1939

Register Special Newsletter

updated 16th

February 2016 4.30pm

What was

the 1939 Register?

How the register differs from other censuses

Why some names are crossed out &

other mysteries

Why are there more transcription errors

than usual?

How to search the 1939 Register

Pitfalls to avoid when

searching by address?

What's the difference between locked

and closed

Closed records are NOT indexed

How to work out who the hidden people

were

Who should we be looking for, and why?

What aren't we seeing?

Additional articles that you may find of interest

Extending your tree beyond 1911 using

the 1939 Register

How evacuation was planned in 1939

Storm clouds on the horizon

Qualifications desirable in an

enumerator

Operation Pied Piper

A little bit

of history

More tips

Note: if you find

this guide useful you can support my work by using the links below to go to the

Findmypast site of your choice:

What was

the 1939 Register?

Sylvanus Percival Vivian, Registrar

General for England &Wales between 1921-45, was

the driving force behind the creating of the 1939 National Register. Having

organised the 1921 and 1931 Censuses, and having written critically about the

1915 National Register he recognised that infrastructure for the 1941 Census

could be used to create a National Register, should war break out. His

preparations for the 1941 census were, therefore, intertwined with the

planning of a national registration system for the purposes of conscription,

which began at least as early as 1935.

However the National Register wasn't

created simply as a means of identifying fit young men who could be sent abroad

to die for their country - the Great War had demonstrated how important it was

to effectively marshall resources on the Home Front, and

sometimes you'll find out what people did during the war. For example, I discovered

that before my father joined up he was an ARP stretcher-bearer.

Although the 1939 National Register covered the

whole of the United Kingdom, the National Archives only holds the registers for

England & Wales - so you won't find anyone who was in Scotland, Northern Ireland, the

Isle of Man, or the Channel Islands at the time.

How the register differs from other

censuses

We're used to censuses that aspire to record

everyone in the land - but that wasn't what happened in 1939.

A key task of the enumerators who

collected the data was to issue identity cards - and for this reason military

personnel and government workers who already had ID cards are unlikely to be

recorded in Register. According to the National Archives (TNA) research

guide:

The

Register was not meant to record members of the armed forces and the records do

not feature:

- British Army barracks

- Royal Navy stations

- Royal Air Force stations

- members of the armed forces billeted in homes,

including their own homes

However,

the records do include:

- members of the armed forces on leave

- civilians on military bases

Other key differences compared to the

censuses are that relationships are not shown, middle names are rarely shown in

full, and places of birth are not listed. However, precise dates of birth are

given, and this information might well save us the cost of buying a birth

certificate, especially for our more distant relatives.

Tip:

birthdates are not always recorded correctly - I have two great-aunts

who were twins, but if you relied on what the enumerators wrote down (they were

different enumerators because both of the sisters had married before 1939) you

would think they had been born a month apart. I've no idea whether the mistake

was made by the husband or the enumerator - but it certainly wasn't the

transcriber.

Why some names are crossed out &

other mysteries

The 1939 Register was a working document

- unlike censuses, which were checked, analysed, and archived, the National

Register was updated as changes occurred. For example, if a woman married she would

normally adopt her husband's surname - and if this occurred after 29th

September 1939 a new identity card had to be issued.

Tip:

the use of identity cards didn't end when the war was over - they continued in

use until 1952.

When the National Health Service was

founded in 1948 the National Register was used as the basis of the NHS Central

Register, and this continued in to the early 1990s. As a result many name

changes were recorded as the result of marriages (and divorces) that took place

in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. There may even be some later changes - but I

haven't seen any yet.

Here's an example of a name change on

marriage:

![]()

© Crown Copyright Image reproduced by

courtesy of The National Archives, London, England and Findmypast

This tells us that May E Lawson became

Dalrymple on her first marriage (which was in 1951), and Noon on her second

marriage in 1955. She died in 1985, but the record would be open in any case as

she was born in 1904, which is more than 100 years ago.

Changes weren't made immediately -

there was usually a delay - and in the example above you can see the change of

name to Dalrymple seems not to have been recorded until early 1955, by which

time Mrs Dalrymple (nee Lawson) was well on her way to marrying again - she

married Frederick E Noon in the third quarter of that year.

