Newsletter

- 27th February 2015

Northamptonshire

registers online NEW

Royal

Navy records at Ancestry

7

million articles from Irish newspapers

Australian

census under threat

Aunt

Betty was a WW1 spy - or was she?

Writing

about your family's history

Using Y-DNA

to verify your research

Verifying

your research using autosomal DNA

Analysing

old family photographs

Church

graffiti reveals plague victims

Did

rats really cause the Black Death?

How long

does your PC take to boot?

The LostCousins newsletter is usually published

fortnightly. To access the previous newsletter (dated 13th February)

click here, for an index to articles from 2009-10

click here, for a list of articles from 2011

click here and for a list of articles from

2012-14 click here. Or use the customised Google search below

(that's what I do):

Whenever possible links are included to the

websites or articles mentioned in the newsletter (they are highlighted in blue or purple and underlined, so you can't miss them). If one of

the links doesn't work this normally indicates that you're using adblocking software - you need to make the LostCousins site

an exception (or else use a different browser, such as Chrome).

To go to the main LostCousins website click the

logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not already a member, do join -

it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you whenever there's a new edition

of this newsletter available!

Northamptonshire

registers online NEW

Ancestry.co.uk have

made available online indexed register images for Northamptonshire which

include 781,000 baptisms

and 478,000 burials

covering the period 1813-1912.

Tip:

you won't find these records listed under 'Recently added and updated

collections' because the release date has been erroneously entered as 2014,

rather than 2015.

Royal Navy records at

Ancestry

Ancestry have also added nearly 388,000

records of Royal

Navy Seamen from ADM188 at the National Archives; the records include seamen

who began their service between 1900-18 and list the ships they served on as

well as some personal details

Tip:

if you don't have an Ancestry subscription the same Royal Navy records appear

to be available through Findmypast

Other Royal Navy records at Ancestry

include:

Naval

Officer and Rating Service Records, 1802-1919

Naval

Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1972

7 million articles

from Irish newspapers

With the addition of 1.6 million new

articles since January, there are now over 7 million articles from 65 Irish

publications in the newspaper collection at Findmypast.ie

(you can also access them from other Findmypast sites if you have a World

subscription).

Australian census under

threat

The Australian government are

considering scrapping their census after 2016 according to this article.

Note:

until very recently Australian censuses were destroyed once the statistical information

had been extracted.

Aunt Betty was a WW1

spy.... or was she?

Last Sunday the Independent published

the tale of Ethel Raine, known to her family as Aunt

Betty. The headline reads " Ethel Raine: The untold story of a woman who spied for Britain

during the Great War", and the information in the article seems to have

been gathered by her grandson.

But is the story true? As anyone who has

written to me asking for advice will know, I don't take things at face value -

and when I attempted to verify some of the details in the article I ran into a

brick wall. For example, the newspaper article says that Ethel was 27 years old

in 1915, which means she would have been born in 1887/88. But it also says that

she was the daughter of Sir Walter Raine, who was MP

for Sunderland after the Great War.

Walter Raine,

who was knighted in 1927 according to his obituary

in the Glasgow Herald of 20th

December 1938, was indeed MP for Sunderland between 1922-29,

but as he was only 64 years old when he died it seems extremely unlikely that

he was Ethel's father. He didn't marry until 1899, and would have been no more

than 14 when Ethel was born.

I then found an earlier article,

published on the website of the Hull Daily

Mail on 18th December. This doesn't mention Sir Walter Raine

at all, but says that she was born in Sunderland and that she was 86 years old

when she died in 1974. This suggests that she is the Ethel Stonehouse

whose death was registered in Holderness registration district in the 1st

quarter of 1974, and whose birth date is given in the death index as 3rd June

1888.

