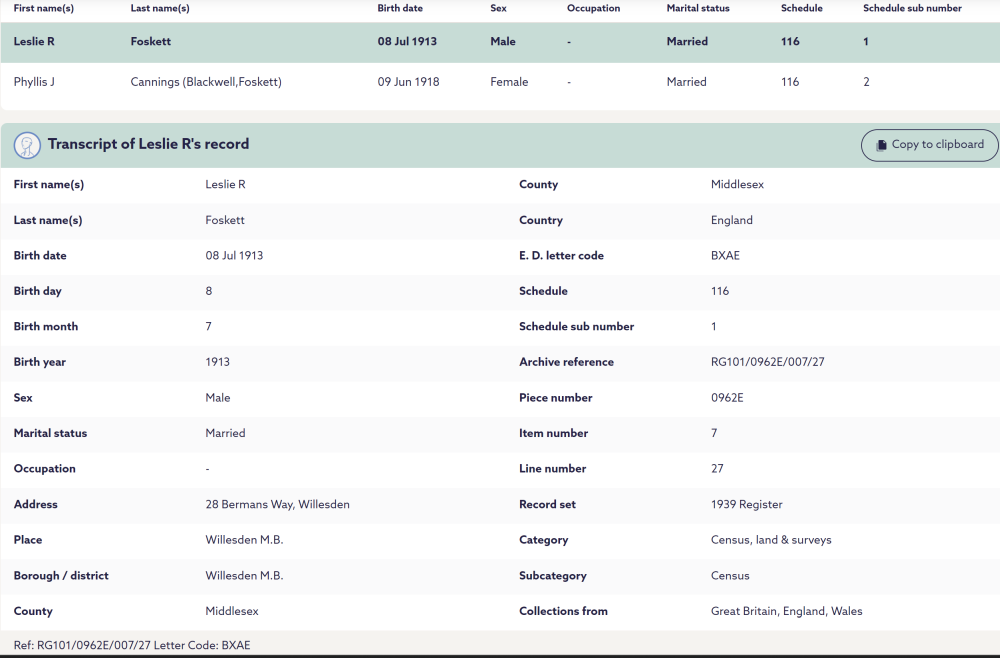

first entry was for Leslie Robert Foskett who joined the company c1929 when he

would have been 16 years old. My next step was to search the 1939 Register,

looking for a Leslie Foskett born around 1913 - and there was only one:

Note that whist the address is different, the Letter

Code, Schedule, and Schedule Sub Number (BXAE/116/1) match the information

given in the company's records. And we now know what sort of products the

company was producing - panels for aircraft.

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast (image generated 2017)

When this guide was first published in 2017 there was

an intriguing closed entry in the register immediately

below the entry for Leslie Foskett. A search of the GRO marriage registers

showed that in the second quarter of 1939 Leslie R Foskett married Phyllis J

Payne, and since there was someone of that name whose birth was registered in

Willesden in 1918, I deduced that the closed record related to her, and you can

see from the transcription that my hunch proved correct.

