Newsletter - 2nd February 2018

Free access

to UK censuses & BMD records ENDS THURSDAY

How to research your family tree - a Beginner's Guide

MASTERCLASS:

finding birth certificates

Mother's

names to be on marriage certificates?

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published

2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous newsletter (dated 27th January)

click here; to find earlier articles use the

customised Google search below (it searches ALL of the newsletters since

February 2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

Whenever

possible links are included to the websites or articles mentioned in the newsletter

(they are highlighted in blue or purple and underlined, so you can't miss

them). If one of the links doesn't work this normally indicates that you're

using adblocking software - you need to make the LostCousins site an exception

(or else use a different browser, such as Chrome).

To go to the main LostCousins website click the

logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join -

it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition

of this newsletter available!

Free access to UK

censuses & BMD records ENDS

THURSDAY

Until Thursday 8th February

all UK & Ireland censuses and civil BMD records will be free at Findmypast.co.uk and Findmypast.ie

- itís not only great opportunity for you to add twigs to the branches of your

family tree, itís also a chance for beginners to get started on this wonderful

hobby of ours.

To find out more follow this link. Also free are 3000 records relating to

suffragettes (and they'll continue to be free until International Women's Day

on 8th March).

Tip: although the article on the Findmypast

site talks about searching for female ancestors, you can search anyone,

irrespective of their gender or their relationship to you,

If you tell friends and

relatives about this offer please ask them to use the

link in this newsletter - you'll be helping to support LostCousins

- and direct them to the Beginners Guide

(see the next article).

One key resource that isn't

included in the offer is the 1939 Register - but don't despair, you can learn

quite a bit from a free search.

How to

research your family tree - a Beginner's Guide

On Tuesday I was chatting

with a friend in our village when he asked me whether I might be able to find

out something about his great-grandfather.

Well, I don't need to be

asked twice - and after just half an hour's online research I'd not only found

out who his great-grandfather was, what he did for a living, and who he

married, but taken the line two generations further back, all the way to my

friend's great-great-great grandfather, who was born in 1797.

My friend was amazed and

delighted, though it as far I was concerned it could have worked out better: since

my friend's father was a butcher and his grandfather was

a baker, I was rather hoping his great-grandfather was going to turn out to be

candlestick-maker - what a great anecdote that would have made!

Researching a family tree

really can be that easy - provided you know what to do and have access to the

key online resources. As you'll have read in the previous article, Findmypast are providing the records, so it only remains

for me to direct you to the Beginner's Guide on the Help & Advice

page at the LostCousins site - itís called Research your British ancestors - the SMART

way!

One of the first things we

learn as family historians is that names are fickle things - in England one can

change one's name from Montague to Capulet without any legal formalities,

although for practical reasons many people of substance execute a deed poll

(which is a generic term for a deed which has no counter-party - by contrast a

contract always involves at least two parties).

I can remember that when I visited

the Family Records Centre in Islington in days of yore they had on the wall a framed

copy of the deed executed by Reginald Kenneth Dwight when he changed his name

to somewhat more melodious Elton John.

When a couple marry itís usual for one of them, usually the bride, to change

their name - though it has been fashionable for a number of years to adopt a

double-barrelled surname, But it's still quite rare for a man to take his wife's

name on marriage, which is why this story made it onto the

BBC news website.

But itís not a completely new

phenomenon: when my late 2nd (and 3rd) cousin Howard Horace Lemmon married in

1951 he took his wife's name, something that for many years prevented me finding

the births of their children. Some people who donít like their surname adopt

their mother's maiden name. but that may not have been something that Howard seriously

considered (his mother was a Duck).

MASTERCLASS: finding

birth certificates

It's very frustrating when you can't find an ancestor's birth

certificate - but often the 'brick wall' only exists in our imagination. Let's

look at some of the key reasons why a certificate can't be found....

∑ The

forename you know your ancestor by may not be the one on the birth certificate

Sometimes the name(s) given at the time of baptism would differ

from the name(s) given to the registrar of births; sometimes a middle name was

preferred, perhaps to avoid confusion with another family member, often the

father. Although it was possible to amend a birth register entry to reflect a

change of name at baptism, most people seem not to have bothered.