There is an Ethel Raine

who was born in Sunderland in 1888, and her birth was registered in the second

quarter of 1888. My guess is that she's the Ethel Raine

aged 12 who is living with her father William, an Inland Revenue clerk, on the

1901 Census, but it is only a guess - maybe someone reading this can pick up

the baton and find out more? (She appears on a few Ancestry

trees, but they give her year of birth as 1895.)

Oh, and by the way - the Hull Daily Mail tells us that Edith's

job was "to supervise soldiers’ leave throughout the war". Hardly the

job of a spy - it sounds to me as if she was more Miss Moneypenny

than Pussy Galore.

Tip:

don't believe anything you read, unless you have verified it yourself!

Writing about your

family's history

These days most family historians have

computers, word processing programs, and printers - some of us even have our

own websites. This means it's easier than ever before to write about our family

and share our stories with others.

But what sort of story are you going to write about your ancestors and their families - will

it be strictly limited to documented facts, or will you enliven it by adding

stories handed down within the family, and by making reasonable assumptions

about the reasons for the decisions that your antecedents made?

Few of us are going to spend hundreds of

hours writing about our family history unless there is an expectation that our

living relatives will want to read it. Indeed, some you may feel that your

family stories are so interesting that they deserve a wider audience - over the

years I've published some wonderful articles written by members. For the

general reader these help to breathe life into a subject that they might

consider rather dull (or at least, would have done before Who Do You Think You Are? launched in October 2004).

But how will family historians of the

future interpret what you've written? Will they know that you've embellished

the facts in order to make the story more interesting and, if so, how are they

supposed to tell proven facts from plausible fiction.

Are you in danger of turning family

history into family mystery?

One of the topics we’re going to be

discussing in Portugal next month is the Genealogical

Proof Standard. There are five key elements:

- A

reasonably exhaustive search has been conducted.

- Each

statement of fact has a complete and accurate source citation.

- The

evidence is reliable, and has been skilfully correlated and interpreted.

- Any

contradictory evidence has been resolved.

- The

conclusion has been soundly reasoned.

I'm not going to prejudge the outcome of

the debate, which I'll be reporting on in a future newsletter, but I'd like to draw

your attention to the final two elements, as in judging the entries for the challenge

in the last newsletter I noticed that quite a few of the entrants didn't even

mention evidence that contradicted their conclusion. To be fair, I didn't ask

them to do this, and in most cases they had the right answer - but it got me

thinking about the more general issue.

The fact is, it's very tempting to

ignore contradictory evidence - as anyone who listens to politicians or reads

about miscarriages of justice will know - but since we

as family historians are cheating ourselves when we twist the evidence to fit a

particular version of events it seems a pretty futile exercise. Perhaps there's

a conflict between the psychological need to finish what we're doing (so that

we can move onto something else), and the imperative for family historians to

keep an open mind until the evidence eventually becomes so overwhelming that

there can be only one answer.

When you're trying to explain something

that your ancestors did or didn't do, don't stop at the first plausible

explanation. It might be right, but it might not, and if you gamble everything

on your guess being right you could lose the lot (for example, if you end up

tracing the wrong line).

The feedback I've had from members who

took up the challenge in my last newsletter has been very positive - for

example, Leonie wrote that "I have found this journey really entertaining",

Sally commented "Great fun", and Alison said "What a great

challenge!".

To encourage more of you to exercise

your undoubted skills on a real humdinger of a challenge I'm adding some extra

prizes. Mary has already won the prize for the first correct entry, but I also

offered a free LostCousins subscription for the person who submitted the best

entry.

I've now decided that instead of a

single prize for the best entry I'm going to give out up to TEN subscriptions.

Five of these will go to current LostCousins members

who submit the best entries, but five will be reserved for new members (ie members who join on or after the date of this

newsletter), so you might want to publicise the challenge to the family history

societies, online forums, and Facebook groups to which you belong.

It's a great opportunity to prove that

you've "got what it takes" - not so much to me, but to yourself! All

the information you need can be found here,

and you've got until Monday 16th March to send in your entry.