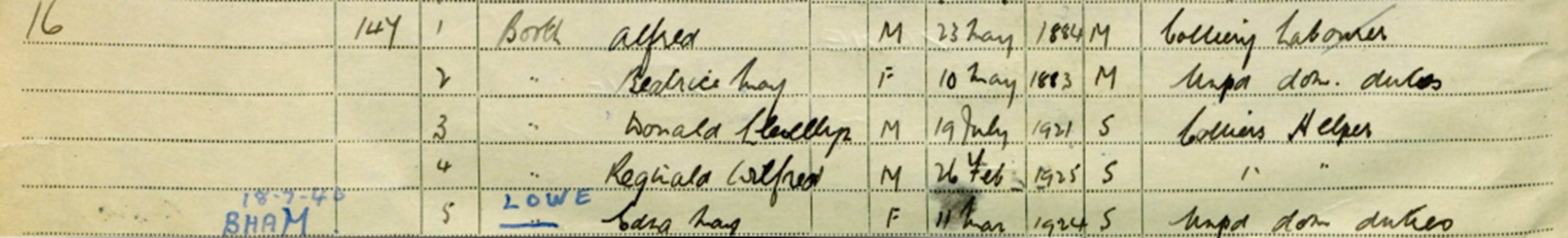

Going back to the records of The Preston Sheet Metal

Co. you'll notice that there is a column headed 'Registration Number', and that

the reference shown for Leslie Foskett is WPF 10097. Looking at the other

entries I noticed that these references only appear when there is an entry in

the 'Labour Exchange' column, so I suspect that they have nothing to do with

the 1939 Register or identity cards, but might

indicate an employee who was sourced from the relevant exchange (these

establishments still survive, but we now call them 'Job Centres').

Most of the entries attributed to the St Mary's Rd

exchange are prefixed WPF, though a few have the prefix EXX, and I spotted one

HFL - perhaps someone reading this article will be able to interpret these

references?

As with the 1939 Register there's a right-hand page in

the book of employee records, but this time we can see what it says:

© Image

copyright Peter Calver 2017 All Rights Reserved

This suggests that whilst Leslie Foskett was in a

'reserved occupation' at the start of the war, in 1942 he became liable to

being called-up for military service - though he seems to have avoided it,

judging from the notes. But not everyone working for the company was as

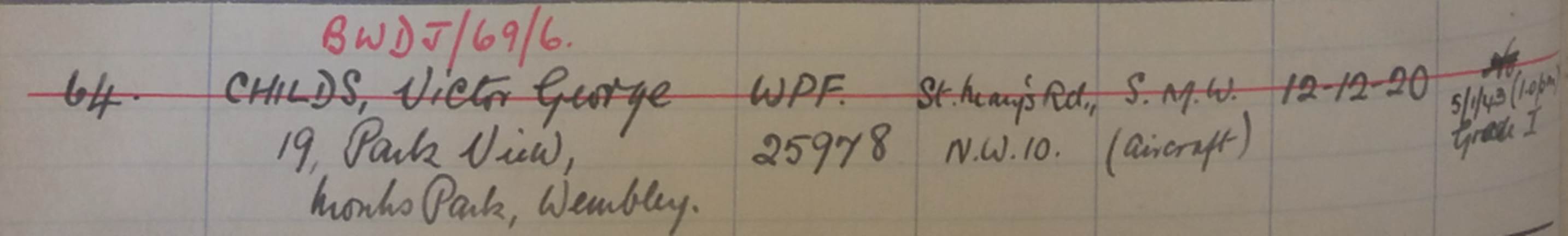

fortunate - Victor George Childs was called up in July 1943:

© Images

copyright Peter Calver 2017 All Rights Reserved

You can see his entry in the 1939 Register below -

note that he was working as an assembler of water heaters in September 1939:

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

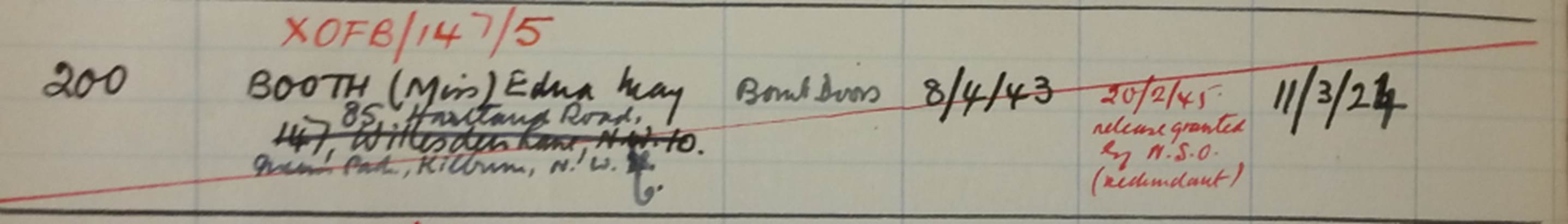

Of course, The Preston Sheet Metal Co. didn't only

employ men - there was a war on, and everyone had a part to play, including

Edna May Booth, who worked in the Bomb Doors department:

© Image

copyright Peter Calver 2017 All Rights Reserved

As you can see from her identity card number she wasn't a local - in September 1939 she'd been

living with her family in Bedwellty, Monmouthshire:

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

But coming up to London did have its benefits - in

1946 Edna married Frank H Lowe. Edna died in 1971, just as they would have been

celebrating their Silver Wedding.