There can be all sorts of reasons why a different forename is used - one of my

ancestors appears on some censuses as 'Ebenezer' and on others as 'John' (which

I imagine was the name he was generally known by). In another family the

children (and there were lots of them) were all known by their middle names.

∑ Middle

names come and go

At the beginning of the 19th century it was rare to have a middle

name, but by the beginning of the 20th century it was unusual not to have one. Some

people invented middle names, some people dropped middle names they didn't

like, and sometimes people simply forgot what was on the birth certificate.

For example, one of my relatives was registered as Fred, but in 1911 his father

- my great-grandfather - gave his name as Frederick.

∑ The

surname on the certificate may not be the one you expect

If the parents weren't married at the time of the birth then

usually (but not always) the birth will be recorded under the mother's maiden

name (the exception is where the mother was using the father's surname and

failed to disclose to the registrar that they weren't married).

Also bear in mind the possibility that

the surname you know your ancestor by was his stepfather's name - this could

apply whether or not the child was born outside marriage.

∑ You're

looking for the wrong father

Often the best clue you have to the identity of your ancestor's

father is the information on his or her marriage certificate. Unfortunately marriage certificates are often incorrect -

the father's name and/or occupation may well be wrong. This is particularly

likely if your ancestor never knew his or her father, whether as a result of early death or illegitimacy. Not many people

admit to being illegitimate on their wedding day - and in Victorian Britain

illegitimacy was frowned upon, so single mothers often made up stories to tell

their children (as well as the neighbours).

Whether or not the birth was legitimate young children often took the name

of the man their mother later married, so always bear in mind the possibility

that the father whose name is shown on the marriage certificate is actually a

step-father.

∑ You

may be looking in the wrong place

A child's birthplace is likely to be shown correctly when he or

she is living at home (few mothers are going to forget where they were when

they gave birth!), but could well be incorrect after

leaving home. Many people simply didn't know where they were born, and assumed

it was the place they remembered growing up.

The most accurate birthplace is the one given by the father or (especially)

the mother of the person whose birth you're trying to track down; the least

accurate is likely to be the one in the first census after they leave home.

∑ You

may be looking in the wrong period

Ages on censuses are often wrong, as are the ages shown on

marriage certificates - especially if there is an age gap between the parties,

or one or both is below the age of consent (21). Sometimes people didn't know

how old they were, or knew which year they were born, but bungled the

subtraction; ages on death certificates can be little more than guesses, or may be based on an incorrect age shown on the

deceased's marriage certificate. Remember too that births could be registered

up to 42 days afterwards without penalty, so many will be recorded in the

following quarter - and they could be registered up to 365 days afterwards on

payment of a fine.

In my experience, where the marriage certificate shows 'of full age' it's

often an indication that in reality they were under

21!

∑ The

birth was not registered at all

This is the least likely situation, but it did happen occasionally

- most often in the first few years of registration, though it wasn't until 1875

that there was a penalty for failing to register a birth.

∑ The

GRO indexes are wrong

This is also quite rare, but did happen

occasionally despite the checks that were carried out. Fortunately

the indexes that the GRO made available on their website in November 2016 were

compiled from scratch, so many indexing errors will have been eliminated.

∑ The

GRO indexes have been mistranscribed

Transcription errors can prevent you finding the entry youíre looking

for - so donít confine your searching to a single website (none of them are

perfect).

How can you overcome these problems? First and foremost

keep an open mind - be prepared to accept that any or all of the information

you already have may be wrong. This is particularly likely if you have been

unable to find your relative at home with their parents on any of the censuses.

Obtain all the information that you can from censuses,

certificates, baptism entries and other sources (such as Army records). The GRO's

new birth indexes show the mother's maiden name from the start of civil

registration - the contemporary indexes only include this information from July

1911 onwards. And donít assume that the same information will be shown in the baptism

register as in the birth register.