This means that where a date is shown

all you can conclude is that the event must have happened prior to that date.

You are NOT seeing the date on which the person married or divorced.

Tip: information in the same colour ink and handwriting is likely to

have been entered at the same time - without this clue I might have associated

the 1955 date with the second marriage.

If there is a change of surname

recorded you can usually search using either surname. Unusually May E Noon has

only been indexed under her final surname, possibly because it's really hard to

read her original surname (Lawson). But you're more likely to see a search

result that looks like this one:

That's my mum! Note that the original surname

- the maiden surname in this case - is shown in parentheses.

Why are there more transcription errors

than usual?

If you're used to just typing in names

and seeing results pop-up you might be frustrated by the number of

transcription errors. Fortunately it's unlikely that they'll prevent you

finding the right records because there are so many different ways of searching

- and anyway, most transcription errors can be overcome by the judicious use of

wildcards. But it's important to understand just why there are more errors than usual.

First of all, there was a war on - the

enumerators don't seem to have been as careful with their handwriting as one

would have liked. The fact that they were using fountain pens probably didn't

help - there tends to be too much ink, so that some of the details disappears into a blob. And the transcribers have had to

try to interpret names that have been crossed through - as if their task wasn't

already challenging enough!

However the biggest challenge for the

transcribers was the result of privacy concerns - these records were not due to

be opened until 2040, by which time everyone recorded would have been over 100

years old. This is why we could initially only see records for people who were

born over 100 years ago, or whose death had been recorded in the register (some

other records have since been opened up for people who are known to have died).

This meant that the transcribers

weren't given an entire page to work with - instead the page was divided into

columns of data. No one transcriber would have an entire entry for an

individual, making it much more difficult to interpret what they could see.

I'm never one to criticise transcribers

because it's not a job I would want to do, even though (and, perhaps, because)

I'd be very good at it - but in this instance the challenges were greater than

usual, and we have to remember that what we see isn't what they saw.

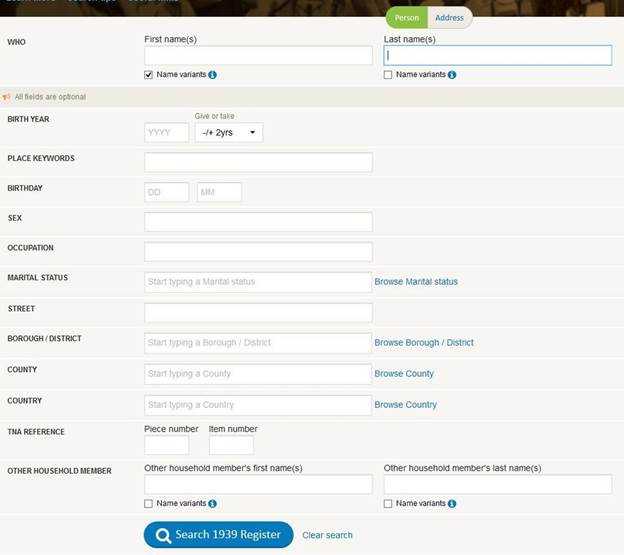

How to search the 1939 Register

Fortunately, despite the transcription

errors, the chances of picking the wrong household in 1939 are extremely low,

partly because you're much more likely to know the date of birth of a parent or

grandparent (and the chances of there being two people with exactly the same

name born on precisely the same day are pretty low), but also because before

you use any of your precious credits you'll get to see a preview that looks

something like this:

There are two ways to search - you can

search for a person, or you can search for an address. But most of the time

you'll want to search for a person, because you can include location

information a person search if you want:

As you can see, the Search page looks

very similar to the page we see when we search the 1911 Census at Findmypast,

but with the addition of the Birthday field. All of the fields are optional,

even the name - so you can start with a very broad search and narrow down by

adding more information.

Tip: less is more when it comes to

searching - the less information you enter on the Search form, the more results

you'll get! Should you get too many results you can always add more information

and try again.