Using Y-DNA to verify your

research

DNA testing isn't something you should

only consider when you want to knock down 'brick walls' - it can also provide

you with a means of verifying that your research is correct.

In the simplest case you (or a male

relative) might take a Y-DNA test. You would expect that at least some of the

matches you get are with people who have the same surname (since Y-DNA is

passed down the male line), and most of the time that's what will happen.

But what if the most common surname on

your list of matches is a different one entirely? This could indicate a

Non-Paternal Event (NPE), ie one of the ancestors in

your direct paternal line was adopted, or illegitimate, or the product of an

extra-marital liaison (it's rather like the recent discovery that King Richard

III's Y-DNA didn't match that of the descendants of John of Gaunt.). This

doesn't mean that the research you've carried out is wrong, because the NPE

could have been many generations ago, but it should set alarm bells ringing.

At this point you should consider asking

a distant cousin who bears the same surname to test. If their Y-DNA is a close

match for yours, this confirms that the NPE did not occur in the generations since

your nearest common ancestor. It also confirms that your research back to that

point is correct - so the more distant the cousin the better.

Of course, you might instead discover

that your distant cousin's Y-DNA isn't

a match for your own. In this case, the next thing to ask is whether he is

getting matches with people who bear his surname - if so,

this suggests that there is a NPE in your

line of descent from the supposed common ancestor, or that there is an error in

your research back to that point.

Note:

my cousins and I tested with Family Tree

DNA, who have the world's largest database of

genealogical Y-DNA results.

Verifying your research

using autosomal DNA

When I wrote about autosomal DNA testing

last June I described it as the 'lucky dip' of DNA tests - because you simply

can't predict what you'll discover.

Autosomal DNA (atDNA)

is inherited from both parents, who inherited it from their parents and so on.

At each generation roughly half of the DNA passed on comes from each parent,

and so if you look back 10 generations just under 0.1% (on average) of your DNA

has been inherited from each of your 1024 8G grandparents.

However, in practice you won't have

received inherited DNA from every ancestor, and the further you go back the

less likely it is that you've inherited any detectable DNA from a given

ancestor.

But that doesn't mean that atDNA tests are useless - far from it. The pattern of

inheritance means that when we get a match the common ancestor could be in any

part of our tree, not just in our direct paternal line, and whilst it might not

be possible to look back many generations, most of us have unresolved puzzles within

the last 5 or 6 generations (I certainly do!).

When you get a match with a distant

cousin you already know it helps to verify the research that you've both

carried out - as far back as your nearest common ancestor(s). However the fact that

you don't get a match with a distant cousin doesn't have the same negative

connotations, because you will have inherited different parts of your DNA from

the ancestor(s) your share, and it's quite feasible

that there won't be any overlap.

Of course, when you test your atDNA you'll also get matches with cousins you don't know -

but that's a story for another day.

Note:

I tested with Family

Tree DNA because their database has more results from Europe than any other

testing company - and if you live in the UK their Family Finder test is by far

the cheapest option.

Analysing old family photographs

I mentioned earlier this month that

Jacqueline was very pleased with the analysis carried out by 'photo detective' Jayne Shrimpton,

and in view of the positive response from readers I asked Jacqueline to write

an article about her experience:

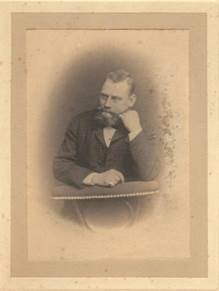

I

have long considered sending my photos to an expert but never got round to it

and a recent special offer by Findmypast to its annual subscribers of 15% off

Jayne's service finally galvanised me into action. I already knew the photos to

be of my 2x great grandparents, Henry James Sweeting, born in Bethnal Green,

East London, in 1836 and his second wife, Elizabeth Donne, born in Greenhithe, Kent in 1835. They married in 1860 in

Westminster; Elizabeth died in 1911 and Henry in 1930. Although they look like

a pair, they are clearly not, since the vignette style 3/4 poses show Elizabeth

standing facing slightly to her right and Henry sitting astride a chair with

his arms resting on the back, also facing slightly right. Henry rose from

poverty in a silversmith's family to become a successful business man in Camberwell

and the photos appear to be of them in early middle age. Although they are in

identical high quality mounts, there is no photographer's identification on

them except that they both have the same number written in pencil on the backs.