The less information you can find, the more likely it is that the

little you already have is incorrect or misleading in some way. For example, if

you can't find your ancestor on ANY censuses prior to his marriage, you can be pretty certain that the information on the marriage

certificate and later censuses is wrong in some material way.

Don't assume that just because something appears in an official

document, it must be right. Around half of the 19th century marriage

certificates I've seen included at least one error, and as many as half of all

census entries are also wrong in some respect (I'm not talking about

transcription errors, by the way). Army

records are particularly unreliable - one of my relatives added 2 years to his

age when he joined the British Army in 1880, and

knocked 7 years off when he signed up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force in

1914.

Some people really were named Tom,

Dick, or Harry but over-eager record-keepers might assume that they were actually Thomas, Richard and Henry. My grandfather was

Harry, but according to his army records he was Henry (just as well he had two

other forenames, which were recorded correctly, otherwise I might never have

found him).

Consider how and why the information you have might be wrong by

working your way through the list above - then come up with a strategy to deal

with each possibility. Sometimes it's as easy as looking up the index entry for

a sibling to find out the mother's maiden name; often discovering when the parents

married is a vital clue (but don't believe what it says on the 1911 Census -

the years of marriage shown may have been adjusted for the sake of propriety).

If you can't find your ancestor on any census with his or her

parents then you should be particularly suspicious of the information you have

- it's very likely that some element is wrong, and it is quite conceivable that

it is ALL wrong.

Middle names that could also be surnames often indicate

illegitimacy - it was usually the only way to get the father's name on the

birth certificate. Unusual middle names can provide clues - I remember

helping one member find an ancestor whose birth was under a completely

different surname by taking advantage of the fact that his middle name was

Ptolemy!

Make use of local BMD indexes (start at UKBMD),

and don't forget to look for your ancestor's baptism - sometimes we forget that

parents continued to have their children baptised after Civil Registration

began. Consider the possibility that one or both of the

parents died when your ancestor was young - perhaps there will be

evidence in workhouse records. Have you looked for wills?

Could the witnesses to your ancestor's marriage be

relatives? When my

great-great-great grandfather Joseph Harrison married, one of the witnesses was

a Sarah Salter - who I later discovered (after many years of fruitless

searching) was his mother. Her maiden name wasn't Salter, by the way - nor was

it Harrison - and it was only because the Salter name stuck in my mind that I

managed to knock down the 'brick wall'. Another marriage witness with a surname

I didn't recognise proved invaluable when I was struggling with my Smith line -

he turned up as a lodger in the census, helping to prove that I was looking at

the same family on two successive censuses, even though the names and ages of the children didn't

tally, and the father had morphed from a carpenter to a rag merchant.

Remember that you're probably not the only one researching this particular ancestor - and one of your cousins may already

have the answers you're seeking. So make sure that you

have entered ALL your relatives from 1881 on your My Ancestors page,

as this is the census that is most likely to link you to your 'lost cousins'.

Finally remember that even when you find the birth certificate the

information might not be correct; for example, if the child is the youngest in a

large family consider the possibility that the mother shown on the certificate

was actually the child's grandmother. When a birth was

registered by one parent the name of the other parent could only be recorded in

the register if the parents were married (or claimed to be married); as a result some births registered by the mother named the wrong

father, and (more rarely) some births registered by the father named the wrong

mother.

Note:

you can see an example of a birth certificate which names the wrong mother here.

Mother's names to be on marriage certificates?

It's some years since David Cameron, the then Prime Minister,

promised to put mothers' names on marriage certificates in England & Wales

(theyíve always been on Scottish certificates), but it finally seems as if the

legislation might make it through parliament - see this news article.

Whilst this move towards equality is a good move - fathers have, I

suspect, always felt annoyed at being thrust into the limelight whilst their

co-parents have been able to skulk in the shadows - what the article doesn't

point out is that the change will probably lead to the end of church marriage

registers as we know them, since itís cheaper to switch to a computerised

system than replace thousands of registers. It could also mean that instead of

getting an official certificate on the day, couples who choose to marry in church

will have to wait for a computer-generated certificate to arrive in the post

(no doubt arriving while they're on their honeymoon).