Note that there are boxes on the form

for the National Archives references - the piece number, and the item number. I

suggest you record these for the households you purchase as they'll provide a

quick way of finding the record again. And who knows, perhaps one day we'll add

the 1939 Register to the list of censuses supported by LostCousins?

When you search by address there are

far fewer boxes on the form:

I suspect that the address search will

be used mainly by people who want to find out who was living in 'their' house

in 1939, or who want to find out information about their neighbours. If I have

some credits left over I'm certainly going to look at the house where I grew up

- all the neighbours must be well over 100 by now (some of them seemed it at

the time, though I expect they were younger than I am now!).

For more information about searching

please check out the Findmypast blog (you don't need to be a current subscriber).

Pitfalls to avoid when searching by

address

Searching by address sounds simple, but

there are some complicating factors that you need to be aware of:

- Postal addresses

can be a misleading guide to the Borough/District - for example, I grew up

in Chadwell Heath, Romford as far as the postman

was concerned but we were in the adjoining borough of Ilford for the

purposes of voting and rates. I didn't find this out until very recently (when

we lived there I was far too young to vote).

- There might be

more than one street in a borough with the same name - this is most likely

to be a problem with names like Station Road, or London Road.

- Some address information

was omitted when the records launched last November, and whilst this has

been rectified in many cases, the problem might persist. When you search

for a street you can view a list of all the houses that have been indexed

- even if there is a gap in the numbering it's likely that the occupants

of those properties can still be found by name.

What's the difference between locked

and closed

Locked

households are households you haven't

viewed before; unlocking a household allows you to see the open records in that

household.

Closed records exist in both locked and unlocked households

- they are records that you can't see because the person is recorded as having

been born less than 100 years ago, and their death has not been confirmed.

Closed records can usually be opened by submitting a death certificate, but you

need to know where the individual was living in 1939.

Closed records are NOT indexed

If a record is closed then you won't

find that person in the index, no matter how you search. For example, when the

register first launched in November my mother was not in the index, and because

she had been evacuated I didn't know where she was living.

Fortunately Findmypast opened an additional

2.5 million records in December, having used a sophisticated algorithm to match

death index entries against register entries - this was possible because the

death indexes from 1969 onwards include the individual's date of birth.

There are still many records which are

closed, even though the person is now deceased - unfortunately the National

Archives, who hold the registers, and have ultimate responsibility for deciding

which records can be opened, have to take a conservative approach to avoid

breaching the privacy of living people.

However if you can work out where

someone was living, and have their death certificate, it will usualy be possible to open the record. At launch about 28 million

records were open, out of 41 million - now there are 30.6 million open records, and

thousands more are opened every week.

How to work out who the hidden people

were

When you view the handwritten images you

see an entire page - other than the closed records, which are blanked out.

Usually the inhabitants of a household are listed in the same way that they

would be on a census, starting the father and continuing with the mother and

the children in descending order of age; lodgers and visitors are likely to be

at the end.

You won't always be able to see where one

household ends and the next begins, but you can easily work it out from the way

in which the entries are numbered. Remember, you know how many open and how

many closed records there are in a household from the transcription.

This means that in most cases you'll be

able to work out whose records are hidden, by combing what you can see or

deduce with your own knowledge of the family.

Tip:

in a few cases you might see a small part of a closed record - perhaps the

descender from a letter 'y', 'g', 'p', or 'j'. The position of the descender

may help to confirm that the hidden person was named 'Mary', or 'George'.

Who should we be looking for, and why?

Often the most interesting revelations

are going to come from researching people who aren't close relatives. For example,

I discovered one of my Dad's cousins living with a man who wasn't her husband,

and that solved several mysteries for me. It also indirectly enabled me to

identify several cousins who are still living - so much from just one

household!

I also found it interesting looking at neighbours,

some of whom I remembered from my childhood in the 1950s - and I discovered a lot

that I hadn't known about a family friend who my mother had worked with during

the War.