Over the years, I have cut out experts' photo datings

from family history magazines and assembled a fairly formidable

"encyclopaedia", and bought several books of dating historical and

family photos, but I was not satisfied with my conclusions; I also took them in

to the /Gallery of English Costume/ in Manchester for the opinion of a curator.

I was lucky to catch a young man who off the top of his head, said they were

probably from the 1870s. However, I was still puzzled by the dates of the two

because Elizabeth's hat seemed to be of a short lived style from the early to

mid '80s, and I also wondered why they were taken at all since they were high

quality studies of a married couple but not taken together.

I

have long considered sending my photos to an expert but never got round to it

and a recent special offer by Findmypast to its annual subscribers of 15% off

Jayne's service finally galvanised me into action. I already knew the photos to

be of my 2x great grandparents, Henry James Sweeting, born in Bethnal Green,

East London, in 1836 and his second wife, Elizabeth Donne, born in Greenhithe, Kent in 1835. They married in 1860 in

Westminster; Elizabeth died in 1911 and Henry in 1930. Although they look like

a pair, they are clearly not, since the vignette style 3/4 poses show Elizabeth

standing facing slightly to her right and Henry sitting astride a chair with

his arms resting on the back, also facing slightly right. Henry rose from

poverty in a silversmith's family to become a successful business man in Camberwell

and the photos appear to be of them in early middle age. Although they are in

identical high quality mounts, there is no photographer's identification on

them except that they both have the same number written in pencil on the backs.

Over the years, I have cut out experts' photo datings

from family history magazines and assembled a fairly formidable

"encyclopaedia", and bought several books of dating historical and

family photos, but I was not satisfied with my conclusions; I also took them in

to the /Gallery of English Costume/ in Manchester for the opinion of a curator.

I was lucky to catch a young man who off the top of his head, said they were

probably from the 1870s. However, I was still puzzled by the dates of the two

because Elizabeth's hat seemed to be of a short lived style from the early to

mid '80s, and I also wondered why they were taken at all since they were high

quality studies of a married couple but not taken together.

Well, it seemed to be easy for Jayne who almost by return of email sent me a side and a half of A4. She opened the report by looking at the photos together. She said "Your large photographic prints on substantial mounts were not a common format used for original photographs, but they do exemplify the manner in which photographic reprints and enlargements were commonly presented."

She went on to say that photos could be copied and enlarged and mounted in such a way as to form "significant portraits suitable for displaying" in frames or for hanging. "Apart from the generous dimensions of the mounts, one sign of copies...was that often the portraits were given an artistic vignette treatment," the central image fading out around the edges.

She

went on to explain why this might happen. Sometimes a pair of reprints

"would be ordered because one or both of the subjects had died and the new

pictures became special 'memorial portraits', by which family members could

remember the deceased." The style of the card mounts suggested the early

c20th. They could have been made following Elizabeth's death in 1911 by Henry

or one of their children. She said that in such a case "the original

photographs ... did not necessarily have to be a matching pair...Sometimes the 'best'

surviving likenesses of a man and a woman might be used." So that was a

very plausible reason for the "why?"

She

went on to explain why this might happen. Sometimes a pair of reprints

"would be ordered because one or both of the subjects had died and the new

pictures became special 'memorial portraits', by which family members could

remember the deceased." The style of the card mounts suggested the early

c20th. They could have been made following Elizabeth's death in 1911 by Henry

or one of their children. She said that in such a case "the original

photographs ... did not necessarily have to be a matching pair...Sometimes the 'best'

surviving likenesses of a man and a woman might be used." So that was a

very plausible reason for the "why?"