CHALLENGE: can you break down this 'brick wall'?

There's nothing quite like

breaking down a 'brick wall' to provide us with the inspiration and enthusiasm

to knock down some more. Marilyn in Australia wrote to me a few years ago with

a simple question about birth certificates, but one thing led to another, and a

couple of hours later Marilyn's 'brick wall' came tumbling down!

How would you like to test

your skill and judgment by tackling the same 'brick wall'? All you have to do is find the GRO index entry for the birth of

Marilyn's grandfather, starting with the same information that she gave me.

"I am having

difficulty locating BMD records for my Long family in London about 1850-1920 -

my grandfather, born in 1896, came to Sydney in 1920. I have obtained likely

looking [birth] certificates from the GRO only to find it is the wrong person.

"My grandfather

was Frederick Leonard Long, born possibly on 31 Oct 1896 (or between Aug 1896

and Aug 1897). His parents were George, a builder (born Kensington), and Emily

(born Notting Hill); I'm trying to find her maiden name.

"My

grandfather's [Australian] death certificate says he was born at Ealing and it

says that on the 1901 census too.

"My

grandfather's siblings were George Solomon, Elizabeth, Lillian, John, and Rose.

The family may have been Jewish. On my grandfather's death certificate

it has his father's name as Emmanuel (but it shows George on John's death

certificate) and John's death certificate also has his forenames as John Levi.

In the 1911 census Rose is Rose Annie but I may have found her 1896 birth as

Rose Edie.

"It was only in

the 1901 Census that I found the whole family... I can only find Lillian and

Rose in 1911 - I can't find either parent or the other children. It is very

frustrating!"

You can solve this mystery

using nothing but free websites such as FreeBMD.

Knocking down 'brick walls'

is fun and rewarding - even when it's someone else's tree - because the

experience you gain will lead to even greater achievements in the future! This

challenge previously featured in this newsletter in 2012, but since thousands

of reader wouldnít have been members then I thought it

was worth reprinting. There are no prizes for the correct answer - and you'll

know when you've found it, so there's no need to write in,

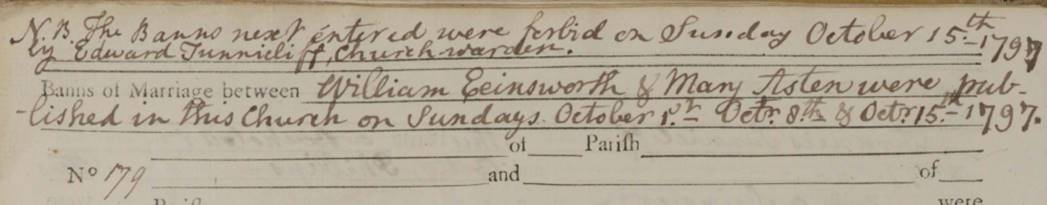

In the last

issue I gave an example of a proposed marriage where the father of the

bride interrupted proceedings at the 3rd reading of the banns, and forbade the

marriage "she being a minor".

I subsequently received some

more interesting examples, including this one from the parish of St Michael, Rocester in Staffordshire:

© Image copyright

Staffordshire County Council used by permission of Findmypast

I don't know why the marriage

was forbidden, but perhaps one of them was still married to somebody else?