How much you learn will depend not so

much on how much you already know, but on how open you are to making new

discoveries - indeed, the more you know, the easier it will be to expand your

search outwards, to more distant relatives. What you find in the register won't

be an end in itself, but a gateway to

yet more information - once you know precisely when someone was born it's usually

easy to find their death (assuming they died between Q3 1969 and 2007), and

that makes it easier to fill in the gaps in between.

What aren't we seeing?

This rather fuzzy photo is the only

known image of the right hand side of a register - we normally only see the

left-hand page and the first column of the right-hand page. I grabbed this shot

from a video on the Findmypast blog.

I have a copy of my own record from the

NHS Central Register, from which I've been able to deduce that many, perhaps most,

of the notes relate to people moving from one NHS area to another. (I'd be

interested to hear from anyone who has also obtained a copy of their index

entry.)

We're probably not missing out on very

much by not seeing that right-hand page - frustrating as it is not to be able

to see it!

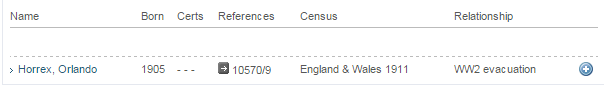

Track down evacuees

using LostCousins

The evacuation of millions of British

schoolchildren during World War 2 will have had a lasting effect, not only on

their lives, but also on the lives of the families with whom they were

billeted. Having found my mother on the 1939 Register I wondered how feasible

it would be to track down members of the family she lived with - and realised

that one way of doing this would be to use the My Ancestors page....

Whilst you can't enter people from the

1939 Register on your My Ancestors page (at least, not at the

moment), many of them will also have been recorded on the 1911 Census. I've

therefore created a new category in the Relationship or category dropdown

menu - WW2 evacuation - so that I and other members can search for relatives of

the people who looked after the evacuees in our families during the war.

Here's the first ever entry using this

new category:

I'll let you know if I get a match! In

the meantime, why not see who you can find?

Extending your tree

beyond 1911 using the 1939

Register

If your family comes from England or

Wales, and you have either a Findmypast.co.uk or Ancestry.co.uk subscription,

you'll not only have access to fully transcribed GRO birth, marriage, and death

indexes but also to the complete England & Wales 1911 Census. By combining

these two resources you'll probably find that you can add dozens of new relatives

to your family tree - without spending a penny on certificates!

Here's how I generally go about it:

(1) Where there are married couples on

the 1911 Census and the wife is of child-bearing age (typically up to 47) I

search the birth indexes for children born to the couple using the family

surname and mother's maiden name. The rarer the surnames the more confident I

can be about identifying the entries, especially if I also take into account

the choice of forenames, the timing of the births, and the districts where the

births were registered.

Tip: even if the surnames aren't

particularly rare, the surname combination might be - a search for marriages

where the bride and groom have the same surnames will help you gauge how likely

it is that the births you've found belong to your couple.

(2) I then check to see whether I can

identify marriages involving relatives who were single in 1911. This is

generally only possible when the surnames are fairly uncommon (but see below).

(3) Having identified these post-1911

marriages, or possible marriages, I look in the birth indexes for children born

to the couple using the technique described in (1) above. Sometimes the choice

of forenames will help to confirm whether or not I've found the right marriage.

(4) I next look for the deaths of the

couples whose children I've been seeking. If the precise date of birth is

included in the death indexes, as it is for later entries, this often helps to

confirm not only that I've found the right death entry, but also - in the case

of a female relative - that I've found the right marriage. Even if I don't know

exactly when my relative was born, the quarter in which the birth was

registered defines a 19 week window (remember that births can be registered up

to 6 weeks after the event). Why does this work best for female relatives?

Because they will have changed their surname on marriage, so their birth will

be registered in one name and the death in another - and there will be a

marriage that links the two.

Tip: probate calendars can also provide

useful clues - often one of the children, or the surviving spouse, will be

named as executor or administrator. You can search the calendars from 1858-1966

at Ancestry, or from 1858-1959 at Findmypast;

if you don't have access to either of these sites, or want to search for more

recent wills, you'll need to use the free Probate

Service.

