Newsletter – 29th July

2020

Good news - Ancestry changes delayed

Has your family been affected by COVID-19?

Is your maiden name the one you were given at

birth? Née

MASTERCLASS: finding birth certificates

CHALLENGE: can you break down this 'brick wall'?

Wills witnessed by video link to be legal

Society of Genealogists library re-opens on Tuesday

Important advice for libraries and family

history societies

The history of brands and companies

Pawn tickets provide clues to life a century ago

The gift that doesn't

keep on giving

The dying teenager who wanted world peace

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 23rd July) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February

2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll

get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter

available!

Good news - Ancestry changes delayed

I

discovered today that Ancestry are now quoting 'late August' as the changeover date

for their new DNA matching, which will – amongst other changes – exclude segments

of below 8cM, and this eliminate matches where only 6cM or 7cM is shared.

It's an opportunity for Ancestry users to investigate

and/or save their smallest matches by adding notes, sending messages, or adding

them to a group. Of course, a significant proportion will be spurious matches

(which is one of the reasons Ancestry plans to remove them), and there will be

many that don't have tress, or have very small trees that are of little

practical use.

The

best way to save the matches that might make a difference is to follow the two

key strategies outlined in my DNA

Masterclass, then add a note to those matches that might be of future

interest..

Has your family been affected by COVID-19?

I'm

glad to say that, to the best of my knowledge, none of my extended family have been

infected by the novel coronavirus, but it would be too much to hope that all of

the 68,000 readers of this newsletter could say the same.

Nevertheless,

we know that family historians are less likely to suffer from dementia – I wonder

whether the same might be true of coronavirus? I'd

like to think that we're more thoughtful, and hence more likely to take

precautions than the average member of the population – but is that just wishful

thinking?

Note:

I read this week that bald men are more likely to be hospitalised – thank goodness

I don’t take after my father in that respect.

Is your maiden name the one you were given at birth? Née

We

tend to use the terms 'maiden name' and 'birth name' interchangeably, but there

is a subtle difference – someone's maiden name is the name they were using

immediately prior to their first marriage, which isn’t necessary the one they

were given at birth.

One

reason for the confusion may be the way that the French word 'née' (literally

'born') is sometimes used as a synonym for 'maiden name'. Of course, most of

the time people do use the same name between birth and marriage, which is

perhaps why we can be lulled into a false sense of security – and why we're

sometimes unable to find an ancestor's birth registration. You may recall that

in the last newsletter I wrote about my relative who is recorded as Florence

Bright Harris in the birth indexes, but as Florence Bright in the marriage

indexes, her parents having married 3 years after her birth.

As

I've had a number of emails recently from members unable to find their own

relatives' birth registrations I thought it would be a good idea to update my

Masterclass on finding birth certificates…..

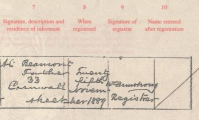

MASTERCLASS: finding birth certificates

Note:

this Masterclass focuses primarily on England & Wales but many of the principles

can be applied in other countries

It's

very frustrating when we can't find an ancestor's birth certificate - but often

the 'brick wall' only exists in our imagination. Let's

look at some of the key reasons why a certificate can't be found....

·

The forename you know your ancestor by may not be the one on the

birth certificate

Sometimes

the name(s) given at the time of baptism would differ from the name(s) given to

the registrar of births; sometimes a middle name was preferred, perhaps to

avoid confusion with another family member, often the father. Many of our

ancestors, especially females, were known by pet names: Betty, Molly, Polly, Peggy,

Fanny, Lottie, and Nell are some of the most common.

And sometimes a birth was registered without a name – not every entry in the

birth indexes that appears merely as 'Male' or 'Female' relates to a child who

died shortly after birth (though sadly many do). Although it was possible to

amend a birth register entry to reflect a change of name at baptism, most

people seem not to have bothered – which is why almost all birth certificates

have a diagonal line drawn through the box in column 10.

There can be all sorts of reasons why a different forename is used - one of my

ancestors appears on some censuses as 'Ebenezer' and on others as 'John' (which

I imagine was the name he was generally known by). In another family the

children (and there were lots of them) were all known by their middle names.

Sometimes our ancestors' memories played tricks - my great uncle was registered as plain 'Fred',

but in the 1911 Census his own father gave his name as Frederick.