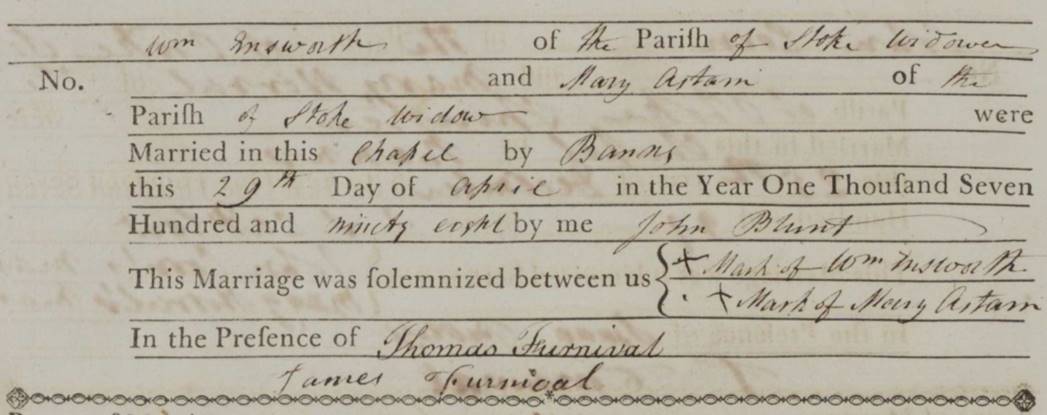

Whatever the reason, it clearly didnít stop them in their endeavour, because 6

months later they married 16 miles away in Stoke (note that on this occasion

they were shown as widower and widow - which may or may not have been the

case):

© Image copyright

Staffordshire County Council used by permission of Findmypast

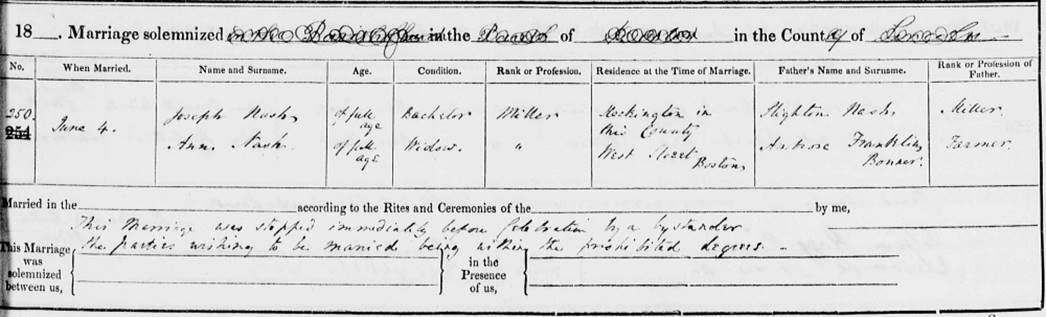

There's something remarkable

about the next entry I'd like to show you, taken from the marriage register for

St Botolph, Boston, Lincolnshire:

© Image copyright Lincolnshire

Archives used by permission of Findmypast

Although this marriage didnít

take place, because the parties were "within the prohibited degrees",

you wouldn't know that from looking at the General Register Office marriage

index, where this non-event is indexed as if it had actually

taken place!

Note: I've mischievously ordered the 'marriage'

certificate, just to see what happensÖ..

Pam, who sent in this example

- which she spotted while transcribing the register - believes that Ann Nash

may have been the stepmother of Joseph Nash. If so, the marriage would have

been illegal until the Marriage (Prohibited Degrees of Relationship) Act 1986

came into force, even though there was no blood relationship.

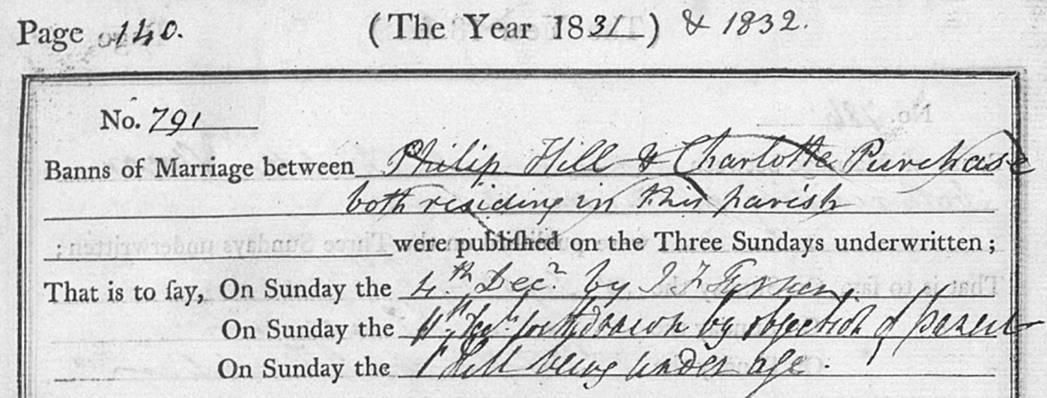

Finally an example from the parish of St Mary Major, Exeter,

Devon where the groom was under age:

© Image courtesy of South West

Heritage Trust and Parochial Church Council; used by permission of Findmypast

A couple of months later the

couple successfully married in Old Cleeve, Somerset where one of the witnesses

was Robert Darch - as some of the Darch

boys attended the same school in Tiverton as Philip Hill, it is likely that one

of Philip's old school friends helped to engineer the successful elopement.