(5) Now I start on the next generation,

the children who were recorded in 1911 or whose births I have been able to

identify as belonging to my tree. I look for both marriages and deaths, because

if I find the death of a female relative recorded under her maiden name, this

usually indicates that she didn't marry, and even for a male relative the place

of death might help to determine whether a marriage I've found in an unexpected

part of the country.

(6) Having identified marriages I then

look in the birth indexes for children born to those marriages - and continue

this process until either I reach the present day, or I get to a point where I

can't tell with reasonable certainty which entries relate to my relatives. Mind

you, when it comes to more recent generations there are all sorts of additional

sources of information - including social networking sites, Google, searches of

the electoral roll (see the next article) or even the phone book (not everyone

is ex-directory).

Here are some key dates to bear in mind

when searching:

2nd April 1911 - Census Day

1st July 1911 - from this date the

mother's maiden name was included in the birth indexes

1st January 1912 - the surname of the

spouse was included in the marriage indexes

1st January 1966 - from this date the

first two forenames are shown in full in the birth indexes

1st April 1969 - the precise date of

birth was included in the death indexes and the first two forenames were shown

in full

During the 20th century middle names

are more consistent than they were in the 19th century - there is less of a

tendency for them to appear or disappear between birth, marriage, and death.

Unfortunately, for more than half a century after 1910 only the first forename

was shown in full in the birth and death indexes, and the marriage indexes only

show one forename for the whole period after 1910 - so a perfect match on the

second forename is only possible if the relative was born before 1911 and died

after March 1969.

What can you hope to achieve by

following the techniques I've described? In my case I was able to extend some

lines forward by as many as four generations, although three is more typical.

In the process I added hundreds of 20th century relatives to my family tree,

the majority of whom were still living.

Since the 1939 Register was

released I've been able to extend my tree further by confirming that many of

the marriages I'd noted as possible marriages did indeed involve my relatives

(the fact that precise birthdates are given is a really big help).

One of the best things about the 1939

Register is the way that it continued to be used after the War - and so the

surnames of many women were updated to reflect marriages (and divorces) that

took place in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s or even later. This makes the 1939

Register more useful than a static census, and since it was released I've added

dozens more relatives to my tree, most of whom must

still be living.

Note: there will often be other resources that you can draw upon, including parish registers (some online collections extended beyond 1911), newspaper announcements (iannounce

is good for recent events, the British Newspaper Archive - also at Findmypast - for early 20th century events). Burials recorded at Deceased Online are another great source (for example, there may be other family members in the same grave). Historic Phone Directories up to 1984 are online at Ancestry. Ancestry and Findmypast each have historic Electoral Rolls - Findmypast covers much of the country, but Ancestry is best for London.How evacuation was

planned in 1939

In 1939 each area of the country was

assigned one of three roles:

- Evacuation

- Reception

- Neutral

I was fortunate to find a document online at the HistPop website which details which areas came into

which category, and I suspect many of you will find it very interesting to look

up the areas where your family lived. It's about 12 pages long - use the Previous

Page and Next Page links at the bottom to navigate;

my understanding is that areas not specifically mentioned were Reception areas.

Of course, trying to predict which

parts of the country would be safe from the Luftwaffe wasn't a precise science

- one member wrote to tell me that his family moved "out of the frying pan

into the fire" when they relocated!

When Britain declared war on Germany in

September 1939 it was a sad day, but it wasn't a surprise. You probably

remember that when I wrote about Operation Pied Piper last weekend I mentioned

that evacuation forms were circulated to parents as early as May 1939, and it

turns out that plans for the issue of identity cards were being formulated as

early as 1st December 1938, when the General Register Office circulated a memorandum to Registrars of Births and

deaths about:

"proceeding immediately

with certain of the preparations for the 1941 Census, as a means of providing

for the institution of a National Register at very short notice, should a

national emergency arise."

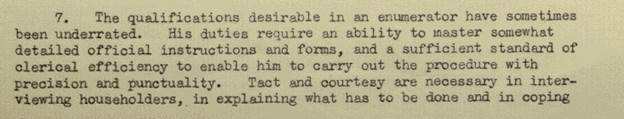

Qualifications desirable in an

enumerator

When a further memorandum went out from

the General Register Office on 6th January 1939 it stated that:

When you've seen as many pages from the

National Register as I have, you'll know that the enumerators didn't always

live up to those high standards - even handwriting that appears neat can be

hard to read if the letters are written inconsistently, or confusingly.