·

Middle names come and go

At

the beginning of the 19th century it was rare to have a middle name, but by the

beginning of the 20th century it was unusual not to have one. Some people

invented middle names, some people dropped middle names they didn't like, and

sometimes people simply forgot what was on the birth certificate.

A relative of mine named Emerson Read, gave his son the name Emerson Cornwall

Read, presumably in homage to Emerson Cornwall, a local dignatory

– and in later records (as well as many family trees) the father retrospectively

acquired the middle name Cornwall.

·

A middle name that looks like a surname is often a useful clue

If the mother of an illegitimate child wanted the father's surname to be shown

on the child's birth certificate the only way to do this was to name the child

after the father. However that doesn't mean that everyone who has a surname as

their middle name was illegitimate – often it was a way of remembering a family

surname.

My grandfather was Harry John Buxton Calver – his mother's maiden name was

Buxton; however I don’t have any other Buxton ancestors, because my

great-grandmother was the illegitimate child of a widow.

·

The surname on the certificate may not be the one you expect

If

the parents weren't married at the time of the birth then usually (but not

always) the birth will be indexed under the mother's surname (which might or

might not be the name she acquired at birth); the main exception is where the

mother was using the father's surname and failed to disclose to the registrar

that they weren't married. In the early days of civil registration some illegitimate

births were indexed under the surnames of both parents (the examples I've seen

are from the 1840s), but this anomaly was corrected when the GRO recompiled the

indexes in the 21st century. In modern times many births are indexed under more

than one surname.

Tip: comparing the entry (or entries) in the quarterly birth indexes against

the corresponding entry in the latest GRO indexes can be instructive.

Surname spellings were not fixed in the 19th century, and some continued to

change in the 20th century (the spelling of my grandmother's surname changed between

her birth in 1894 and her marriage in 1915). Many surnames of foreign origin

changed around the time of the First World War - even the Royal Family changed

their name.

Note: don't confuse multiple index entries with multiple registrations – the

fact that an event appears more than once in an index doesn’t mean that it is

recorded more than once in the register.

·

You're looking for the wrong

father

Often

the best clue you have to the identity of your ancestor's father is the

information on his or her marriage certificate. Unfortunately

marriage certificates are often incorrect - the father's name and/or occupation

may well be wrong. This is particularly likely if your ancestor never knew his

or her father, whether as a result of early death or

illegitimacy. Not many people admit to being illegitimate on their wedding day

- and in Victorian Britain illegitimacy was frowned upon, so single mothers

often made up stories to tell their children (as well as the neighbours).

If the groom's name is the same as the name given for his father you should be

especially wary - when you're struggling to find a birth it is a strong hint that

the father isn’t who the marriage register says he is. However it might only be

the surname that's wrong - illegitimate sons were often named after their putative

father.

Whether or not the birth was legitimate young children often took the name

of the man their mother later married, so always bear in mind the possibility

that the father whose name is shown on the marriage certificate is actually a

step-father.

·

You may be looking in the wrong place

A

child's birthplace is likely to be shown correctly when he or she is living at

home (few mothers are going to forget where they were when they gave birth!),

but could well be incorrect after leaving home. Many people simply didn't know

where they were born, and assumed it was the place where they remembered

growing up.

The most accurate birthplace is the one given by the father or (especially)

the mother of the person whose birth you're trying to track down; the least

accurate is likely to be the one in the first census after they leave home. Enumerators

also made mistakes, and sometimes added extra information - for example, my great-great

grandmother was born in Lee, Kent but the 1851 Census shows her as born in Leith,

Scotland. Clearly the enumerator could have misheard 'Lee' as 'Leith', but he wouldn't have mistaken 'Kent' for 'Scotland'. Another common

error made by enumerators was to switch the birthplaces of the head of

household and his wife.

·

You may be looking in the wrong period

Ages

on censuses are often wrong, as are the ages shown on marriage certificates -

especially if there is an age gap between the parties, or one or both is below

the age of majority (21 until 1970). Sometimes people didn't know how old they

were, or knew which year they were born but bungled the subtraction; ages on

death certificates can be little more than guesses, or may be based on an

incorrect age shown on the deceased's marriage certificate. Remember too that

births could be registered up to 42 days afterwards without penalty, so many

will be recorded in the following quarter - and they could be registered up to

365 days afterwards on payment of a fine.