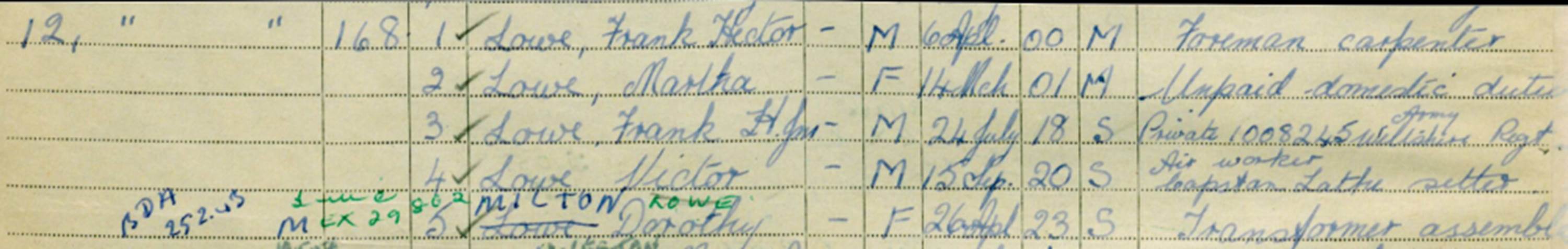

Without ordering their marriage certificate I can't be

sure who her husband was, but I'd like to think that this was him, living in

Edmonton, Middlesex (north east London):

© Crown

Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London,

England and Findmypast

This is a rare example of a serving soldier recorded

in the 1939 Register - I imagine he was home on leave. Frank Hector Lowe junior

lived until 2003, and died in Hackney registration district, not far from where

he was living in 1939 or from where Edna died in 1971.

Track down evacuees using LostCousins

The evacuation of millions of British

schoolchildren during World War 2 will have had a lasting effect, not only on

their lives, but also on the lives of the families with whom they were

billeted. Having found my mother on the 1939 Register I wondered how feasible

it would be to track down members of the family she lived with - and realised

that one way of doing this would be to use the My Ancestors page....

Whilst you can't enter people from the 1939

Register on your My Ancestors page (at least, not at the moment), many of them will also have been recorded on

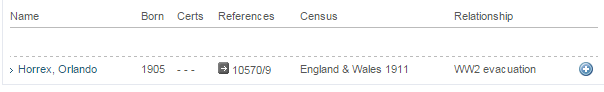

the 1911 Census. I've therefore created a new category in the Relationship

or category dropdown menu - WW2 evacuation - so that I and other

members can search for relatives of the people who looked after the evacuees in

our families during the war.

Here's the first ever entry using this new

category:

I'll let you know if I get a match! In the

meantime, why not see who you can find?

How evacuation was planned in 1939

In 1939 each area of the country was assigned one

of three roles:

- Evacuation

- Reception

- Neutral

I was fortunate to find a document online at the HistPop website which details which areas came into

which category, and I suspect many of you will find it very interesting to look

up the areas where your family lived. It's about 12 pages long - use the Previous

Page and Next Page links at the bottom to navigate;

my understanding is that areas not specifically mentioned were Reception areas.

Of course, trying to predict which parts of the

country would be safe from the Luftwaffe wasn't a precise science - one member

wrote to tell me that his family moved "out of the frying pan into the

fire" when they relocated!

When Britain declared war on Germany in September

1939 it was a sad day, but it wasn't a surprise. Evacuation forms were

circulated to parents as early as May 1939 (see the article below about Operation Pied Piper), and it turns out

that plans for the issue of identity cards were being formulated as early as

1st December 1938, when the General Register Office circulated a memorandum to Registrars of Births and

deaths about:

"proceeding immediately

with certain of the preparations for the 1941 Census, as a means of providing

for the institution of a National Register at very short notice, should a

national emergency arise."