The fact that subsequent amendments to

surnames were made in block capitals suggests that even at the time the

handwriting was causing problems.

With the threat of war looming, the

British Government prepared plans for mass evacuation. During WW1 Germany had

bombed London and other targets using Zeppelin airships (you can read more

about it here), but now the enemy had modern bombers

(over 1000 were operational by September 1939), and the bombing of Guernica in 1937, during the Spanish

Civil War, had demonstrated the devastation that could be wrought. Preparations

started long before the war: this form headed Government Evacuation Scheme is

dated May 1939 - note that mothers were asked if they wanted to go with their

children.

Operation Pied Piper went into action

on 1st September 1939, two days before Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime

Minister made his momentous radio broadcast to the nation:

"This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin

handed the German Government a final Note stating that, unless we heard from

them by 11 o'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops

from Poland, a state of war would exist between

us.

"I have to tell you now that no such

undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with

Germany."

Children had assembled in school playgrounds on the

morning of 1st September, each with a luggage tag attached to their coat, and

carrying bare necessities: their gas mask, underwear, pyjamas or nightdress,

plimsolls, toothbrush, comb, soap, and a face flannel. Over half a million

children were evacuated from London alone during September, and my mother -

then 13 years old - appears to have been one of them, because on Registration

Day (29th September) she wasn't at home with my grandparents.

Children had assembled in school playgrounds on the

morning of 1st September, each with a luggage tag attached to their coat, and

carrying bare necessities: their gas mask, underwear, pyjamas or nightdress,

plimsolls, toothbrush, comb, soap, and a face flannel. Over half a million

children were evacuated from London alone during September, and my mother -

then 13 years old - appears to have been one of them, because on Registration

Day (29th September) she wasn't at home with my grandparents.

Over the course of just three days

around 1.5 million mothers and children were sent from towns and cities into

the countryside, mostly by train - you might this Southern Railways poster interesting. However, because

bombing raids on cities didn't materialise in the first few months of the war,

many children went back home - over half had returned by January 1940, despite

Government warnings (I believe my mother was one of

them).

There were further waves of evacuation

during 1940, and my mother's school was evacuated toFinnamore Wood

Camp, Marlow, Buckinghamshire on 22nd April - you can see a

photo here which shows some of the schoolgirls.

My mother wasn't amongst them, however - my grandmother wouldn't allow her to

leave home again - and so my mother left school and spent the duration

supporting the war effort, working at the nearby Ship Carbon factory, which

made carbon rods for cinema projectors and searchlights.

A smaller number of children were

evacuated overseas, a story told in the book Out of Harm's Way, written by an evacuee -

but this programme came to end when the SS City of Benares was sunk in

September 1940, killing most of the children on board. However

some children were evacuated privately even after this incident.

In 1939 the country was divided into

more than 1400 administrative areas, each of which was assigned a three letter

code, such as CJL for Bromley in Kent and ZDJ for Portmadoc in Caernarvonshire (larger areas may have

had more than one code, in which case the code in the table is the first in the

block). When you find one of your relatives you'll see that a fourth letter has

been appended to the end - this specifies the enumeration district.

You will find a table of all the codes

and areas here.

A little bit

of history

When, in February 2007, I asked to

inspect the 1939 Register under the Freedom of Information Act I was rebuffed -

it's covered by the 1920 Census Act, they claimed. Absolute rubbish, but for a

while they got away with it.

Eventually, thanks to the efforts of

Guy Etchells and others, it was agreed to provide

information from the Register, subject to a fee of £42 per household (which

wasn't refundable under any circumstances). Then, in March 2014, Findmypast

announced that they had signed a deal with the National Archives which would

see the register becoming available online within 2 years.