In my experience, where the marriage certificate shows 'of full age' it's

often an indication that in reality at least one of them was under 21 (it was

only very recently that vicars were given the power to require evidence of age

and identity). Where there was a big difference between the actual ages of the

parties the ages were often adjusted to make the gap appear smaller.

·

The birth was not registered at all

This

is the least likely situation, but it did happen occasionally - most often in

the first few years of registration, though it wasn't

until 1875 that there was a penalty for failing to register a birth. To be

certain that a birth wasn't registered you would need

to have almost as much information as would be shown on a birth certificate –

so for practical purposes it's a possibility you can safely ignore.

It is possible that a birth was registered, but that the registrar did not

forward the information to the General Register Office; there are local indexes

available for some areas (check the county Resources page at the LostCousins

Forum)..

·

The GRO indexes are wrong

This

is also quite rare, but did happen occasionally -

despite the checks that were carried out. Fortunately

the indexes that the GRO made available on their website in November 2016 were

compiled from scratch, so most indexing errors will have been eliminated

(although inevitably some new ones were introduced). Tens of thousands of

entries are known to be missing from the new indexes.

Tip: check both old and new indexes – both are available free online.

·

The GRO indexes have been mistranscribed

Transcription

errors can prevent you finding the entry you’re

looking for - so don’t confine your searching to a single website (none of them

is perfect). Bear in mind that the indexes at Ancestry for the period up to

1915 were provided by FreeBMD, so you’re likely to

get the same results from both sites, although FreeBMD

will have included some corrections that aren't reflected in the Ancestry

database. Similarly the indexes at FamilySearch were

provided by Findmypast.

How

can you overcome these problems? First and foremost

keep an open mind - be prepared to accept that any or all of the information

you already have may be wrong. This is particularly likely if you have been

unable to find your relative at home with their parents on any of the censuses.

If

you know who your ancestor's siblings were, can you find them in the birth

indexes? If not, then consider the possibility that the parents were unmarried.

Obtain

all the information that you can from censuses, certificates, baptism entries and

other sources (such as Army records). The GRO's new birth indexes show the mother's

maiden name from the start of civil registration - the contemporary indexes

only include this information from July 1911 onwards. And don’t

assume that the same information will be shown in the baptism register as in

the birth register - if the birth was registered before the baptism the forenames

could be different. (As I mentioned earlier, whilst it was possible to update

the birth entry following the baptism this rarely happened.)

Make

use of free searches - the GRO's online index of historic births is completely

free, though the search options are very limited, with

very poor fuzzy-matching. Furthermore, although maiden names are included from

1837 onwards you can’t search on maiden name only. Findmypast

offers much better search options, and you probably won’t

need a subscription because a free search provides a lot of information. Although

maiden names currently aren't recorded for every birth between 1837-1911, the fact

that you can search by maiden name alone is incredibly useful.

The

less information you can find, the more likely it is that the little you already

have is incorrect or misleading in some way. For example, if you can't find your ancestor on ANY censuses prior to his or her

marriage, you can be pretty certain that the information on the marriage

certificate and later censuses is wrong in some material way.

Don't

assume that just because something appears in an official document, it must be

right. Around half of the 19th century marriage certificates I've

seen include at least one error, and as many as half of all census entries are also

wrong in some respect (I'm not talking about transcription errors, by the way). Army records are particularly unreliable -

one of my relatives added 2 years to his age when he joined the British Army in

1880, and knocked 7 years off when he signed up for

the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1914.

Some people really were named Tom, Dick, or Harry

but over-eager record-keepers might assume that they were actually

Thomas, Richard and Henry. My grandfather was Harry, but according to

his army records he was Henry (just as well he had two other forenames - which

were recorded correctly - otherwise I might never have found him).

Consider

how and why the information you have might be wrong by working your way through

the list above - then come up with a strategy to deal with each possibility.

Sometimes it's as easy as looking up the index entry for a sibling to find out

the mother's maiden name; often discovering when the parents married is a vital

clue (but don't believe what it says on the 1911 Census - the years of marriage

shown may have been adjusted for the sake of propriety).

If

you can't find your ancestor on any census with his or her parents then you

should be particularly suspicious of the information you have - it's very

likely that some element is wrong, and it is quite conceivable that it is ALL

wrong. Tempting as it is to hold on to clues when you have so few of them,

sometimes you can only succeed by letting go, and starting from scratch.