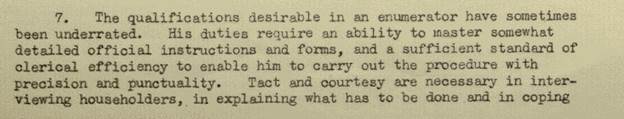

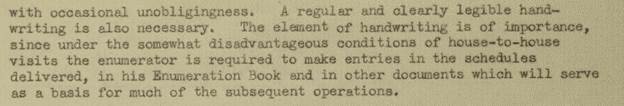

Qualifications desirable in an enumerator

When a further memorandum went out from the General

Register Office on 6th January 1939 it stated that:

When you've seen as many pages from the National

Register as I have, you'll know that the enumerators didn't always live up to

those high standards - even handwriting that appears neat can be hard to read

if the letters are written inconsistently, or confusingly.

The fact that subsequent amendments to surnames

were made in block capitals suggests that even at the time the handwriting was

causing problems.

With the threat of war looming, the British

Government prepared plans for mass evacuation. During WW1 Germany had bombed

London and other targets using Zeppelin airships (you can read more about

it here), but now the enemy had modern bombers

(over 1000 were operational by September 1939), and the bombing of Guernica in 1937, during the Spanish

Civil War, had demonstrated the devastation that could be wrought. Preparations

started long before the war: this form headed Government Evacuation Scheme is

dated May 1939 - note that mothers were asked if they wanted to go with their

children.

Operation Pied Piper went into action on 1st

September 1939, two days before Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister

made his momentous radio broadcast to the nation:

"This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German

Government a final Note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock

that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state

of war would exist between us.

"I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received,

and that consequently this country is at war with Germany."

![]() Children had assembled in school playgrounds on the

morning of 1st September, each with a luggage tag attached to their coat, and

carrying bare necessities: their gas mask, underwear, pyjamas or nightdress,

plimsolls, toothbrush, comb, soap, and a face flannel. Over half a million

children were evacuated from London alone during September, and my mother -

then 13 years old - appears to have been one of them, because on Registration

Day (29th September) she wasn't at home with my grandparents.

Children had assembled in school playgrounds on the

morning of 1st September, each with a luggage tag attached to their coat, and

carrying bare necessities: their gas mask, underwear, pyjamas or nightdress,

plimsolls, toothbrush, comb, soap, and a face flannel. Over half a million

children were evacuated from London alone during September, and my mother -

then 13 years old - appears to have been one of them, because on Registration

Day (29th September) she wasn't at home with my grandparents.

Over the course of just three days around 1.5

million mothers and children were sent from towns and cities into the

countryside, mostly by train - you might this Southern Railways poster interesting. However, because

bombing raids on cities didn't materialise in the first few months of the war,

many children went back home - over half had returned by January 1940, despite

Government warnings (I believe my mother was one of

them).

There were further waves of evacuation during 1940,

and my mother's school was evacuated toFinnamore Wood

Camp, Marlow, Buckinghamshire on 22nd April - you can see a

photo here which shows some of the schoolgirls.

My mother wasn't amongst them, however - my grandmother wouldn't allow her to

leave home again - and so my mother left school and spent the duration

supporting the war effort, mostly working at the nearby Ship Carbon factory, which

made carbon rods for cinema projectors and searchlights.

A smaller number of children were evacuated

overseas, a story told in the book Out of Harm's Way, written by an evacuee -

but this programme came to end when the SS City of Benares was sunk in

September 1940, killing most of the children on board. However

some children were evacuated privately even after this incident.

In 1939 the country was divided into more than 1400

administrative areas, each of which was assigned a three

letter code, such as CJL for Bromley in Kent and ZDJ

for Portmadoc in Caernarvonshire (larger

areas may have had more than one code, in which case the code in the table is

the first in the block). When you find one of your relatives

you'll see that a fourth letter has been appended to the end - this specifies

the enumeration district.

You will find a table of codes and areas here.

When, in February 2007, I asked to inspect the 1939

Register under the Freedom of Information Act I was rebuffed by the Office for

National Statistics – it's covered by the 1920 Census Act, they claimed.