Philip was just 17 when he married - he would have had to wait until he was 21

to marry without the consent of his father.

Although 'fake news' might

sometimes appear to be a convenient epithet for inconvenient facts, there's no

doubt that over the past two years this phenomenon has done a lot more than

simply qualify for an entry in the dictionary.

This blog article on

the BBC News charts the history of 'fake news' from its origins in a small

Eastern European town - and you might be surprised to learn which of the

candidates for US President was the first to use the term.

One of the distinctive

attributes of 'fake news' is the way that it pulls the reader in with teaser

headlines - though these have been around for longer than my lifetime, and turn

up in all sorts of august publications, including research papers and even this

newsletter (albeit in a somewhat 'tongue-in-cheek' manner).

But the defining attribute of

modern-day 'fake news' is the way it exploits social media, so that stories can

literally go around the world in minutes as gullible readers share them with a

click of the mouse or a flick of the finger - although perhaps 'gullible' is

the wrong word, since many of those who are involved in spreading these viral

infections don't seem to care whether the stories are true or not.

In the past couple of the

weeks both Facebook and the British Government have announced plans to tackle

'fake news' (you can read about them here and here). I think I know

which is most likely to be effective, but I do find it interesting that they've

both chosen to get on top of this problem at the same time.

In the next article I'm going

to once again tackle the issue of 'fake news' in the world of genealogy,

because I believe there is an interesting parallelÖ..

Note: if you want to know more about the business of

'fake news' works see my recent book review.

This week I received an email

from a LostCousins member who had found an online

tree in which one of the individuals had, supposedly, been baptised 6 years

before he was born and married 5 times, in the space of a decade, 3 times to

the same woman, and to 2 different women on the same date. As if that wasn't

sufficient to confuse anyone, he supposedly went on to have 12 children by different

wives, 2 of whom were baptised on the same day in different parishes!

At least in that case it

should have been obvious to anyone with half a brain that there was something

inherently wrong (as was the case with the tree I wrote

about before Christmas - itís still incorrect, by the way). But often it isnít

obvious - the information may be wrong, but it's plausible.

One of the things I've

noticed about online trees is that incorrect information rarely appears in just

one tree, it sees to spread just as virally as 'fake news'. Perhaps it's

because, just as nature abhors a vacuum, family historians can't abide to have

a gap in their tree?

Actually,

there's more to it than that.

'Fake ancestry' is also persistent, because once someone has entered a name on

their tree they're not going to erase it just because they come across another

tree where there's an empty space. For example, suppose that there's a baptism

that at first sight could be the

right one, but which is discarded by a diligent family historian after further

research - perhaps because an examination of the burial register shows that the

child died as an infant.

Nobody, but nobody, is going

to delete their incorrect entry as a result of seeing

the empty space in my tree. Only if I were to see their public tree, notice

their error, then take the time to write to them to explain where they had gone

wrong would there be any chance of them putting it right - and even then, I

wouldn't bank on them taking any notice!

There's an example in my tree

of an illegitimate son born around 1825 who took his mother's surname; nothing

unusual about that, of course, but in this case the son married twice, and on

each occasion gave his father's name (which he said

was the same as his own) and occupation. His baptism canít be found - at least,

not under the surname he was known by - so everyone descended from that son who

had a public online tree showed the name of his father, but not the name of his

mother.

Eventually I did manage to

persuade all 12 of the descendants who had public Ancestry trees that they'd

got it wrong, but only by putting together a two page

document which set out all the evidence. His father is still unknown - I have a

theory, but unless one of the male descendants takes a Y-DNA test we'll

probably never know the answer.