Make

use of local BMD indexes where they exist (UKBMD links to most local indexes), and don't

forget to look for your ancestor's baptism - sometimes we forget that parents

continued to have their children baptised after Civil Registration began.

Consider the possibility that one or both of the parents

died when your ancestor was young - perhaps there will be evidence in workhouse

records. Have you looked for wills?

Could

the witnesses to your ancestor's marriage be relatives? When my great-great-great grandfather Joseph

Harrison married, one of the witnesses was a Sarah Salter - who I later discovered

(after many years of fruitless searching) was his mother. Her maiden name

wasn't Salter, by the way - nor was it Harrison - and

it was only because the Salter name stuck in my mind that I managed to knock

down the 'brick wall'. Another marriage witness with a surname I didn't

recognise proved invaluable when I was struggling with my Smith line - he

turned up as a lodger in the census, helping me to prove that I was looking at

the same family on two successive censuses, even though the names and ages of the children didn't

tally, and the father had morphed from a carpenter to a rag merchant.

Remember

that you're probably not the only one researching this

particular ancestor - and one of your cousins may already have the answers

you're seeking. So make sure that you have entered ALL

your relatives from 1881 on your My Ancestors page, as this is the

census that is most likely to link you to your 'lost cousins'.

Even

when you find the birth certificate the information might not be correct; for

example, if the child is the youngest in a large family consider the

possibility that the mother shown on the certificate was actually the child's

grandmother (see this article

for an example). When a birth was registered by one parent the name of the

other parent could only be recorded in the register if the parents were married

(or claimed to be married); as a result some births registered by the mother

named the wrong father, and (more rarely) some births registered by the father

named the wrong mother. You can see another example of a birth certificate

which names the wrong mother here.

Finally,

do you really, really need that birth certificate? Birth certificates are a

luxury that – with few exceptions - is only available for births after the

introduction of civil registration in England & Wales in 1837 (it was 1855

in Scotland, 1864 in Ireland), so you’re going to have to do most of your

research without them.

CHALLENGE: can you break

down this 'brick wall'?

There's

nothing quite like breaking down a 'brick wall' to provide us with the

inspiration and enthusiasm to knock down some more. Marilyn in Australia wrote

to me many years ago with a simple question about birth certificates, but one

thing led to another, and a couple of hours later Marilyn's 'brick wall' came

tumbling down!

How would you like to test your skill and judgment by tackling the

same 'brick wall'? All you have to do is find the GRO

index entry for the birth of Marilyn's grandfather, starting with the same

information that she gave me.

"I am having difficulty locating BMD records for my Long

family in London about 1850-1920 - my grandfather, born in 1896, came to Sydney

in 1920. I have obtained likely looking [birth] certificates from the GRO only

to find it is the wrong person.

"My grandfather was Frederick Leonard Long, born possibly on

31 Oct 1896 (or between Aug 1896 and Aug 1897). His parents were George, a

builder (born Kensington), and Emily (born Notting Hill); I'm

trying to find her maiden name.

"My grandfather's [Australian] death certificate says he was

born at Ealing and it says that on the 1901 census too.

"My grandfather's siblings were George Solomon, Elizabeth,

Lillian, John, and Rose. The family may have been Jewish. On my grandfather's

death certificate it has his father's name as Emmanuel

(but it shows George on John's death certificate) and John's death certificate

also has his forenames as John Levi. In the 1911 census Rose is Rose Annie but

I may have found her 1896 birth as Rose Edie.

"It was only in the 1901 Census that I found the whole

family... I can only find Lillian and Rose in 1911 - I can't

find either parent or the other children. It is very frustrating!"

You can solve this mystery using nothing but free websites such as

FreeBMD.

Knocking down 'brick walls' is fun and rewarding - even when it's someone else's tree - because the experience you gain will

lead to even greater achievements in the future! This challenge previously

featured in this newsletter in 2012 and 2018, but since thousands of readers wouldn’t have been members then I thought it was worth

reprinting. There are no prizes for the correct answer - and you'll

know when you've found it, so there's no need to write in.

Tip: solving other peoples' problems is much easier than solving

your own, but it isn’t because your 'brick walls' are

higher and more impenetrable – it’s because it's harder to be objective when you’re

researching your own family.