Absolute rubbish, but for a while they got away with it, whilst I went through

the appeals process. Then I got a phone call from the Information Commissioner's

Office to tell me that whilst they were minded to allow

my appeal, the records had been transferred from the ONS to the NHS, so the

whole process would have to start again!

Unfortunately by this time my father, who was in his 90s, was

becoming frail and I was having to look at care homes – I just couldn't spare

the time to do it all again. But fortunately I wasn't

the only one trying to get access to the Register, and eventually, thanks to

the efforts of the late Guy Etchells and others, it was agreed to provide

information from the Register, subject to a fee of £42 per household (which

wasn't refundable under any circumstances).

Then, in March 2014, came the moment that family

historians had been waiting for – Findmypast announced that they had signed a

deal with the National Archives which would see the register becoming available

online within 2 years. They beat the deadline comfortably!

· Middle names are not always shown, only initials

(even though it would appear that full middle names

were recorded on the original household schedules)

· Closed records are NOT indexed, so will not show up

in searches, nor will people who were in army barracks or similar institutions

(for example, Alan Turing is not listed – presumably because by September 1939

he was already at Bletchley Park)

· The register pages are like the enumerators'

summaries that we see for the censuses up to 1901 – the entries have been

copied from the schedules completed by the householders, so we don't get to see

our ancestors' handwriting

· The references displayed are in this format

Ref: RG101/1100C/019/36 Letter Code: CCVZ

where RG101 is the National Archives reference for the

1939 Register (this doesn't change)

1100C is the piece number

019 is the item number (it identifies a specific page but I

couldn't see the number in the image)

36 is the line number on the page - again it's not shown, but you

can count down

The Letter Code refers to the area - there's a guide to these codes in

the TNA blog, and also see above

· You're also given the Schedule Number and Schedule

Sub-Number but can't search using this information; people in the same

household have the same Schedule Number (the Sub-Number is the line on the

Schedule, usually 1,2,3,4 etc)

· Make a note of the references - they'll enable you

to find the page again instantly (and you never know, one day we might use

these records at LostCousins!)

· National Registration Day was 29th September 1939,

but someone who is listed may not have arrived until the next day (assuming

they were not registered elsewhere)

· 'Unpaid DD' means 'Unpaid domestic duties'

· The register was a working document - though it was

created in 1939 it was amended and annotated as people moved, married, and

died; most of the annotations are on the right-hand page, where we can't see

them, but there are some on the left-hand page (see below for a guide to

abbreviations)

· Sometimes a woman's surname will have been crossed

out and another surname written in - this is usually a name change on marriage;

in the Search results the surname in 1939 will appear in brackets; if there are

more than two surnames all but the most recent will be in brackets

· In these cases you can

search on any of the surname (you don't have to tick the surname variants box),

but the entry you want probably won't be at the top of the

search results because of the way they are sorted

· If you're very lucky you may find someone whose

name changed on adoption (they would have had to be adopted after the creation

of the register, otherwise you wouldn't see the birth name)

· On the right hand side of

the register you can sometimes see a note such as 'ARP warden'

· You might see an alias recorded, for

example one 'Harry' was noted as 'o/w Henry'

· Occasionally the date of death is recorded on the right hand page - check it against the GRO indexes to make

sure

· My aunt's year of birth was erroneously transcribed

(by the enumerator) as '76' rather than '16' which meant her record was open at

launch when it should have been closed – had she still been with us she would have

been absolutely delighted!

· Sometimes you'll see a note such as "See page

14"; in this case there will usually be an arrow to the left or right of

the image - click the arrow to see the other record

· When there isn't an arrow you are likely to find

the individual listed twice in the Search results

· If your relative was in an institution of some kind

you should be able to see all of the pages relating to

that institution by clicking the left and right arrows

©

Copyright 2017-2024 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the

website are affiliate links – if you make a purchase after clicking a link you

may be supporting LostCousins (though this depends on your choice of browser,

the settings in your browser, and any browser extensions that are installed).

Thanks for your support!