The family tree program that

I use might be outdated and inadequate in many ways (I've been using it since

2002), but it allows me to highlight possible connections in red so that I

don't forget that confirmation is required (of course, these days that

confirmation is most likely to come from DNA evidence). But online trees donít

usually have that capability - itís all or nothing - so if I were to make my

tree public I'd first have to delete all the 'possible' entries, to avoid

misleading others.

There will always be people

who delude themselves - that's human nature. But it should be possible to make

it more difficult for them to delude others.

Perhaps one answer would be

for sites like Ancestry to offer some form of rating system for public trees? At the moment you can post a comment about a particular

entry, but unless someone looks at the same entry and realises that a

comment has been posted and reads the comment and takes it on

board they might well take the contents of the tree at face value.

Personally I won't post a public tree at Ancestry because any

subscriber will be able to see it, take the information and misuse it. I

wouldn't mind having a public tree if it was only visible to my 11,000 DNA

matches (rather than all 2.7 million subscribers), but that isn't an option

Ancestry currently offer (they should).

To their credit Ancestry do

at least take privacy seriously - there are other websites (ones you wonít find

recommended in this newsletter, naturally) which take insufficient precautions

to protect living people. And never make the mistake of assuming

that if a site is free you've got nothing to lose: remember the saying

"If you are not paying for it, you're not the customer; you're the product

being sold".

I've just purchased a one-off

12 month Premium subscription to Ordnance Survey maps.

Although you can get basic maps free of charge the Premium subscription offers

all sorts of extra features, so I couldn't resist the 30% discount offered, which

brought the price down from £25.99 to £18.19 (less than the cost of a recurring

subscription). It works on all my devices, and I can download maps to my

smartphone that I can use offline.

If you want to take up this

offer, which runs until 6th February, please follow this link

and enter the discount code WALK30

at the Checkout. The promotion is being run in connection with the ITV

programme Britain's Favourite Walks.

The price of Bitcoin is half

what it was on 11th December when I first warned readers to beware the

unexpected side-effects of a crash. Given the volatile nature of cryptocurrencies

it could well go up again or fall further - quite frankly itís a gamble, and I

donít believe in gambling (apart from a regular flutter on the National

Lottery) - but it's a good time to make sure that you aren't unnecessarily

exposed to risk.

For example, if you've just

sold a property donít hold all the money in one bank as the Financial Services

Compensation Scheme only covers the first £85,000 with any one banking group

(£170,000 for joint accounts). Since 2001 the FSCS has paid out over £26

billion in compensation to over 4.5 million people, which sounds like a good

thing until you realise that they were only being compensated for the losses

that they had suffered. You can find out more about the FSCS and what is (and

isn't) covered by the scheme here.

Note: there is now a scheme which covers

larger sums for a short period but it wouldn't cover all property sales; you can

read up on it

here.

Finally you may recall me mentioning in the last issue that 31st

January would be the 25th anniversary of the day I met my wife. I hope you were

impressed by the way I planned ahead - timing our first

meeting so that when the 25th anniversary arrived it would be marked not only

by a 'super moon', and a 'blue moon', but also by a lunar eclipse.

Valentine's Day will be our

15th wedding anniversary - but I have no super moons planned, nor any eclipses.

Nor will I be taking up the offer by

Greggs, the baker, of a 4 course meal for two - featuring sausage rolls and prosecco

- for just £15. Call me an old softie if you like, but I'm planning something

just a little more romanticÖ.

This is where any

major updates and corrections will be highlighted - if you think you've spotted

an error first reload the newsletter (press Ctrl-F5) then check again before writing to me, in case someone else has

beaten you to it......

I'll be back

again in a week's time: hopefully you'll have made good use of the free access

to the censuses, and added loads and loads of entries

to your My Ancestors page, because

finding 'lost cousins' is what itís all about!

Peter Calver

Founder,

LostCousins

© Copyright 2018

Peter Calver

†

Please do NOT copy or

republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only

granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However,

you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for

permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins

instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?