Sometimes there are people on the fringes of our family tree who

seem to be insignificant and uninteresting – until we look closer. This blog article tells

the story of one of them.

Wills witnessed by video link to be legal

This

week the Ministry of Justice announced that wills made in England & Wales

between January 2020 and January 2022 will be legally valid where the signing

of the will by the testator was witnessed over a video link (which would

[presumably include Skype, Zoom, Facetime etc). There is more information in this

article on the BBC News

website.

Society

of Genealogists library re-opens on Tuesday

From

next week the Society of Genealogists library will be opening to members only

on Tuesdays and one Saturday per month – you'll find more details here.

Although

the library is opening only for members, there's an extensive programme of online

talks that are open to all, and a few of them are free. If you haven’t used Zoom before it’s a chance to discover how easy

it is.

Note:

there are some interesting talks here on

the BALH website – you can view the slides and notes even if you’re not a

member.

Important advice for libraries and family history

societies

How

worried should we be about the risk that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19

could be transmitted through books and magazines? The REALM

project is primarily intended to support museums and libraries, but the

findings might also help family history societies to decide when and how to re-open

their libraries.

Last

week the project published results of testing that investigated how long the SARS-CoV-2

virus remained detectable on a range of paper and card items. You'll find a brief

summary of the results here,

but a detailed test report (in PDF format) here.

Further

testing is under way, and more results should be available in early August.

The history of brands and companies

It's funny what we remember from our youth – and what

we forget. The Lets

Look Again website has a wealth of information on products and the firms

that made them – fascinating!

Pawn

tickets provide clues to life a century ago

Findmypast

have released an unusual collection of transcribed records – a recently discovered

cache of pawnbroker tickets from Coventry for the years 1915-1923. Some readers

will undoubtedly find their relatives in the records – but even you have no

family connections with the area you'll find it

fascinating to look through the records. Follow this link

to find out more.

The

gift that doesn't

keep on giving

I

like giving money to good causes – it gives me pleasure. They don’t have to be charities for me to get that nice warm

feeling – there are some organisations that deserve to be supported, because

what they're doing is important, because it's helping society. But it wouldn't

be nearly as pleasurable if money disappeared from my bank account every year

without me having the option to change my mind..

I

don’t expect everyone to feel the same way, but I know that very many do - and

that's why, when a LostCousins member chooses to support my project to connect

cousins who are researching the same ancestors, there's no commitment to keep

paying. Yes, you'll get a reminder just before the

year is up, but if you ignore it no money will be taken from your credit card

or bank account. It's very different from the way that

most other sites work.

All

of which means that when a LostCousins member does decide to continue their support,

it's a conscious decision – and hopefully they get the

same warm feeling they did the first time!

I'll be 70 in a couple of months (COVID-willing),

so it was heartening to read about the lady who is retiring from running a Gloucestershire

bakery at the age of 100! You can read her amazing story in this Guardian

article.

The dying teenager who wanted world peace

When

Jeff was given two years to live he had some ambitious plans – you can read his heart-warming story in this BBC article.

I

noticed today that the World Health Organisation has picked up on something

else that I've been saying for months – they've warned

that it’s reckless behaviour by young people that has been causing the recent

spikes in infection in many European countries (it wouldn’t surprise me if the

same is true in other countries around the world). Though to be fair to the youngsters,

we oldies would probably be just as reckless if we'd

had as much to drink….

I've managed to pick several pounds of

blackberries from the hedgerows this week, and although our apples aren't nearly

ready to harvest, there are sufficient windfalls to allow me to make oodles of

stewed blackberry and apple – delicious for breakfast, served with 0% fat Greek-style

natural yoghurt. It's healthy too - although I add a very small amount of

sugar, I rely mostly on stevia for sweetening

(it's hundreds of times sweeter than sugar). The big question now is whether

the very unripe damson windfalls can be frozen, then used to make damson gin –

I guess I may just have to experiment.

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Last July we had record temperatures in Britain – this year we

might just make 30 degrees on Friday 31st. Nevertheless

our summers are still much warmer than I remember from my childhood – sometimes

it was so cold on the beach that I didn’t want to come out of the sea. Happy

days!

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2020 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter

without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional

circumstances. However,

you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for

permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins

instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?