More tips (some duplicate tips mentioned above)

· Use the Advanced search - it'll save you time

· Middle names are not shown, only initials (even

though it would appear that full middle names were recorded on the original

household schedules)

· Closed records are NOT indexed, so will not show up

in searches, nor will people who were in army barracks or similar institutions

· If you don't have a subscription you'll be asked if you want to 'unlock' the record

- this is the point at which the 60 credits are deducted; in return you get to

see a transcription of the 'open' entries in the household, and the image of

the register page

· The register pages are like the enumerators'

summaries that we see for the censuses up to 1901 - the entries have been

copied from the schedules completed by the householders, so we don't get to see

our ancestors' handwriting (on the other hand we see a whole page of entries,

up to 44 - but on average 14 of these will be closed at launch)

· The references displayed are in this format

Ref: RG101/1100C/019/36 Letter Code: CCVZ

where RG101 is the National Archives reference for the

1939 Register (this doesn't change)

1100C is the piece number

019 is the item number (it identifies a specific page but I

couldn't see the number in the image)

36 is the line number on the page - again it's not shown, but you

can count down

The Letter Code refers to the area - there's a guide to these codes in

the TNA blog, and a list of codes here

· You're also given the Schedule Number and Schedule

Sub-Number but can't search using this information; people in the same

household have the same Schedule Number (the Sub-Number is the line on the

Schedule, usually 1,2,3,4 etc)

· Make a note of the references - they'll enable you

to find the page again instantly (and you never know, one day we might use

these records at LostCousins!)

· National Registration Day was 29th September 1939,

but someone who is listed may not have arrived until the next day (assuming

they were not registered elsewhere)

· 'Unpaid DD' means 'Unpaid

domestic duties'

· To open a closed record by uploading a death certificate

start from the household transcription, but DON'T click Check if

you can open a closed entry. Instead click Update the record,

and choose Ask us to

open a closed record from the drop down menu. You must have a 12 month

Britain or World subscription to be able to do this.

· Take a look at this blog entry,

posted by Findmypast on 3rd November

Unexpected bonuses

· The register was a working document - though it was

created in 1939 it was amended and annotated as people moved, married, and

died; most of the annotations are on the right-hand page, where we can't see

them, but there are some on the left-hand page (see below for a guide to

abbreviations)

· Sometimes a woman's surname will have been crossed

out and another surname written in - this is usually a name change on marriage;

in the Search results the surname in 1939 will appear in brackets;

there are more than two surnames all but the most recent will be in

brackets

· In these cases you can search on any of the surname

(you don't have to tick the surname variants box), but the entry you want

probably won't be at the top of

the search results because of the way they are sorted

· If you're very lucky you may find someone whose

name changed on adoption (they would have had to be adopted after the creation

of the register, otherwise you wouldn't see the birth name)

· On the right hand side of the register you can sometimes see a note such

as 'ARP warden'

· You might see an alias recorded, for example one 'Harry' was noted as 'o/w Henry'

· Occasionally the date of death is recorded on the right hand

page - check it against the GRO indexes to make sure

· My aunt's year of birth was erroneously transcribed

(by the enumerator) as '76' rather than '16' which meant her record was open

when it should have been closed - were she still with us she would have been

absolutely delighted!

· Sometimes you'll see a note such as "See page

14"; in this case there will usually be an arrow to the left or right of

the image - click the arrow to see the other record

· When there isn't an arrow you are likely to find

the individual listed twice in the Search results; if so you'll have to pay to

access the second page (but it might be worth asking for a refund)

· If your relative was in an institution you should be able to see all of

the pages relating to that institution - click the left and right arrows

Interpreting

the notation

The modern day NHS computer system

still uses some of the forms - you can find detailed guidance here, but most of it isn't relevant and these

notes probably tell you all you need to know:

· Dates shown are usually not the date of the event,

but seem to be the date of the update (or possibly the date on the form that

triggered the update)

· CR283 is a form that is used when there is a Change

of Surname, Forename, or Date of Birth (most changes will be surname changes,

of course)

· NEL probably stands for "North East

London"; many other three letter codes can be interpreted by referring to

this table

· IC or I/C almost certainly stands for Identity Card

· See Con Sheet means "see continuation

sheet" (unfortunately the continuation sheets don't seem to be available)