She then went on to examine the photos separately; they may have been, but were not necessarily, taken at the same studio at a similar, but not the same time. Very likely; they lived in Camberwell, not far from Peckham Rye for some 20 odd years once Henry began to make his way. Jayne said that "men's appearance can be hard to date very closely from fashion clues" since their suits "were essentially rather uniform" but she looked at the style of the pose, his beard, and the collar of his lounge jacket to come up with a date of c 1876-1884.

"When a married person visited the studio alone for a single portrait, usually they were celebrating a personal occasion, such as a landmark birthday." She judged him to "be aged about 40 or thereabouts" in the photo. Henry was 40 in 1876. Elizabeth's pose is typical of the 1870s and '80s, as is the seat used as a studio prop. Her daytime costume was of a style called "/cuirass/ ... developed in 1874/5, continuing in an increasingly extreme form into the early 1880s. This would suggest a date range of 1875-79" for the original. As for the hat which fooled me as to the date of the original, it goes to show that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing! It was not a hat at all but "the ornate day cap of a married woman, still considered an important accessory for mature women in the mid-Victorian era." Jayne concluded that she too was probably celebrating a personal occasion and she too looked to be "aged 40 or so". This fits in well with Jayne's dating of 1875-9 since Elizabeth was 40 in 1875 - "her milestone birthday." These were the probable answers to "when?"

This report answered all my questions in a very satisfactory way; no amount of poring over my personal and online images could have done it for me. And it all cost just a little more than a BMD certificate, with the benefit of a very friendly "after-sales service".

You'll find full details of Jaynes Shrimpton's services and pricing if you follow this link.

Church graffiti reveals

plague victims

This BBC News article

tells how names scratched on a church wall identifies three Cambridgeshire

sisters who are thought to have perished in the plague of 1515 (it predates the

introduction of parish registers in 1538).

The inscription was found by volunteers

from the Norfolk and Suffolk Medieval Graffiti Survey (goodness knows what they

were doing in Cambridgeshire). I wonder what else we might discover from graffiti?

Did rats really cause

the Black Death?

Another BBC article suggests

that the spread of plague across Europe was caused not by black rats, as

previously assumed, but by gerbils from Asia. Analysis of tree rings has shown

that there is no relationship between the weather in Europe and the timing of

outbreaks - which would have been expected if rats were the primary cause. The

next step is to analyse plague DNA recovered from the remains of victims.

As a result of famine and plague the

population of England fell by between one-third and one-half during the

mid-14th century, and didn't recover until the 16th century.

I often get emails from members asking

how they ought to organise their research, and as I haven't written about this

topic since 2010, I thought I'd briefly summarise what I do:

I have two parallel sets of records,

written records and digital records. Any unique documents that come into my

possession, for example photographs or original certificates, are scanned in -

just in case something happens to the original. When I find a household on any

of the censuses I save the image on my hard drive, then

load it into Irfanview where I trim off the margins and adjust the brightness

and contrast before printing it out.

The folders on my hard drive closely

emulate the files in my filing cabinet - I have a folder for each of my

ancestral lines (ie one for each surname borne by a

direct ancestor), and within that main folder I have subfolders for the

collateral lines that I've researched in the most detail.

I'm not suggesting that what I do is the

best way to organise your records, and it's certainly not the only way - but it

has worked well for me for well over a decade, so it might work for you too.

More than 400 years ago Shakespeare

questioned whether names are important, but I think it's fair to say that they

still are, especially if you're a horse called Brian.

Brian was training to become a police

horse, but a police spokeswoman said the mounted section tended to give their

horses "god or war-related names, such as Odin, Thor or Hercules" -

this BBC News story

tells of the outcry that ensued.

When we're researching our family

history we tend to assume that the names by which we know our ancestors are the

ones that we'll find in official records, in parish registers, and on censuses

- but usually we'll be wrong.

Meet Jefferson Tayte

How can you meet someone who only exists

in the pages of Steve Robinson's genealogical mysteries - it sounds impossible,

doesn't it?

In fact the answer is simple - you need

to be in the story! And you can do just that if you win the charity auction that's

currently taking place on eBay (you'll find it here).

The auction ends on 8th March, so don't delay - I've already placed my bid!

It's a very good cause - the proceeds go to CLIC Sargent, the charity that

helps children with cancer (it was one of the charities I chose to benefit from

donations when my father died).

Note:

although I've never featured in a novel myself (yet) the fictional genealogist

Morton Farrier did use the LostCousins website to crack his last case - see this

article

from December.

I've had a really bad cold for the past

10 days, so I've used this as an opportunity to catch up on my reading and do

some of the accounting and filing that I'd normally leave (and leave, and

leave). The one book I was able to read from beginning to end was The

Surnames Handbook, by Debbie Kennett (who will be telling us all about

DNA in Portugal next month).

You might think, from the name, that

it's a dictionary of surnames - but it's actually much more useful than that. Debbie

reviews the existing literature on surname origins (she certainly doesn't hold back

from criticism - or praise), then tackles the issues that we need to consider

if we are going to research the bearers of our own surname, even if it doesn't

blossom into a full one-name study. For example, she surveys the pre-1600 resources

that are available to us - and points out that there are only two English

families which can reliably trace their descent in the male line before the

Norman Conquest.

I came away realising that there were

parts of my tree which would benefit from a different approach - where there

are rare surnames which may have a single origin I could start from the

earliest recorded instances and work forwards, rather than always working

backwards.

For example, the earliest recorded

English bearer of the surname Vandepere was a

carpenter called Launcelot, who worked in Canterbury

in the mid-16th century (and seems to have been a freeman of that city). I

haven't been able to make a connection between him, and my earliest Vandepere ancestor, who lived a century later, but by

working forwards from Launcelot as well as backwards

from my John I'm going to have a much greater chance of success.

The

Surnames Handbook is available as

a paperback or as a Kindle book - and it's absolutely crammed with information,

links, references, and useful advice. I wouldn't describe it as light reading,

but the best books on family history never are: buy it, read it, and keep it

handy!

How long does your PC take

to boot?

There was a time when I'd have time to

make a cup of coffee while my PC booted up, but these days I barely have time

to blink. Since I replaced my hard drive with a solid-state drive it boots up

in about 20 seconds - and I now use the original hard drive for backups.

By the way, it's not simply quicker to

start up - everything seems to be faster - and whilst solid-state drives are

more expensive to buy, because they don't have moving parts they're said to be more

reliable and longer-lasting.

Right now you can buy the same SSD for about

the same as I paid at Amazon

or, for a little bit more, direct from the manufacturer.

It comes with an OEM version

of Acronis True Image to clone your old hard drive to the SSD, and this works

even if the drives are different capacities. In my case I went from a 1TB hard

drive to a 512GB SSD, which wasn't a problem because I'd only used 386GB.

Just one tip this time - go back to the

beginning of the newsletter and glance through the articles you skipped the

first time!

This week I confirmed something that I'd

suspected for some time - that some readers of this newsletter cherry-pick the

articles, not realising that there are often hidden nuggets (the titles aren't

always an accurate guide to the contents). And please don't make the mistake of

assuming you know it all, because none of us does - not you, and certainly not

me.

This is where I'll post any last minute

additions.

Next time you hear from me I'll probably

be at Genealogy in the Sunshine -

wish me luck!

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2015 Peter Calver

You

MAY link to this newsletter or email a link to your friends and relatives

without asking for permission in advance - but why not invite them to join

instead?